A Best-Kept Secret – Herding with Pumik

I am often asked about our journey of becoming artisan farmers in upstate New York. To be frank, it has not been a straight shot like one would naturally take from point “A” to point “B.” We Hungarians somehow always select a path that appears shorter, even though it leads through the proverbial forest.

When deciphering the trajectory of my voyage, it might be confusing to know that I was born, raised, and for 24 years, lived in the very center of Budapest, across from the iconic “gare de l’ouest” or Western railway station, built by the Eiffel company. The biggest plot of land I’ve ever owned before arriving in the US was a potted geranium that I removed from my neighbor, Mrs. Silberblatt’s, window in my apartment building after she was taken to the hospital for an emergency gallbladder surgery.

Unfortunately, she never made it out of the hospital and I admit that I never put the flower back by her window. After all, I thought I was rescuing the poor plant. After the funeral, the Silberblatt family had an estate sale, but they never noticed the missing plant. They sold the old lady’s apartment, and so I got away with my “land grab.” A couple of years later, I learned that Mrs. Silberblatt was misdiagnosed and her gallbladder was actually fine. By then, I no longer had the geranium because the new neighbor’s cat destroyed it while using the pot as his litter box. Anyway, a sad story.

Fast forward to 1999. At that point, I’d been married for about fifteen years and with my wife, Ildiko Repasi, we decided to move to upstate New York from Brooklyn to start a small niche fiber farm where we wanted to combine our love of animals and our arts training.1

We started raising Shetland sheep, Angora and Kashmir goats for fiber, Nubian goats for milk, and Boer goats for meat production. We had a total of about 200 head, as well as a variety of poultry.

We built a fully equipped felting studio, where we’ve produced artisan woolen articles and various home decor items using sheep skin and goat hide. In addition, we’ve shipped wool to a Canadian wool mill to produce blankets and also sent our Shetland fiber to Texas for rug production. We’ve used the goat milk for artisan soaps and other skin care products, and we sold lamb and goat meat, and poultry, at farmers markets as well as directly out of our farm and art studio. The shock treatment came early on when we discovered a major logistical miscalculation. The livestock regularly needed to be moved to new pastures to graze and, as it turned out, our rescued German Shorthaired Pointer and two Jack Russell Terriers were not up for the job.

We needed herding dogs…

Our newly elected two-member herding breed research committee (Ildiko and I), after an exhausting study, unanimously voted to get a rather obscure Hungarian herding breed; the Pumi. Our expert decision was largely based on nostalgia and unsupported legends, and heavily reliant on the distorted and fading memories of summer vacations spent at grandparents’ and other relatives’ homes and farms in the countryside of Hungary, Transylvania, and the Serbian Bačka region.

Finally, in the fall of 2008, Abiqua Dogos Csupasz, a four-month-old male Pumi puppy, arrived from Oregon. While we were excited at his presence, it dawned upon us that it would take a while before this exuberant, barking hairball was going to be able to herd. We signed up for herding training, and within four months, Csupasz was happily chasing sheep and goats… to everyone’s dismay.

He barked, nipped, and just was out of control. His work had to be suspended and training resumed with another trainer who understood “loose eye” dogs. Things started improving, and since we were desperate and in the middle of pasture season, we had to learn fast so that we could efficiently move the sheep and rotate the fields. What we learned in the morning, we tried to apply in the afternoon on the farm. By his 15-18 months of age, we started seeing light at the end of the tunnel.

Our “baptism by fire” approach has taught us a lot. As it turns out, Shetlands are a borderline feral-type of sheep and they tend to be pretty belligerent, always ready to fight dogs and, in general, they don’t flock well. They are not an ideal breed for beginner farmers and novice herding dogs.

Goats are famous for being stubborn and are tough on dogs when they feel that those they face might not be perfectly versed to do their job.

Most importantly, however, we’ve learned that without becoming fluent in the basics, herding can turn into major chaos on a farm. While giving the dog some room to be independent and apply its instinct, it needed the ability to make a solid “stop,” understand directions, make wide flanks, and respect its own threshold. We also learned something interesting about Csupasz. While he had a near perfect stop and also kept the threshold, the flock in front of him never stopped moving away. As it turned out, Csupasz had sort of a “semi-hard eye,” and even though he stopped and stood still, when he stared at the stock he appeared to be stalking them. To resolve this issue, we had to teach him to turn his head just enough so that the sheep stopped. Thus, he could keep an eye on them and still maintain control.

