Judging the Afghan Hound

The Afghan Hound is an eye-catching, glamorous member of the Hound Group. Do not let this star-quality fool you! The Afghan Hound is a medium-sized hunting hound, and every component of the Breed Standard describes a hound built for speed, agility, and senses exquisitely honed to catch and kill various game with enthusiasm and efficiency. The Afghan Hound differs greatly from most of the Greyhound-like breeds in outline and proportions. Whereas the Greyhound-type is slightly longer than tall, with the outline a series of sinuous curves, the Afghan Hound is square and angular. The Afghan Hound originated in areas of vast deserts and mountainous terrain. His construction sacrifices some in speed for the ability to stop, turn, and climb, not unlike a Quarter Horse in these characteristics.

You need only talk to any military veteran of service in Afghanistan to hear of the unforgiving variations in weather and terrain in that country. There are desert areas and fierce mountain ranges, torrid heat and biting cold. The early Afghan Hounds were of two types, one primarily situated in the desert areas and those primarily habituated to the mountains. Over time, and relocation to other countries, these types have been interbred for a combination of the best of each type (ideally) so that the results are not recognizable as clearly either side of the road.

The origins of the Afghan Hound, as of many of the ancient sighthound breeds of the Middle East, are a combination of fact, fantasy, and speculation. The diversity is not random but follows geographical considerations. The Afghan Hounds of the lowland region of Southern and Western Afghanistan lean further toward the sparse coat and racier build of the other sighthound types of the region. In contrast, the Afghan Hounds of the more rugged mountainous terrain of the formidable Hindu Kush tend to be a bit shorter, with a stronger, more powerful build and much more heavily coated to withstand the rigors of the weather. No matter the terrain, these dogs traveled with the nomadic tribes of the region, serving in various capacities as hunter, herder, and sometimes, babysitter. For a more comprehensive history of the breed, see The Complete Afghan Hound (Miller & Gilbert) and Connie Miller’s excellent treatise, “The Truth in Gazehounds,” published in the July and August issues of the Gazehound, 1980.

The cornerstone of the Afghan Hound as we know it today started with the Standard written primarily by Mrs. Amps in England, President of the Afghan Hound Association. She was the guiding force as an importer and breeder, with actual working knowledge of these hounds in their native habitat. This Standard, written in 1927, was to supersede the first, written two years earlier, and clearly pointed out the differences between the Afghan Hound and other, related sighthound breeds. In 1947, The Kennel Club in Britain adopted the one Standard that took precedence over the competing Standards of the various local breed clubs. The American Standard was adopted by the Afghan Club of America in 1948 and remains (thank Heaven) unchanged at this time.

The essential qualities that make the Afghan Hound unique are spelled out wonderfully in the “General Appearance” section of the Standard for the breed. These are qualities that set the breed apart from even his closest relatives and are necessary for the selection of a correct Afghan Hound specimen. As a judge, you are charged with finding the hound that most closely epitomizes the qualities listed here without falling prey to the newest trends and handling quirks that we frequently see in the ring today. The General Appearance section that opens the AKC Afghan Hound Breed Standard states:

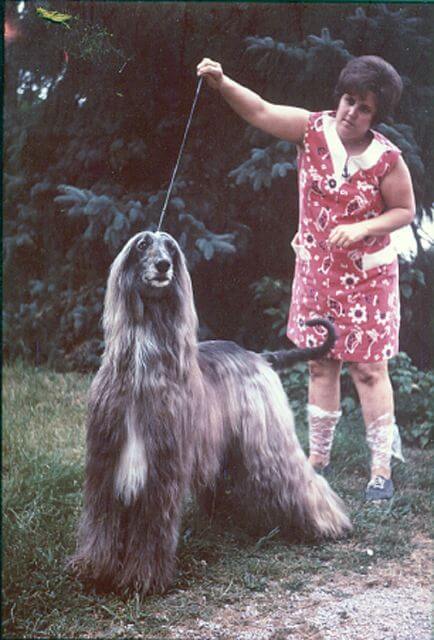

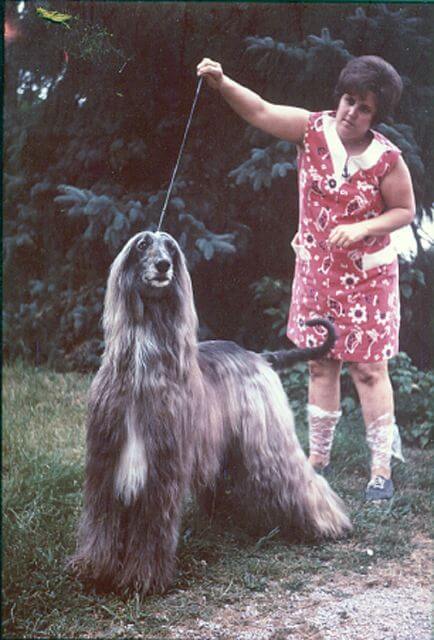

“The Afghan Hound is an aristocrat, his whole appearance one of dignity and aloofness with no trace of plainness or coarseness. He has a straight front, proudly carried head, eyes gazing into the distance as if in memory of ages past. The striking characteristics of the breed-exotic, or “Eastern” expression, long silky topknot, peculiar coat pattern, very prominent hipbones, large feet, and the impression of a somewhat exaggerated bend in the stifle due to profuse trouserings-stand out clearly, giving the Afghan Hound the appearance of what he is, a king of dogs, that has held true to tradition throughout the ages.”

There you have it… a thumbnail description of a hound different from all the rest by virtue of these highlights. The rest of the Standard fills in the blanks in greater detail. The one necessary point that does not appear in the General Appearance section is the insistence on a square dog. Your first impression on looking at a line of dogs in a class that has come in the ring is to search for a square dog. The Standard insists on it, and you should, too. When you approach a hound to examine it, he should stand his ground and look through you as if you didn’t exist. The Afghan Hound is an aristocrat and the judge is a lesser being… to be tolerated, but not fawned over. Part of this is also that the Afghan Hound is far-sighted, and sees objects better farther away. The Afghan Hound owns the ground he walks on. Self-confidence is paramount. The Temperament section is very sparse: “Aloof and dignified, yet gay. Faults are sharpness or shyness.” Examining the head, the skull is evenly balanced with the foreface, with a slight rise over the nasal bone. There is little or no stop. Eyes are dark and appear triangular, adding to the exotic expression. This look is further enhanced by the chiseling on the muzzle, low set, long ears, and profuse topknot. Bite is either level or scissors. The nose is large and black. It is impossible, without outside help, to have a black nose on a cream dog, but the Standard is unforgiving—wanting a black nose in all colors—something the founding fathers (mothers) failed to consider.

A phrase that causes some confusion is that of calling for “a straight front.” This is a seeming contradiction, as the Standard is very clear that the front construction is anything but “straight.” As the Standard is very clear that the front should be set back on the body, with well-angulated shoulders and an upper arm of equal length and layback, the straight front is the elbow to ground in a straight line from front or side. Indeed, the Standard admonishes, “Shoulders have plenty of angulation so that the legs are well set underneath the dog (emphasis mine).”

The Afghan Hound’s front has to pull him as well as provide stability, and, of course, must be equally balanced with the rear angulation. One of your greatest challenges in judging this breed is to find the point of shoulder behind the sternum and the legs set under the dog. Most exhibits nowadays have the Afghan Hound posting like Saddlebreds on parade. With the front legs ahead of the nose.

We spoke before of the greyhound-like breeds being a series of curves and a longer-cast body. The Afghan Hound is distinctly different. He sacrifices a bit in speed for the ability to stop and turn to follow his quarry up and down mountainous terrain and to make the quick turns that his prey will make to try to elude the hunting hound. The Afghan Hound is SQUARE, the height at the withers equals the length from chest to buttocks. The structural components are a shorter body with a level topline, equal and balanced angulation, low hocks for propelling power, and the unique pelvic construction for maximum propulsion. The croup (pelvis) is long and sloping (at about 30 degrees), with prominent hipbones, and the tail is set low… long and feathered, with a curve or curl at the end. After all, the hunter has to be able to see his dog. Feet are big, with deep, thick pads for shock absorption and the ability to withstand desert heat and mountain cold. The rear is not over-angulated; the Standard’s requirements are for “…the impression of a somewhat exaggerated bend in the stifle due to profuse trouserings.” The great, sweeping rear angulation that overpowers the front is not what is desired. Balance is the key. From the rear, there should be a slight bow from hock to crotch… like a cowboy in chaps.

