Home » History of Standard Schnauzers in America

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – Out of the Mists of the Past

The bold, bewhiskered Standard Schnauzer is a high-spirited farm dog from the area around Bavaria and Württemberg in Germany. A breed of great antiquity, recognizable Standard Schnauzers appear in art as early as the 15th century. The Standard Schnauzer (Mittelschnauzer, or medium Schnauzer) is the prototype for two Schnauzer breeds developed much later—the late 19th century Miniature Schnauzer (Zwergschnauzer) and the mid-20th century Giant Schnauzer (Riesenschnauzer).

Schnauz, the German word for “snout,” colloquially means “moustache” or “whiskered snout.” The correct pronunciation of the “z” is “ts” (as in “Mozart”), but rarely is it heard in the US.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – Type and Temperament

Hallmarks of the breed (type) include a wiry, tight-fitting, pepper-and-salt or pure black coat with a soft, short undercoat of gray or fawn, or black for black coats; a robust, square-built frame; an elongated (rectangular) head furnished with arched eyebrows and bristly whiskers that frame oval, dark brown eyes gleaming with keen intelligence. A courageous “stand-firm-against-all-comers” attitude is part of Standard Schnauzer type as well—no wimps need apply here.

Speculations from the breed’s distant past say that the Schnauzer, then called the rough-coated Pinscher, originated by outcrossing the black German Poodle and the gray Wolfspitz with rough-coated Pinscher stock. The Pinscher element brings in the fawn-colored undercoats, and the Wolfspitz contributes the typical pepper-and-salt coat color with its harsh, wiry character.

Researchers at the University of California at Davis who have been studying the genetic inheritance of canine coats say that the arched eyebrows, bristly mustache and whiskers of the Schnauzer come from a dominant variant of the R-spondin-2 gene.

Acceptable SS coat colors (salt-and-pepper or solid black) result from the Agouti Signaling Protein (ASIP) gene. Salt-and-pepper coats express the dominant allele of the agouti gene. The dark coat has eumelanin pigment bands (black/brown presented as black), and the lighter coat has pheomelanin pigment bands (red/yellow faded to cream/white), both of which occur on the same hair shaft. These bands appear on the dog’s neck, shoulders, back, and rump, usually looking lighter on the chest, belly, and inside the legs. The recessive all-black Schnauzer coat originally resulted from mating two dogs carrying the ASIP gene’s recessive black allele; Schnauzers with this genotype will have a solid black base coat (no cream/white), which they pass on to all of their offspring.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – Purpose: Then and Now

In the Middle Ages, Schnauzers evolved in the fertile farm country of Bavaria when farmers and herders needed a reliable, fearless, all-purpose farm dog. Multitasking Schnauzers earned their keep as ratters, herders, guardians, and hunters:

The Schnauzer’s medium size fit perfectly into market carts without occupying space for wares. His over-large, sharp, gleaming teeth and his loud, deep, hearty bark—the bark of a much bigger dog—served as powerful deterrents to those who were up to no good. The Schnauzer is called “the dog with the human brain” by virtue of his intelligence and fearlessness.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – Early Art with Schnauzers

In Mecklenburg’s marketplace stands a statue dating back to the 14th century of a hunter with a Schnauzer crouching at his feet.

The breed is featured in several paintings by Albrecht Durer (1471–1528). He probably owned a Schnauzer himself—several of his paintings look like the same dog at different ages.

“Crown of Thorns,” a tapestry from 1501 by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553), contains a dog that looks like a Schnauzer.

In Stuttgart, a Schnauzer appears at the base of a sculpture called “Nachtwaechterbrunnen,” or in English, “The Night Watchman.” At the feet of this bronze watchman is what most Schnauzer fanciers believe is a Standard Schnauzer. Because it is dated 1620, viewers think the piece underscores the breed’s antiquity. However, this isn’t true, since the sculptor, Adolf Fremd, was born in 1853. The English painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), known for “The Grand Style” of portraiture, included in some paintings dogs that are Schnauzer-like, although most are Spaniels.

The most famous artwork claimed to include a Schnauzer is “The Night Watch” (1642, oil on canvas, 379.5 x 453.5 cm), arguably the best-known painting by Dutch master Rembrandt Harmanszoon van Rijn. Originally named “Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq,” it depicted a daytime assembly, but after layers of dirt and varnish had darkened the painting, it was renamed “The Night Watch.” In the painting’s lower right, to the left of the drummer, is a scruffy gray dog looking Schnauzer-like. Years ago at a SSCA National silent auction, I bought a digitally-remastered print of “The Night Watch” in which Willy Hakonsen (herself a van Rijn) replaced the gray dog with two groomed, show-ready Park Avenue Standard Schnauzers. My print hangs in our dog room; Rembrandt’s original hangs in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – Kennel Clubs & Registrations

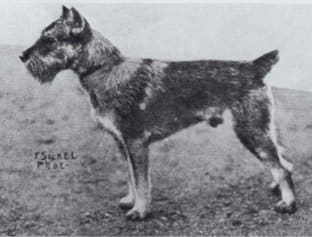

The first German Kennel Club (est. 1878) began holding regular dog shows in 1879. Wire-haired Pinschers were shown for the first time at the Third German International Show in Hanover (1879). Schnauzer, a dog from Wurttemburg Kennels in Leonburg, won first prize.

