Home » Form Follows Function – Reach & Layback

Form Follows Function: Reach & Layback

I am a big fan of the Facebook page “Canine Construction and Conformation,” administered by Australian fancier, Narelle Hammond of Australian Cattle Dog fame. So many thought-provoking questions and comments can be found there.

One thing that was brought up recently was the forequarter reach in the dog. Comments on the perplexities of the fore assembly of the canine were also a topic in a recent interview that I had given on Laura Reeves’ “Pure Dog Talk” podcast. Only so much can be accomplished through the written word without actual hands-on experience, but I do try my best to break things down so that it is easily understood even by the person involved in showing their first dog. I will attempt in the next several columns to get back to the basics and try to break down some of the things in the construction of the dog that seem to be the hardest areas to understand and are the questions that I have most often heard asked when discussing structure and movement.

The goal for the majority of breeds is for a dog to cover the most ground with the fewest number of steps, thus expending the least amount of energy to perform the job for which it was bred. What we are demonstrating here is the ideal movement expected in the “average dog” so that you may have a better understanding of the dynamics of canine gait. Once you understand this, then you can apply what you have learned here as to how your breed may or may not differ from what is presented concerning the average dog.

In Rachel Page Elliot’s study of canine gait, she evaluated the gait of the dog by x-raying moving dogs. With this study as well as the studies that have been done in years past by Curtis Brown, published in his book, Dog Locomotion and Gait Analysis in 1986, the position of the shoulder blade was more easily seen and evaluated. Curtis taught engineering classes at San Diego State and Purdue Universities and brought his engineering expertise to the fancy when he started showing dogs in 1938. Both of these renowned authors came to the conclusion that the “ideal” 90-degree angle (45 degrees to the horizontal) is incorrect in many breeds. Mrs. Elliott describes three types of forequarter structure based on the function of the breed. Brown comes up with the same basic ideas in his discussion of shoulder layback in the dog. Claudia Orlandi, Ph.D. summarizes the three categories well in her book, Practical Canine Anatomy & Movement. The 90-degree angulation called for in so many breeds is found in the achondroplastic breeds such as the Basset Hound and the Corgis. The shoulder blade and upper arm angulation are closer to 120 degrees in many of the retriever and herding breeds, and the breeds that are built for speed (sighthounds, etc.) have a shoulder-to-upper arm angle at approximately 130 degrees.

As a judge, I have found that because it is not possible to carry an x-ray machine in my back pocket (and unless height is a DQ in a breed it cannot be measured in the ring), what is left is the determination of structure through physical exam by determining the angulation from the landmarks that can be felt through the skin and musculature of the dog. These include the spine of the scapula, the point of the shoulder, the position of the elbow, etc. For this reason alone, I am including illustrations using a shoulder layback of 45 degrees, 30 degrees, and 20 degrees to determine the possible distance of the forward reach of the front foot of the dog.

Seeing movement is one of the things that is so hard to learn as well as teach, so let’s take a look at the forequarters of the dog once again and see if we can understand the limits imposed by the structure of the dog.

The forequarter assembly is composed of the scapula (shoulder blade) (Figure 1A) and the humerus (upper arm) (Figure 1B) which meet at the shoulder joint, often referred to as the point of the shoulder. Next in line is the elbow joint which joins the humerus to the radius and ulna (forearm) (Figure 1C&D). These two forearm bones are carried down to the carpals (pastern or wrist joint) (Figure 1E) and then on to the metacarpals (Figure 1F), the long bones that lead from the wrist joint to the toes of the dog (Figure 1G).

A closer look at the junction of the scapula to the humerus shows that the head of the humerus protrudes out somewhat as a knob of bone, known as the greater tubercle. (See Figure 2A.) This tubercle almost acts as a brake in that it helps to regulate the opening of the angle of the shoulder joint.

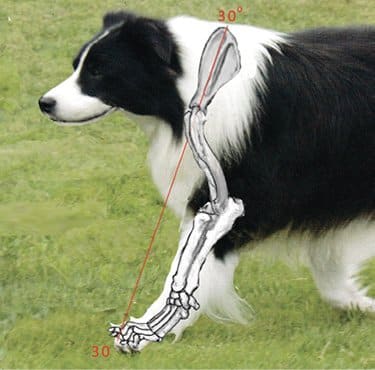

With a shoulder layback of 45 degrees to the horizontal, the reach of the dog should extend to a line drawn from the top of the scapula following the spine of the scapula to the ground. The more upright the shoulder becomes, the more the forelimb reach decreases. (See Figure 3.)

Any decrease in layback angulation moves the shoulder blade forward on the body of the dog. Even a move of 15 degrees less than the “ideal” of 45 degrees shortens the ability of the forward reach of the dog’s foot. (See Figure 4. The red line indicates where the toes of the dog will land when the layback is 30 degrees.)

When the shoulder blade is more upright, it not only drastically shortens the front reach of the forefoot, but the shoulder blade (by moving so far forward and upright) covers approximately one-third of the neck from view. This is not only due to the width of the shoulder blade but also due to the additional muscling on and around the blade. Every mammal has the same number of cervical (neck) vertebrae, which is seven. The neck is still there, but its usefulness is hampered in that it often affects the motion (or lack thereof) of the neck due to a change in the insertion and position of the muscles attached to it. (See Figure 5.)

While we are just looking at the layback of the shoulder in this exercise, you can also see that the more upright the shoulder blade is set onto the chest, the more of the neck it covers up, making the dog look as if the neck is shorter than it should be. Again, what we are discussing is the “ideal” placement of the shoulder blade—and yet we all know that this is extremely difficult to obtain in almost any breed and even more difficult to continually produce in a line of dogs. Even so, we should always strive for the “ideal” in our breeding programs and try to reach the “ideal” structure for our breed.

The goal for the majority of breeds is for a dog to cover the most ground with the fewest number of steps, thus expending the least amount of energy to perform the job for which it was bred. What we are demonstrating here is the ideal movement expected in the “average dog” so that you may have a better understanding of the dynamics of canine gait. Once you understand this, then you can apply what you have learned here as to how your breed may or may not differ from what is presented concerning the average dog.

Form Follows Function – Reach & Layback

For any questions or comments, contact me via email at jimanie@welshcorgi.com

By Stephanie Seabrook Hedgepath