Home » Alaskan Malamute Dog – Fit for His Environment & Function

The Alaskan Malamute dog was an essential part of the Mahlemiut tribe in Alaska and was part of the family for hundreds of years. They were used for travel and to pull heavy sledges with supplies and killed game. It is a natural breed, evolved to fit into his environment and function.

The breed was used extensively by Admiral Peary in Arctic explorations and by Admiral Byrd in Antarctica expeditions. Along with other sled dog breeds, Alaskan Malamutes were stationed in Antarctica during World War II. Tragically, after the war was over, they were destroyed since the military no longer had a use for them. Fortunately, today, war dogs are brought back home, but this is a recent policy of the past 30 years.

In 1935, Short Seeley, a pioneer of the breed in the lower 48 states, obtained AKC Malamute recognition based on the Alaskan coastal Kotzebue bloodline. There was another major line, M’Loot, used inland, but those breeders were not interested in AKC recognition and were not registered at that time. Eventually, those dogs were brought down to the lower 48. With so few registered Alaskan Malamute dogs left after the war, AKC opened the stud books to non-registered Malamutes that could win 10 points in the conformation ring, which replenished the breed. This lasted for a few years and then the stud book was closed. This also allowed the M’Loot line into AKC recognition.

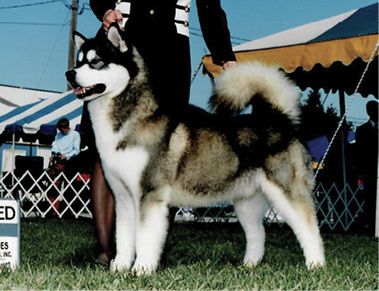

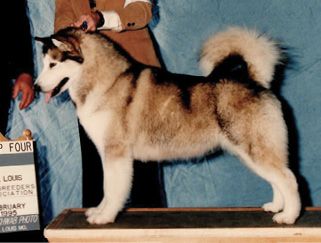

From the AKC Breed Standard: “The Alaskan Malamute must be a heavy boned dog with sound legs, good feet, deep chest and powerful shoulders, and have all of the other physical attributes necessary for the efficient performance of his job. The gait must be steady, balanced, tireless and totally efficient. He is not intended as a racing sled dog designed to compete in speed trials. The Malamute is structured for strength and endurance, and any characteristic of the individual specimen, including temperament, which interferes with the accomplishment of this purpose, is to be considered the most serious of faults.”

From the AKC Breed Standard: “The Alaskan Malamute must be a heavy boned dog with sound legs, good feet, deep chest and powerful shoulders, and have all of the other physical attributes necessary for the efficient performance of his job. The gait must be steady, balanced, tireless and totally efficient. He is not intended as a racing sled dog designed to compete in speed trials. The Malamute is structured for strength and endurance, and any characteristic of the individual specimen, including temperament, which interferes with the accomplishment of this purpose, is to be considered the most serious of faults.”

The Standard, from beginning to end, emphasizes the traits needed to perform as a heavy sledge dog in the Arctic. A good way to interpret the Standard is to break it down into survival, performance, and cosmetic traits. Of course, balance is important with all the parts fitting together.

Survival Traits – Essential

The Alaskan Malamute dog had to survive in the severe environment of Alaska, which requires a coat to stay warm and repel snow and rain. Also, almond-shaped, obliquely-placed eyes and small ears are important. They can handle 80 degrees below zero without discomfort. The guard coat is thick and coarse, never long and soft. Soft coats will absorb snow and rain, and freeze into ice in cold weather, which would weigh down the dog—which would then have trouble surviving. While different dogs may have different lengths of coat, the texture is the important trait to withstand the weather. A shorter-coated dog shouldn’t be penalized if it has good texture. Dogs with correct coats will still have good texture, even when out of coat. The Alaskan Malamute dog is shown naturally. Trimming is not acceptable except to provide a clean-cut appearance of the feet.

Performance Traits – Essential

Structure and movement are essential to work all day long along with the substance to have the strength to pull heavy loads. Of all the Working breeds, the sled dog breeds often had to work the longest as compared to guard dogs that may do a perimeter round and watch over the herd or inspect a building or grounds. Plus, the sled dog breeds were pulling loads. The Alaskan Malamute dog needs to have enough substance and strength to pull heavy loads efficiently over great distances.

