Home » Balance in the Canine

What is meant by “balance” in the dog? The AKC Glossary defines balance as “BALANCE: When all the parts of the dog, moving or standing, produce a harmonious image.” As a self-taught artist, I became aware of the Golden Ratio (or golden or divine proportion), a ratio between two numbers equal to approximately 1.618 (most often written as the Greek letter “phi”). This ratio was published in Euclid’s Elements, the Classical Greek work on mathematics and geometry. Two hundred years later, the proportion was paired with illustrations by Leonardo da Vinci, which established the ideal balance in the human form and praised the ratio as representing divinely inspired simplicity and orderliness. Artists reference da Vinci’s illustrations to this day, and the Golden Ratio is still used in art and graphic design.

Da Vinci determined the two forms of balance in the human—horizontal and vertical. Da Vinci determined that all terrestrial animals resemble each other in this manner, and the same rules apply to the four-legged animals as they do the two-legged man.

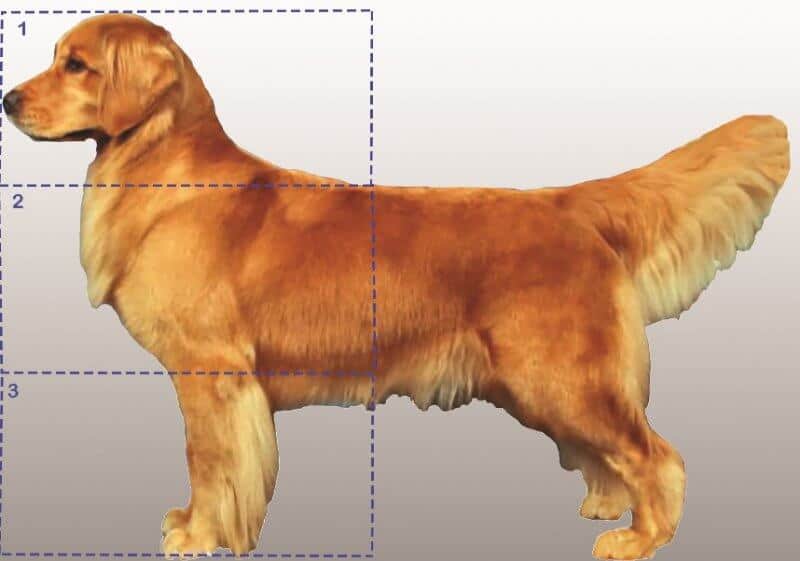

Vertical Balance is the relationship of the areas that make up the dog’s height: the head and neck, the body, and the leg. A balanced dog of any size will show the same relative proportions of these three areas: roughly one-third head and neck, one-third body (thorax or chest), and one-third length of leg. These proportions apply to any breed (obviously, short-legged and dwarf breeds are the exceptions). Should a dog fail to conform to the “one-third rule,” it either lacks in length of neck or is short in length of leg.

In an earlier article, I pointed out that all dogs (all mammals—even the giraffe!) have the same number of cervical (neck) vertebrae; seven. They only differ in size and length among the various species of animal. A “short neck” in a dog is always caused by an upright shoulder, not a difference in the actual length of the neck. An upright shoulder covers up much of the neck, giving the illusion of a dog with a short neck. Therefore, if the head and neck make up less than one-third of the height, the dog is out of balance.

