Home » Croup And Tail

Croup And Tail | Form follows function. When one delves into the nuance of one part of a dog’s body, it is amazing how complex what seems to be a simple anatomical part can be. It seems there are as many differing types of tails as there are breeds. Bobtail, bushy, curled, gay, docked, otter, plumed, ringed, screwed, snap, squirrel, teapot handle, wheel, rat, saber, sickle, terrier, flag, tapered, rocker, bent, clamped, kinked, crooked, half moon, knotted, twisted—and these were just through the standards of the first four Groups! Luckily for us the normal mechanics are basically the same for any breed, so that is what we will discuss today.

The Croup

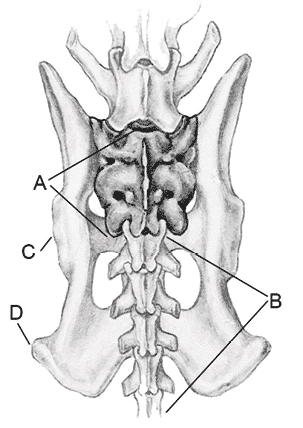

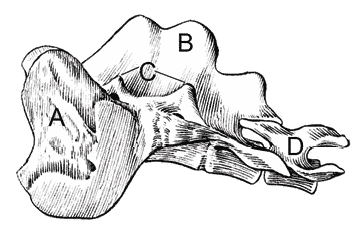

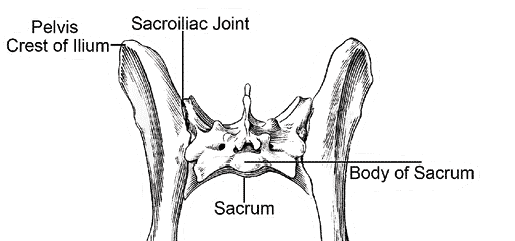

The three fused sacral vertebrae (see Figure 1. A–Sacrum) and the first four-to-five tail vertebrae (see Figure 1. B–Coccygeal Vertebrae) form the muscular area just above and around the set-on of the tail, which is defined as the croup. This group forms a slightly curved area, which is easily found upon physical examination (see Figure 2. Sacrum Side View). The structure of the sacrum (the three fused vertebrae) works as one unit, as there is no movement possible between them. The sacrum forms the anchor for the hind limb assembly where the transverse processes (the wings) of the sacrum join to the pelvis via a cartilaginous joint on both sides (see Figure 3). This very firm joining allows the direct transfer of the drive generated by the hind limbs to the spine (vertebral column).

Whereas the angulation of the croup depends upon the curve of the sacral and tail vertebrae, the angulation of the pelvis depends upon the angulation formed at the sacroiliac joints, where the sacrum articulates with the iliac of the pelvis.

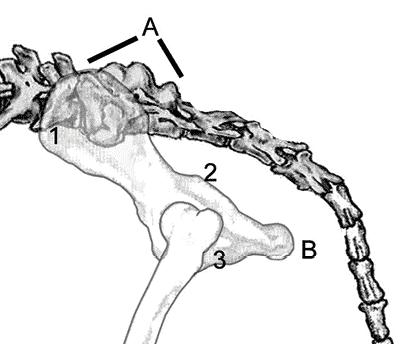

The function of the croup is to determine the set-on of the tail. The sacrum (sacral vertebrae) and the first several coccygeal (tail) vertebrae form the croup (see Figure 4 A). The angulation of the croup determines the tail set. If the croup is flat (horizontal) or level, the tail set will be high. If the croup is gently rounded, it becomes a continuation of the backline and the tail usually continues on the level of the spine, carried horizontally to the ground. If the croup is angled downward, the tail set will be low. The steeper the downward angle, the lower the tail set will be on the dog. The angulation of the croup is entirely dependent upon the curvature of the individual sacral and tail vertebrae.

Whereas the angulation of the croup depends upon the curve of the sacral and tail vertebrae, the angulation of the pelvis depends upon the angulation formed at the sacroiliac joints, where the sacrum articulates with the iliac of the pelvis. The pelvic girdle is formed by three primary, symmetrical bone pairs. On each side are (1) the ilium, (2) the ischium, and (3) the pubis bones (see Figure 4). The pelvic bones are joined directly to the three fused sacrum vertebrae by the sacroiliac joint. The angle in which the pairs of bones are attached to the sacrum is called the pelvic girdle slope. This angle varies from dog to dog. It is very important to know that the angulation of the croup and the angulation of the pelvis are INDEPENDENT of each other. Most often, the angles of the croup and pelvis are similar—a dog with a flat croup most often tends to also have a flat pelvis. But it is also possible for a dog to have a flat croup with a high tail set, and yet have a steep pelvis. This actually occurs quite frequently in my breed, the Pembroke Welsh Corgi, with its flat croup and high tail set, and yet the pelvis is steep and therefore, in motion, the dog cannot follow through behind.

The Tail

The tail is formed by a line of coccygeal vertebrae, usually twenty in number, which gradually become smaller toward the end of the tail. The first vertebra of the tail is about as wide as it is long. From this vertebra, the body of each following vertebra gradually lengthens to about the middle of the tail, and then the following vertebrae shorten toward the end of the tail.

As to the function of the tail, one may often look to the tail to determine the mood of the dog; happy, aggressive, stressed, etc. Dogs communicate with body language and the tail is no exception. A tail held high and wagging back and forth usually means a happy dog. A low, wagging tail may mean the dog is insecure or worried. A tail held horizontally to the ground may depict interest in something, and a tucked tail may mean the dog is unsure of the situation, is frightened, or is indicating submission. A dog with a tail held upright and rigid may be feeling challenged or threatened.

Not only does the dog use his tail to demonstrate his feelings, the tail is also used to spread the dog’s personal scent wherever he has been. Each dog has his own unique scent excreted from the anal glands, which can be widely spread by the motion (wagging) of the tail. The tail may also be used as a counterbalance to the weight of their body when in motion. Many dogs learn to use the tail to do just that in tight turns or when crossing narrow areas when working in search and rescue or competing in agility. Many breeds seem to be using their tail as a rudder, especially when working in water retrieving—whether it be waterfowl or bumpers. When watching the sighthounds running down the lure, it is often a lovely sight to see a long tail streaming out behind the dog. However, having lived with a tailless breed for over 45 years, I have never seen a Corgi suffer from the lack of a tail when working livestock or zipping around an agility arena—or even when swimming. I believe that any dog, even if born with a tail, can learn to adjust without one.

The many muscles and nerves associated with the tail of the dog are also associated with the rectum, the anus, and the pelvic diaphragm, and they contribute to bowel control and movement. So, there you have it. The tail is the end of this tale!

If you have any comments or questions, or to schedule a seminar on structure and movement, contact me via jimanie@welshcorgi.com.