Cosmetic Traits – Desirable but Not Essential

These are things that do not directly affect the Malamute’s ability to survive and effectively do its job. Yes, they are desirable, but they are not essential to be a freighting sled dog. For example, dark eyes are preferred, but much more important is the almond shape to withstand severe weather conditions.

A Hands-On Breed

With their extensive coat, it is a must to thoroughly exam the dog, feeling through the coat. Visual inspection can be deceptive, especially with optical illusions of markings and coat.

Size – The Alaskan Malamute Breed Standard is one of only two Working Breed Standards which do not give an explicit or implicit size range. Judges often overestimate the breed’s size, due to the dogs’ substance and coat giving the appearance of being bigger than they really are.

The history of the breed goes back to two predominant bloodlines; the Kotzebue dogs from the coastal area and the M’Loot dogs inland, which were a larger style. Both lines worked well in their environment and, over the years, have been cross-bred, with no “pure” dogs today of either line. Contrary to what many people think, the breed is not getting bigger but has become more uniform.

The Standard states: “There is a natural range in size in the breed. The desirable freighting sizes are males, 25 inches at the shoulders, 85 pounds; females, 23 inches at the shoulders, 75 pounds. However, size consideration should not outweigh that of type, proportion, movement and other functional attributes. When dogs are judged equal in type, proportion, movement, the dog nearest the desirable freighting size is to be preferred.”

So, size is a tiebreaker when dogs are equal. Dogs should be judged first for overall quality and only when equal should size be considered. Judges need to have a system of estimating size. Some judges use a pin attached to their dress or pants. Some use their fingers as a reference. Visual estimates can be misleading due to the substance and coat of Alaskan Malamute dogs. At our recent seminars, judges are asked in their critiques to estimate size. Judges often overestimate by an inch or two—or even more.

Proportion – The Standard does not give a precise body length-to-height ratio, but states: “The length of the body from point of shoulder to the rear point of pelvis is longer than the height of the body from ground to top of the withers.” “The body is compactly built but not short coupled.” Breeders feel that slightly longer than tall is appropriate. At National Specialties, we have measured 100 dogs that were in the Top Twenty, National Specialty winners, other champions, and excellent sled dogs with working titles. We measured from point of shoulder to rear point of pelvis. Most dogs were very close to 10/9 (length-to-height). The bitches’ proportions, surprisingly, weren’t significantly different than the males.

Leg length should be about half the height at the shoulders. The dogs we have measured were slightly more than half; we measured to the top of the elbow, which is a more precise point. Most dogs’ legs were 52-54 percent of the height. What is often misleading are dogs with heavy coats and deep chests, which give the optical illusion of short legs. This is amplified with the white on the legs stopping well below the elbow. It is necessary to feel for the elbow during the exam and also to observe the length of leg on side gait. Of course, excessively long legs are incorrect.

Head – The skull is broad with a large and bulky muzzle that blends into the skull. A broad skull will have ears far apart as an indicator. When the ears are close together it usually is an indication of a narrow skull, though high set ears can also give this appearance. Skull/muzzle length isn’t described in the Standard. Our measurements were generally a 3-to-2 ratio of backskull to muzzle proportion, orvery close to it. It was measured to the inner corner of the eye for muzzle length as this is a precise point instead of only referring to the stop, which is an inch or more and is an ambiguous reference for measuring.

Ears – Small ears are desirable because they would lose less heat than large ears. Arctic animals such as arctic wolves, rabbits, polar bears, etc., have small ears as these are needed for that severe environment.

Eyes – These should be almond-shaped to better withstand wind, snow, sleet, etc. Dark eyes are preferred. Some breeders emphasize dark eyes as they affect expression. I consider eye color to be cosmetic, and while I appreciate dark eyes, I don’t worry about them too much unless they are extremely light.

Nose – Snow noses are perfectly acceptable.

Bite – A scissors bite is correct. Overshot or undershot is a fault.