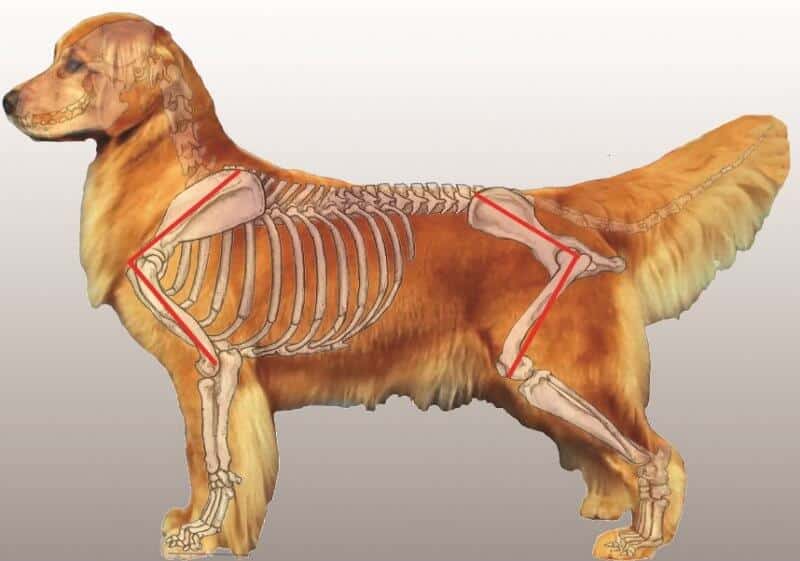

Horizontal Balance is much easier to comprehend. It speaks to the balance in the angulation of the dog, fore and aft. In a horizontally balanced dog, the angle of the articulation of the shoulder blade (scapula) to the upper arm (humerus) at the point of the shoulder equals the angle of the articulation of the pelvis (hip) to the upper thigh (femur) at the hip joint. (See Figure 2.) These angles oppose each other (example: < —- > not < —- <).

Unfortunately, many breeders, and even worse, many standards, think that the forequarter angulation matches the angle formed at the dog’s stifle. This is NOT correct! The stifle should oppose the elbow (example: > —- <). A dog with a well-laid-back shoulder and correct length of upper arm has an angulation of approximately 90 degrees. (*Please refer to the notation at the end of this article.) The same angle should be found at the junction of the hip and thigh, to balance with the angulation of the forequarters.

Both Rachel Elliott and Curtis Brown state in their books that the moderately angulated dog (Retrievers and Herding Breeds) have a shoulder placement of approximately 120 degrees, and dogs built for speed have a more upright shoulder placement of approximately 130 degrees. As with the well-angled dog, those with a moderate and more upright shoulder blade should have approximately the same angulation in the hindquarters at the hip and upper thigh junction.

A dog can have a lack of angulation fore and aft and still be balanced—as long as the rear mirrors the front. Think of a herding dog that has an upright shoulder and a steep pelvis; they move with a balanced trot but take far too many steps to cover the same amount of ground as a dog that is well-angled at both ends. It is far better to have a dog with a balanced lack of angulation than one that is straight in front with a well-angled rear. The first dog will be exhausted at the end of the day, but will be able to work the next day. Unfortunately, the dog that is out of balance will eventually break down in the front and will no longer be able to fulfill the work he was bred to do.

While observing a class of veteran dogs at a national specialty, I was rather astonished at how many of the dogs seemed to be high in the rear. Think about this for a moment: Several were top-winning dogs in their prime. As I continued to observe the class, it dawned on me that they were not running up behind but were sagging in the front! Each dog was straighter in front than in the rear, and the proof of the breakdown in the fore assembly was right in front of me. The front assembly of the dog is attached to the body only by muscles and ligaments. The dog’s rear is much more stable simply because the sacral vertebrae (croup) are fused to the hip. No wonder the front often fails in a dog that is out of balance horizontally.

So many standards prize overall balance in the dog because it helps the dog move more efficiently, with less energy expenditure. Generally, a dog unbalanced in angulation takes more evasive actions with its legs and body to keep the feet from interfering with each other. By doing so, the dog expends a great deal of energy to overcome the problem.

Many things influence the dog’s movement, but the angulation of the forequarters and hindquarters (plus the dog’s overall physical condition) are the significant factors. The dog’s “heart” or spirit/desire is another factor, but it is one which cannot be measured with a tool or the eye of the beholder. A dog with “great heart” will often overcome his physical limitations because of his intense desire to hunt, herd, track game, etc. Dogs with such spirit and good conformation are the super dogs that excel in all they attempt to do. On the other hand, dogs lacking in areas of conformation with great hearts can get the job done, but it is sometimes at even greater expense to their body.