The American Kennel Club (est. 1884) and the Canadian Kennel Club (est. 1888) were not far behind their German brethren. The Sport of Purebred Dogs was off and running.

Prior to World War I, a small group of wealthy fanciers introduced Schnauzers to America. Together, they imported a number of top Schnauzers from Europe. Later (1922), Mrs. Nion Tucker bought Sgr. & Ch. Claus v Furstenwall for $7,000 in the currency of today.

During World War I, Standard Schnauzers served as dispatch carriers for the Red Cross and as guard dogs for the German Army. Both sides valued Standard Schnauzers for their unswerving loyalty, ability to follow orders, and intelligence to make independent decisions in the field when conditions warranted.

The first Standard Schnauzer (SS) registered in the United States was a dog named Norwood Victor (Schnauzer x Schnauzer), a salt-and-pepper male whelped in 1901 and listed by the AKC in 1904. From Norwood Kennels (Philadelphia), he won Open Dog First in New York and Philadelphia. Unconfirmed reports tell of Schnauzers shown in the Miscellaneous Class at Westminster and other shows in the late 1800s, but Victor was the first AKC-registered Standard Schnauzer shown.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – Early Sires & Dams

Four important matings are behind the modern Schnauzer, both in America and Europe, and most of today’s Schnauzers reach back to all four. The first was Sgr. Rex v Gunthersburg to Jette v d Enz, which produced Sgrs. Rigo v Schnauzerlust and Rex von Eglesee. The second mating was of Sgr. Prinz Schurl of Würzburg to Jette v d Enz, producing Hanna, Hexe, and Hummel v d Enz (1912). Next was Sgr. Prinz Schurl of Würzburg to Russi, producing Lore v Würzburg (1913). Last was Sgr. Prinz Schurl of Würzburg to Fanny 750, from which came Friederle (1914).

When serious efforts were made to establish Schnauzers in America (1924-1927), there were 61 males used at stud with 102 producing bitches. Of the males, 42 were sons or grandsons of three great sires: Ch. Sgr. Rigo v Schnauzerlust, Ch. Sgr. Rex von Eglesee, and Ch. Sgr. Mampe v Hohenstein. Fifty-two of the producing bitches were male-line descendents of these three influential males.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – American Firsts

The Schnauzer Club of America (first known as the Wire-Haired Pinscher Club) formed in 1925 for both Standard and Miniature Schnauzer fanciers. George D. Sloane was the club’s first President. Both breeds were exhibited as Working Dogs, and it was not unusual to see a Miniature take Best of Breed one week and a Standard win BOB the next, both often placing in the Working Group.

Schnauzers did well in the Working Group ring. In 1925, Group wins went to Chs. Clea Gamundia (first SS Group win on record), Bella v St. Johanntor, Fred Gamundia, Butz Saldan, and Claus v Furstenwall. (Claus was the first National Specialty winner). Fred, Claus, and Butz also went on to win Best in Show.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – A Working Dog

In 1926, Standard Schnauzers changed from the Working Group to the Terrier Group, but confusion in Schnauzer records show Schnauzers winning in both Groups. Why the Schnauzer moved from the Working to Terrier is an unsolved mystery. The move caused type changes in the breed that concerned breeders.

Not the least worrisome issue was that Terrier structure is significantly different from Working Dog structure, particularly shoulder assembly: the shoulder blade (scapula) and the upper arm (humerus) should be equal in length, and front angulation (the angle between the scapula and the humerus) is 45-degrees. This produces the prominent breastbone, or post sternum, located in the middle of the chest. In most Working, Sporting, and Herding Dogs, a protruding post sternum is desirable, indicating a large chest cavity that will allow the heart and lungs plenty of room to expand.

In Terriers, the humerus is shorter than the scapula, so front angulation is steeper and the chest is flatter as a result. Once a good front (defined as correct equality in length of scapula and humerus) is lost, it takes generations to repair the damage enough to get a decent front to return.

The biggest issue that Standard Schnauzer people would like to convey to judges is that the Standard Schanuzer is NOT a big Terrier and shouldn’t be judged as a Terrier. He’s a Working Dog and should be judged as such.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – A Major Conflict

In 1929, troubles were brewing in Schnauzerdom. The last Specialty was in 1927. Anti-cropping laws had become a major conflict in the Schnauzer Club of America (combined Miniatures and Standards). Entries at the shows were down. Those in power favored the English position against cropping ears, while many others, especially in the Midwest and in California, preferred the German tradition of cropping.

In 1931, the AKC canceled the wins of all cropped dogs born after September 1, 1929. Bad feelings ran rampant in the club, dividing it into two camps—those who preferred to crop and not show versus those who preferred to show and not crop. In 1933, a rule change allowed cropped and uncropped dogs to be shown equally in accordance with state laws, and titles were restored. But the bickering so unsettled exhibitors that the breed’s prominence in the Group and Best in Show rings was lost.

History of Standard Schnauzers in America – A Legacy Continues

A new day dawned in Schnauzerdom in 1933 when the AKC ruled that a specialty club could list only one breed, which brought about the dissolution of The Schnauzer Club and the formation of the Standard Schnauzer Club of America (SSCA) and the American Miniature Schnauzer Club. With the establishment of the separate breed clubs came separate registration as well. The Standard Schnauzer had finally had come into

its own.

The old Standard Schnauzers of half a millennium ago may have vanished into the mists of time, but their legacy continues to burn bright even today.