Feet – For endurance, correct feet are very important. They are large and snowshoe type, tight and deep, with well-cushioned pads, and compact. Snowshoe type means large, better to walk across snow without sinking in as much. Cat feet are undesirable as they don’t hold up as well on the trails. The Siberian Husky Standard calls for oval feet, and the Samoyed Standard calls for “Large, long, flatish-a hare-foot…” and adds “cat-footed” is to be faulted.

The previous Standard had a scale of points (AKC didn’t allow this at the time of the revised Standard) giving feet 10 points out of 100. They should not be overlooked.

Colors – From the Standard: “The usual colors range from light gray through intermediate shadings to black, sable, and shadings of sable to red. Color combinations are acceptable in undercoats, points, and trimmings. The only solid color allowable is all white.” While there is a wide range of acceptable colors and shadings, there are no preferred colors. All stated colors are equal.

Gait – Gait is balanced and powerful with good reach and strong rear drive, with a solid, level topline. The head drops forward as he moves; not quite to the horizontal. The feet will converge toward the centerline of the body. Movement should be smooth and effortless. The Standard, under “Neck, Topline, Body,” states, “The back is straight and gently sloping to the hips.” There has been some confusion that this refers to the dog moving as well as standing. This is an indication of rear angulation when standing. When moving, the head drops, which levels out the topline.

Tail Carriage – Sometimes tail carriage is over-emphasized in judging. From the Standard: “The tail is carried over the back when not working. It is not a snap tail or curled tight against the back… has the appearance of a waving plume.” While the waving plume is desirable, it is not essential for the dog to do its job. Tail-set is an important part of structure, but tail carriage is not. I think tail carriage isaffected by muscles and tendons. It often changes during aging. It’s not unusual for a tight tail on a young dog to loosen up with age. Twenty-five years ago, there was an “outbreak” of tight tails from many different bloodlines. Several interested breeders, including myself, measured dogs with tight tails and correct tails. We measured pelvis length and angle, and croup angles, and could find no correlation. Alaskan Malamute dogs can put their tails anywhere they want depending on how they feel. Tails don’t have to be up all the time, but should be during some of the time in the ring. When moving, some dogs carry their tails up while others have tails that trail, which is fine. Bitches, in particular, often have their tails down much of the time. Males more often have their tails up, especially when bitches are nearby. The previous Standard’s scale of points allotted five points for Tail. I consider tail carriage to be more of a tie-breaker.

Bitches Deserve Equal Consideration – While males give a more impressive appearance with their substance and more coat, bitches should still be considered when they have appropriate type and movement. It’s hard to campaign a bitch, as they usually blow coat twice a year and are in full coat for only four to six months as they go out, come back in, hold coat, and then go through the cycle again.

Personality – Generally, Malamutes are happy-go-lucky and are glad to see everyone. Oftentimes, they can be fidgety and are not always willing to stand perfectly still. Puppies can be especially restless and should be given some leniency. It’s all part of their personality. Approach and examine with confidence. On rare occasion, you may come across one with a questionable temperament. If in doubt, excuse the dog if you’re uncomfortable.

Summary – From the Standard: “IMPORTANT: In judging Malamutes, their function as a sledge dog for heavy freighting in the Arctic must be given consideration above all else. The degree to which a dog is penalized should depend upon the extent to which the dog deviates from the description of the ideal Malamute and the extent to which the particular fault would actually affect the working ability of the dog. The legs of the Malamute must indicate unusual strength and tremendous propelling power. Any indication of unsoundness in legs and feet, front or rear, standing or moving, is to be considered a serious fault.”

IMPORTANT: In judging Malamutes, their function as a sledge dog for heavy freighting in the Arctic must be given consideration above all else.

The current Standard has the same essence as the original 1935 Standard, emphasizing the importance of the traits to be a functioning sledge dog. Some of the wording is identical. The breed has not changed drastically from the early days, and past years’ top dogs would be competitive today.

Please review the AKC Judges Study Guide website and AMCA Judges Education page for the latest Judges Education Materials, including the Illustrated Standard, Slide Show Presentation, Color Guide, and Mentor List. Especially check out the video of Malamutes waking up after a snowstorm to get an idea of the extreme weather Malamutes lived in.