The Afghan Hound’s coat is his crowning glory… and his deepest shame due to overzealous owners and handlers who feel that they have to improve on nature. My admonishment, like the ad from years ago, is: “Don’t mess with Mother Nature!” The Standard calls for “Hindquarters, flanks, ribs, forequarters, and legs well covered with thick, silky hair, very fine in texture; ears and all four feet well feathered; from in front of the shoulders… along the saddle from the flanks and the ribs upwards, the hair is short and close, forming a smooth back in mature dogs (emphasis mine).” This is a traditional characteristic of the Afghan Hound.

“The Afghan Hound should be shown in its natural state; the coat is not clipped or trimmed (emphasis mine).” “Showing of short hair on cuffs on either front or back legs is permissible.” You will see this especially on bitches after a seasonal coat drop, though it may appear in males as well and is a lovely sight.

Faults: Lack of a short-haired saddle IN MATURE DOGS (caps mine). I have put sections in bold or CAPITAL letters, as you will have in your ring six-month-old puppies with saddles plucked or shaven in, and faces and necks shaved to the skin. When I returned to judging after a 10-year hiatus working for the American Kennel Club, I found many shaved faces and plucked saddles. I spoke of this to my friend and passionate Afghan Hound breeder, Babbie Tongren, who vehemently said, “Throw the bastards out, Midge. They need to learn not to do it.” While I agree in principle, I know of people who have (and have, myself, on occasion) trimmed a dog so that you can’t really tell it has been accomplished. So, in my cowardly way, I suppose I reward good trimming and penalize bad trimming—or blatant trimming. I also hate to penalize a good dog for his owner’s disregard of the Standard’s requirements.

The Afghan Hound gait is very difficult to describe, but once seen, or felt through the lead, is never forgotten and always to be sought. The Standard begins by describing the dog at a gallop, “showing great elasticity and spring in his smooth, powerful stride. When on a loose lead, the Afghan can trot at a fast pace…” (the Standard says CAN —it doesn’t have to go at breakneck speed!); “…stepping along, he has the appearance of placing the hind feet directly in the foot prints of the front feet, both thrown straight ahead. Moving with head and tail high, the whole appearance of the Afghan Hound is one of great style and beauty.” If the dog is gaited too fast, the rear feet will overtake and pass the front feet, which is unacceptable.

NOW… much has been written and told in describing proper Afghan Hound gait. “Fast pace” is a relative concept. The doyennes of the breed, Kay Finch and Sunny Shay, did not gait their dogs at 90 miles an hour. Films and tapes (and observations of Kay with her stately Crown Crest dogs) had a smooth-running walk that had the dogs at a collected “Reconnaissance trot” with head and tail high. Sunny had a run, but she took shorter steps with a higher knee action, not terribly fast, but still not the dead-run seen far too often in the ring today. The judge is in control of the ring; you can control the speed. The Afghan Hound’s natural trot is utilized for searching for prey—or predators—and is accomplished with head and tail held high. In any breed, as speed increases, the center of gravity shifts and the head is extended farther forward… not what is wanted in the show ring for this stately hound. The elasticity and spring the Standard describes at the gallop is also seen at the trot. Spring and elasticity DO NOT equal bounce… the stride is smooth and powerful, covering ground efficiently and easily. I quote from an article from Australia, from 2002:

“Nature has evolved a style of gait called the ‘Reconnaissance trot.’ The head is carried high as the hound rises to the trot. There is the impression of a smooth, springy gait or a floating gait, with effortless reach and drive. What leaves a lasting impression is the cadence of this gait when performed by a well-balanced Afghan. The cadence (or symmetry) is where the trot is of moderate speed and the reach and drive finalize each stride simultaneously and there appears to be a momentary pause before the outreached limbs gather for the next stride. At the fullest extension, the limbs are straight. There is no bend at the elbow. Integral to the ability to gait in this renowned manner are several factors which, if deficient, will greatly impact the dog’s performance: temperament, intelligence, health, fitness, and balance. Together, these factors make for a memorable gaiting Afghan Hound and a joy to behold.” This article was written by Terrence Wilcox, Alaqadar Afghans, with reference to other breeders, some from Afghanistan.

In teaching, you must boil down the key concepts into a few choice words to remember. For the Afghan Hound, I have five key concepts: The correct Afghan Hound MUST be:

- Aristocratic

- Square

- Balanced

- Angular

- Athletic

He must have type and structural, physical, and mental soundness, strength, and conditioning.