Home » Breed-Specific Pain Sensitivity in Dogs

Is a Chihuahua tougher than a Rottweiler?

Is a Husky more sensitive than a Boston Terrier?

Many people have opinions on these types of breed-related differences. In a survey of over 1,000 veterinarians, 95 percent of respondents agreed that dog breeds differ in pain sensitivity. That sentiment was similarly reflected in a survey of the general public (also more than 1,000 respondents). However, veterinarians ranked breeds differently than the public with regard to pain sensitivity.

Until recently, there was no scientific evidence that dog breeds differ in their pain sensitivity. However, a team of AKC Canine Health Foundation (CHF) funded investigators at North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine have published results from their groundbreaking study which may radically change how we understand canine pain. (CHF Grant 02797: Do Dog Breeds Differ in Pain Sensitivity?)

The existence of differences in pain sensitivity between different dog breeds would significantly impact the diagnosis and management of canine pain. If there are physiologic differences in how dog breeds experience pain, what are the mechanisms and/or genetics involved? Can we modify pain management protocols to target these individual mechanisms and therefore improve pain relief and minimize unwanted side effects?

If physiologic differences in pain sensitivity between different dog breeds do NOT exist, do our human beliefs about breed behavior or temperament still influence how we recognize and treat pain in individual dogs? Such false beliefs by owners or veterinary professionals could be detrimental to our canine friends, as dogs of breeds thought to be “tough” may not receive appropriate treatment for their pain.

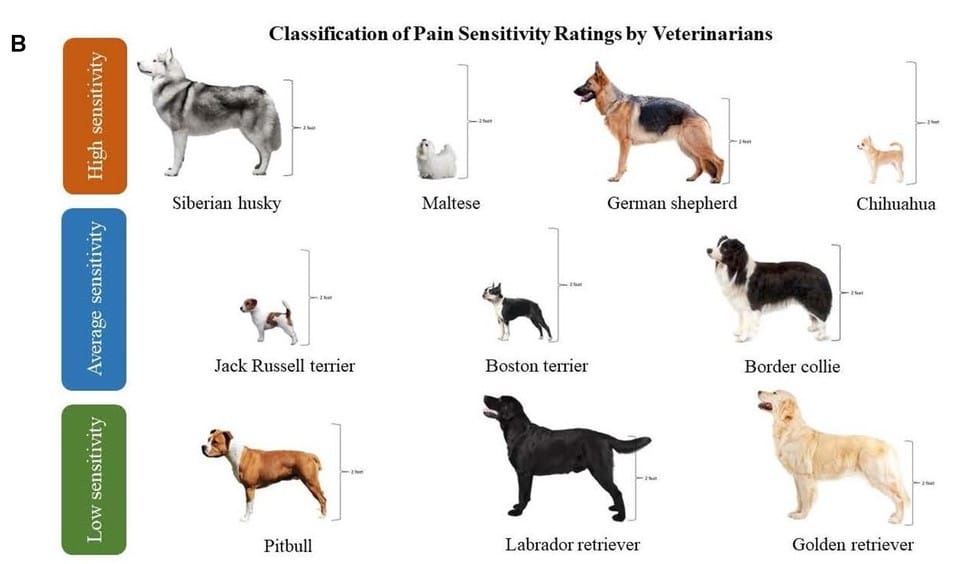

CHF-funded researchers set out to answer this important question: Do dog breeds differ in pain sensitivity? For this study, 149 client-owned dogs representing ten breeds or breed types (see Figure 1B) were tested using quantitative sensory testing (QST). In addition, their owners completed questionnaires, and behavioral tests were conducted.

QST methods are non-invasive, semi-objective tests used to measure the nervous system’s response to a standardized stimulus in a laboratory setting. A noxious stimulus is applied (such as mechanical pressure or hot/cold temperature), the sensation is detected by pain receptors and relayed to the central nervous system, and the subject indicates discomfort. Two mechanical pressure tests and one thermal test (heat) were applied to the carpus (front leg) of dogs participating in this study. Humans can verbally express their discomfort. For this study, investigators assumed discomfort and removed the stimulus whenever the dogs pulled their leg away, vocalized, stopped panting, licked their lips, and/or looked at the stimulus.

Since investigators had to use a behavioral response to indicate pain sensation in dogs, they also completed some tests of emotional reactivity to see if individual behavioral differences influenced the QST measurements. They timed how long it took each dog to approach a novel object (a mechanical monkey toy) and scored each dog’s initial response and approach to a disgruntled stranger.

QST testing revealed breed differences in pain sensitivity thresholds. While there were also breed differences in emotional reactivity, the pain sensitivity differences remained, even after accounting for reactivity. Therefore, behavioral differences alone were not sufficient to explain the pain sensitivity variations.

Veterinarian pain sensitivity rankings did not match those found on QST testing. However, they did correlate with how dogs approached the disgruntled stranger. This test measured fear and anxiety that could be experienced separate from pain at the veterinary clinic. Breeds that were reported as more sensitive to pain were those that were more hesitant to approach the disgruntled stranger. So, perhaps a dog’s initial interaction with the veterinary team influences the team’s beliefs about breed-specific pain sensitivity?

Results from this study have profound implications for recognizing and treating pain in dogs. QST results, from the largest group of dogs studied to date, demonstrated breed-specific pain sensitivity thresholds independent of sex or behavioral reactivity. Scientists can now explore the genetic and physiologic differences that explain breed-specific mechanisms of canine pain and use them to develop better diagnostic and treatment tools. Future studies evaluating the efficacy of medications or tools for canine pain relief must involve dogs of various breeds in their study design.

It will also be helpful to explore how, when, and why veterinarians develop their beliefs about breed differences in pain sensitivity. Veterinary professionals must be educated on physiologic and behavioral differences between dog breeds and how to best manage these unique but inter-related traits.

As the science of canine pain management continues to advance, CHF is proud to fund groundbreaking studies such as this to help improve the recognition and treatment of pain and other diseases in the dogs we love. Learn more about this important research here.