Finally, the combination of lessons, daily work, persistence, and consistency, as well as successes and failures, paid off and we gained the upper hand over sheep and goats. It is hard to explain the excitement and feeling of accomplishment that we felt seeing our dog move livestock from paddock to pasture, squeeze them through narrow gateways, and drive them along a half-mile trail through the woods to the summer pastures high up at the top of the property.

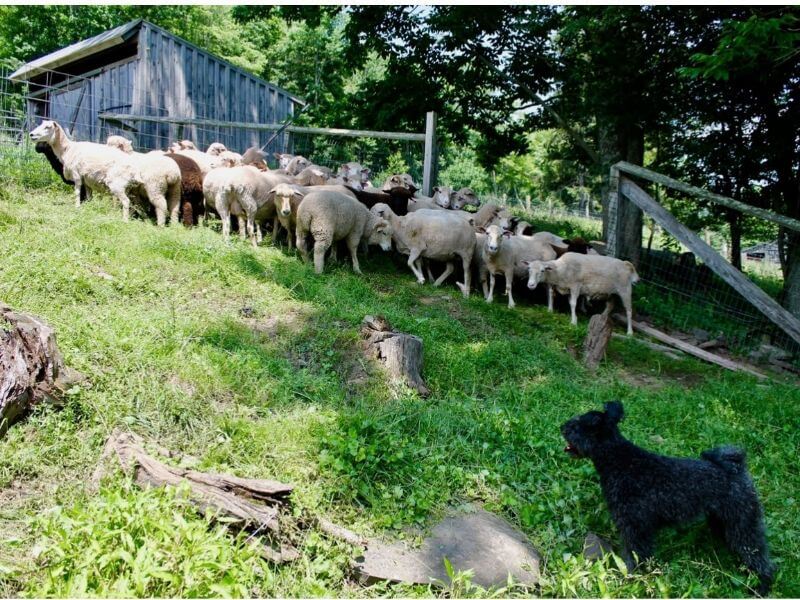

By 2012, we had three Pumik working on the farm: Csupasz, Fruska, and Agyag, all of them pretty competent at doing their jobs. Csupasz was the “bouncer,” taking care of rowdy and aggressive intact rams and bucks. Fruska took care of crowd control. She never hesitated to squeeze herself into the narrowest, most crowded corners to push the Shetlands along. She also learned “shedding” pretty well, and her presence was necessary during shearing, administering vaccines, and hoof trimming. Agyag has done general herding work, kind of a “Jack of All Trades.”

Our abridged knowledge of herding experience built some unwarranted confidence in ourselves and we decided to enter Herding Trials. Little did we know there is quite a difference between real-life farm herding and Herding Trials, especially AKC. Not surprisingly, we’ve learned the hard way via frequent “NQs” at trials that farm toughness does not translate well to Herding Trials. We had competed a couple of times for years, but could never get fully immersed in the exciting game of Herding Trials. In the Northeast, Herding Trial season is relatively short, from May to October, because of the harsh climate. Therefore, trials and trial venues are limited. In addition, the area is also short on qualified trainers and suitable places to practice. With a working farm and the curse of a busy Conformation show schedule, it has been complicated to fit in herding practices and trials, and traveling long distances.

Herding is a fascinating interaction between three different species; sheep, dog, and handler. There are different pressures at work during herding. When moving, feeding, or handling the livestock, the dog puts pressure on the sheep and must be able to handle pressure from the handler, while the sheep and the handler must be able to negotiate these alternating pressures between the sheep and the dog.

In a nutshell, the main difference between farm and trial herding is that on the farm we practice “my barn, my rules.” A herd can come in any configuration and dogs sometimes have to get physical with some sheep to get the job done, while at the same time being careful with younger lambs. The main goal is to ensure the safety of the herd, and reduce stress in pregnant ewes and young lambs with their moms. Last but not least, farm herding is also about productivity, and avoiding time and financial loss. A farm/herding dog is a tool, an investment that is an integral part of the farm operation where the dog contributes to making a living. Farm dogs work for a paycheck, so to say.2

In contrast, trial dogs, while most of them are highly trained and very obedient, are often micromanaged, and “tuned down” in order to comply with the rules of a highly choreographed game. This is, of course, necessary for the protection of the livestock at the event hosting farm. Trial sheep are usually selected from older ewes and castrated rams (wethers), and usually they are dog-trained.