A balanced dog, whether balanced in good angulation or lack of angulation, may be tired at the end of the day, but with rest it will be up to work another day. A dog with great heart, but lacking in balance, may perform brilliantly at its work, but will have a shortened career when the lesser part (usually the front assembly) begins to break down. Most breeds tend to single track, especially those from the Sporting, Hound, Working, and Herding Groups.

To observe side gait, you not only watch the action of the feet and legs, but the motion of the body—both laterally (side to side) and vertically. Movement over the topline (especially at the withers) can indicate several faults. When there is vertical movement (up and down) over the withers, this is usually caused by steep shoulder blades (blades that point upwards rather than toward the rear of the dog). Upright shoulders cause either short, choppy steps or cause the dog’s rearing muscles in the hindquarters to lift the front off of the ground to lengthen the stride. An up-and-down motion over the withers is also a sign of a faulty front. In coated dogs, such faulty movement is pointed out to the observer; canine movement should always be forward, not up and down along the backline.

When watching the topline, ask yourself, “Does the dog’s back at the withers glide forward or bounce up and down?” Often, a dog with steep shoulders also has a topline that slopes toward the rear. Even if the standard calls for a sloping topline, this should not be attained due to a loss of shoulder layback. Some dogs that are balanced front to rear, but lack angulation, can be likened to watching a child’s rocking horse in motion. The rocking movement of the dog belies a spine that is not flexible enough to allow correct movement.

The rolling motion of the front from side to side is one form of lateral instability and is most often seen in a dog with a shortened upper arm. This dog cannot get its legs underneath its body. A dog with a wide front, and a rear that correctly reaches underneath the body toward the centerline, causes the front to roll back and forth. The same force that causes a good Bulldog (and Pekingese) to exhibit the desired roll in the front is a fault in almost all other breeds.

Bulldog: “The style and carriage are peculiar, his gait being a loose-jointed, shuffling, sidewise motion, giving the characteristic ‘roll.’ The action must, however, be unrestrained, free and vigorous.”

Pekingese: “It is unhurried, dignified, free and strong, with a slight roll over the shoulders. This motion is smooth and effortless and is as free as possible from bouncing, prancing or jarring. The rolling gait results from a combination of the bowed forelegs, well laid back shoulders, full broad chest and narrow light rear, all of which produce adequate reach and moderate drive.”

Lateral instability can also be evident when the dog’s body sways from side to side. This may be due to a too long, slack loin or poor muscle development throughout the dog’s body. Whatever the cause, the greater the roll in the dog the more energy the dog expends to overcome the rolling motion and move forward. Although the skeleton is the framework and support for the dog, without well-toned muscles to make the skeleton move there can be no locomotion.

The dog has a center of gravity, and in most breeds, the legs converge toward the centerline of the body when in motion—the faster the dog trots, the closer to the centerline the legs move. This reduces lateral movement (rocking and rolling from side to side). In those wide-fronted breeds with a lower center of gravity, a narrower skeletal rear structure helps to give stability to the wide stance in front. (Think of the stability of a three-legged stool.) This particular structure also keeps the legs clear of each other when in motion, preventing the feet from interfering with each other.

Some breeds double track and do so with a wider front and rear stance. This gives stability to the movement, with no rolling motion evident. These dogs generally have a wider skeletal structure, a broad front, a broad abdominal structure, and a well-developed loin. This combination provides more rigidity, making ease of lateral and vertical movement more difficult.

In addition to this wide double track, some breeds call for a more “pendulum swing” front action by carrying the forelimbs straight forward and parallel to each other, with a matching action in the rear. (Smooth Fox Terrier: The Terrier’s legs should be carried straight forward while traveling, the forelegs hanging perpendicular and swinging parallel with the sides, like the pendulum of a clock. The principal propulsive power is furnished by the hind legs, perfection of action being found in the Terrier possessing long thighs and muscular second thighs well bent at the stifles, which admit of a strong forward thrust or “snatch” of the hocks. When approaching, the forelegs should form a continuation of the straight line of the front, the feet being the same distance apart as the elbows.)

