How a Faulty Judge Ended a Dog’s Career – And Other Judging Thoughts

Up until August of this year, I owned the #2 Basset Hound in the country. I am so proud of this dog! At 6, this dog was outperforming most other Basset Hounds being shown, and I bred him. I showed him myself for most of the past 4 years, but let my handler, Kellie Miller, take him out for his last year as a special. She travels a lot more than I do, and I wanted to keep him out until December to keep up his ranking.

He could not be shown at our National in October because I was judging the specialty the day before, so we made the decision to show all the way to the end of the year. In April of next year he will be old enough to show as a veteran. However, in August his career was ended abruptly by a judge who not only fault judged, but one who was determined to validate a previous judges’ decision, regardless of the dog’s other merits.

This particular dog has the most annoying ability to pull his testicles up out of his scrotum and into his body. He uses this trait sparingly, so it was a shock the first time a judge commented that he could only find one testicle. On that day the judge asked to see the dog move, then put him back on the ramp, and the judge found that both had descended into the scrotum. He went on to win BOB. It was a wake-up call for Kellie, who then had to make sure he did not pull that unwelcome trick again. Things went along fine until the first day of the Greeley 5-day circuit in August, when the dog again pulled one testicle up while being examined on the ramp.

Except the judge that day thought he was actually feeling 2 testicles that were grossly uneven in size. I am guessing he thought the dog’s thick, toughened skin of the scrotum was the second testicle. This judge disqualified the dog for testicles of unequal size. Kellie left the ring gracefully, checked the dog’s testicles which were both now descended, and asked another long-time Basset breeder who had a dog entered that day for his opinion about the size. The breeder found no significant difference. Nor did the AKC rep when Kellie brought the dog to her for a check. She called me, and we discussed how to proceed with the rest of the weekend.

I decided to leave the dog in competition, but cautioned Kellie to make sure he did not pull up testicles on the ramp again, or excuse herself if he did and she could not bring them down in time for the exam. And that is exactly what she did. The next day she stacked the dog on the ramp and checked to make sure both were descended before the judges’ exam. They were, and the judge found both of them. He asked Kellie to move the dog, then had her put him back on the ramp where he proceeded to aggressively grope for the dog’s testicles again. This time the dog pulled both testicles up, and he was disqualified a second time, this time for

having no testicles.

For those who don’t know, 3 disqualifications for testicle issues will render a dog unable to ever compete again. Period. There is no appeal procedure, and it is always entirely the judges’ discretion whether to disqualify a dog on that day. The AKC cannot override the decision under any circumstances. I have no issue with the first judge on the weekend who found only one testicle, and likely made a mistake about the second one which the dog had pulled up.

However, I take great issue with a judge who aggressively seeks to disqualify a dog in order to publicly validate his friend’s initial decision, which was valid, but probably based on a misunderstanding of what he was feeling. Several people witnessed the two judges talking before Bassets entered the ring. I have no doubt the disqualification from the day before was discussed. The second judge was determined to rescue the reputation of the first day’s judge, and ending my dog’s career when he knew the truth was irrelevant.

I have since had a complete and thorough evaluation of this dog by a reproductive specialist who has concluded that the dog’s testicles are completely normal for his age, and he is certainly capable of reproducing with plenty of normal, viable semen. None of that matters, however. He has been disqualified twice, so his long career as a Special ended the day of the second disqualification. I want to be able to show him occasionally as a Veteran, so I was unwilling to take a chance on a third disqualification. I am still proud of what he has accomplished—a lot of it with a breeder-owner-handler on the end of the lead.

A dog cannot reach the #2 spot in the country with only one testicle. All of those judges cannot be wrong—for 6 years. I don’t understand why the day 2 judge was so determined to disqualify a dog after he verified to himself that the dog actually had 2 equal-sized testicles. I think a judges’ duty is to find the best overall quality in the dogs he judges without any other agenda. Fault judging is never a good idea, and aggressively pursuing a disqualification

on a highly ranked dog is mean-spirited

and unnecessary.