During a trial, these sheep experience serious stress. Each new dog and handler entering the arena brings a different style and a different skill level. Trial participants herd for sport and recreation, with virtually no financial risk and zero investment in the livestock. They compete against the clock and to earn ribbons and titles. Most of the time, for the sportsman, the dog with whom he or she pursues this fun and exciting sport is really “just a pet” (for lack of a better term) at the end of the day.

The nuances of the game are also different for sport dogs and farm dogs. During a Herding Trial, there is a reasonable expectation about the quality of the stock and the safety of the course—with no real surprises. Through lots of practice, handler and dog become a well-coordinated team in order to succeed at challenging courses. It is exciting to watch highly skilled trial dogs.

On a farm, each day might be the same until it is not. When that moment arrives, a farm dog must be able to adapt on a dime to the new situation. When starting the day, there might be a storm-damaged section of the fence where the sheep got out or there might be an injured sheep, or a lost or isolated newborn lamb and a panicking, protective ewe. The dog must be listening to the handler and not attacking injured livestock or newborn lambs. A dog cannot be restrained (leashed) on a fully charged pasture where it would become vulnerable to the frightened stock. Dogs must be able to navigate through unexpected complications alongside the handler. In short, a dog cannot scream “fire” on a crowded farm… they need to stay obedient.

Farming is a dangerous job for dogs. Therefore, farm dogs need to learn impulse control, be desensitized to working near dangerous machinery, and obey in an emergency situation such as an unproductive birth on an open pasture, or to hold or remove young, stalking rams, etc. They have to be able to follow directions under pretty much any circumstances. They must respect property lines. They cannot touch free-range poultry or chase wildlife. Herding and farming can also take its toll on the dog’s body, and those injuries must be addressed.3

So, you may ask what specific tasks we do with our dogs in addition to moving the herd from place to place?

Our dogs help at feeding time. They hold a flock at bay either in the open or by “penning” them into a building until the feed is put out so that the sheep don’t run us over. They also do this during shearing. They do some “shedding,” for instance, when specific animals have to be removed from the herd for various reasons such as medicating, transportation etc. They help to push the sheep into a narrow, one-lane chute from a crowded building when we medicate and trim hooves or when lining up the sheep for shearing. They also drive the livestock up on the trails about half a mile through the woods to the summer fields. To see some of the work our dogs have done, I’ve added some YouTube links at the end of this article. They are obviously edited for brevity.

When we have puppies, I always hope that a few get a chance to become farm dogs and prove that a well-kept and well-trained Pumi is able to do farm work. We have a handful of Catskill dogs working on farms in Canada, North Dakota, Illinois, and Alabama.

The years have gone by fast and our first generation of Pumik have gracefully retired. Csupasz (15) and Fruska (13) are mostly rolling in fresh snow or on new grass, or selecting the best “sheep beans” in the barnyard these days. They also make it a priority that they get fed early and frequently. Agyag (11) is still working when work needs to be done. Barsony (8) is also on the payroll. She is especially good with young lambs when working with a mixed herd.

We’ve also been nurturing the next generation of herding Pumik. (Otherwise, the sheep would get away.) Of course, not all Pumik are created to be equal. The more talented ones are in training to work on the farm in the future. However, we try to expose everyone to herding.

Since COVID, we don’t use dogs with the same intensity as we did a few years ago. The pandemic has forced us to scale back our operation. Markets almost vanished, farm and studio visits were halted for a long time, wool processing has been delayed forever, and local small-scale slaughter houses could not operate for a while. In the same time, livestock idled on the pastures and did not stop eating. A huge amount of bagged wool, two season’s worth, has been piled up in the barn waiting to be processed.

Regardless, Pumik will remain an integral part of the farm. It’s been a great experience working with the breed for almost fifteen years and to be able to demonstrate daily that they can be reliable, competent, full-time working farm dogs.

When I reminisce about our journey once in a while, I always wonder how my life would have turned out if I could have protected Mrs. Silberblatt’s potted geranium from that obnoxious cat in Budapest—perhaps with a herding Pumi?