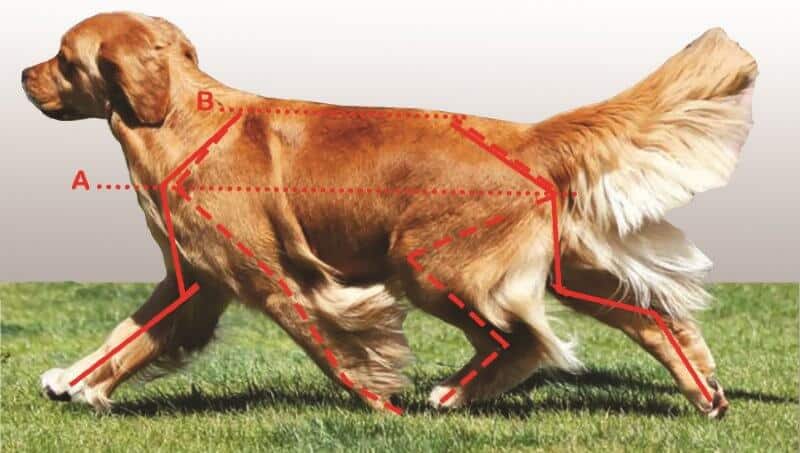

You should train your eye to watch the dog’s forward motion by keeping an eye on Lines A and B. (See Figure 3.) Line A intersects both the angles of the shoulder and upper arm, and the hip and the femur, and is parallel to the ground. Over these two points, the body is propelled by the rear quarters. Line B is drawn across the tip of the pelvis and parallels the spine. Line B is also parallel to the ground. Using Line B as a reference provides a guideline for the motion of the back, and the slope of the pelvis and croup can be assessed.

These horizontal Lines A & B will remain parallel to the ground when the dog is in motion, though they will be lifted slightly as the body’s weight is transferred from the pad to the toe pads. The dog shown above displays lovely balanced angulation, fore and aft. She is balanced in all of her parts, with all of her major bones (scapula, humerus, pelvis, and femur) of approximately the same size. She maintains her shape and form, both standing and in motion.

As the dog moves forward, the head and neck are thrust forward and down, over the swinging forelegs, to maintain kinetic balance. When the dog begins moving, the withers drop a bit in relation to the movement of the shoulders, and the topline remains level. However, in some breeds and in well-exercised dogs in good muscular condition, a slight curve may form over the lumbar area, which aids in propulsion. As the dog moves forward, the topline changes constantly; however, throughout the entire cycle of a dog’s stride, Lines A and B should remain parallel to the ground.

The position and carriage of the dog’s head, neck, and torso can have a positive or negative effect on the efficiency of movement and on the conservation or loss of energy when the dog is in motion. This can also affect the unique rhythm and speed of the gait and the dog’s ability to perform the work it was bred to do.

It is challenging to portray side gait in photos and illustrations, especially the movements that can happen along the topline. To fully understand the topline’s action, you should watch as many dogs as possible in slow motion. With the advent of such good cameras in cell phones (some even equipped with slow-motion settings) it is easier than ever to capture dogs in motion digitally.

*I have addressed this in previous articles, but a 90-degree angle has been proven to occur only in dwarf breeds. I will not argue this point here, as way too many standards put this forward as the ideal for their breed. We can determine the dog’s angulation by palpating certain “landmarks,” such as the spine of the scapula to the point of the shoulder and then to the elbow of the dog. We then check the rear by locating the landmarks that can be palpated there. When examined, most breeds which call for a 45-degree layback and 90-degree angle seem to have a 45-degree layback and a 90-degree articulation with the dog’s upper arm or upper thigh.

If you have any comments or questions, or want to book a seminar, contact me at jimanie@welshcorgi.com.