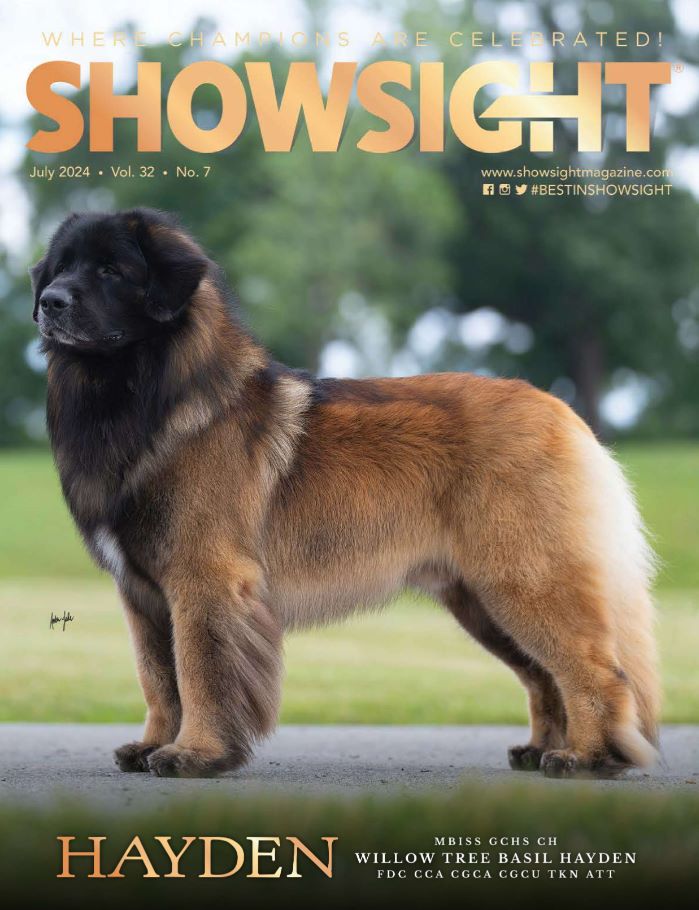

This year I had the good fortune to be asked to judge a Basset specialty the day before the National in Denver. I usually don’t get to these shows because I am travelling out to Montgomery County with Bedlington Terriers the same week these shows. But this offer was too good to pass up, even though I had a competitive Basset Special this year. It was a thrill to be able to judge all of the classes in a show the day before the main event.

Although the entry this year was relatively small for our breed, I thought the quality was exceptional. In many classes all of the dogs in the ribbons could have won. In one class my test of fault judging vs. whole dog judging was put to the test.

In the 9-12 puppy dog class I had 4 outstanding dogs pulled for my finalists. I examined and moved them all, and watched as they struggled to set-up their 40-pound bags of Jell-O masquerading as Bassets. I had a tough decision. One of the young puppies had some obvious issues. His feet were a little turned out, he had a slight rise over his loin, and he did not want to stand on all four legs for more than about 2 seconds. But when I looked at the whole dog, he was magnificent.

His profile was proportionate, his long neck flowed into beautiful, clean shoulders, his head was beautiful, his angulation in front and rear was amazing, and he had better reach and drive than I have seen in a long time. His handler struggled to keep him standing, but that did not bother me. I saw everything I needed to see when the dog floated around the ring. He was my choice to win the class, and ultimately, he was my choice for Winners Dog. I fully expected to hear a lot of complaints about the faults I obviously missed, but I didn’t.

I was prepared to defend my decision, but I really did not need to do that, either. Several long-time breeders expressed a lot of support for my finding a young dog that was so beautifully constructed, even if he was pretty immature. They appreciated my breeders’ perspective. I did not want to go with a safe selection, middle of the road, not too bad and not too great. The minor faults the dog had were insignificant to the whole picture.

The qualities that our standard stresses as important were all found in this dog, and the minor faults were likely to correct with age. If I had been a fault judge, I would have made a different choice, a safer choice. I am very happy with the choice I made because it was the result of looking for the positives, not trying to find the negatives. I am looking forward to following this young dog’s career as he matures.

The old-time judges who mentored me, many of whom are no longer with us, always stressed the importance of looking for the positive traits in dogs. They loathed the fault judges who would pick a trait and focus on that one thing as though it was all that was important in the breed. I still hear some of the phrases that indicate too much focus on a single trait, e.g., “no tail, no basset!”

I think many judges have forgotten that their role is not to find the safe dog, but to identify and prioritize traits to find the best dog. Fear of making a mistake has led to a lot of safe, generic judging. In the case of my now retired special, the fault judging was even worse because it had more to do with a judges’ ego than it did with the breed he was judging. There is no place for this type of judging in our shows.