Home » In Search of the Last Shetland Sheepdog Breeders

In Search of the Last Shetland Sheepdog Breeders | An Adventurous Quest for the Origins of the Sheltie

After a journey to the Faroe Islands in 1998, I fell in love with the scenery offered by the Atlantic coastline and its islands. And as a dog lover, I decided to put Shetland on top of my list for any future exploration. Those islands are similar, though less dramatic, and I could turn my visit into a search for the last Shetland Sheepdogs, a breed that I like very much.

Flying to the Shetlands from Belgium is not that easy, as there are only flights from Aberdeen in the north of Scotland. So, I had to go via Prestwick with Ryanair, and from there to Glasgow airport to Aberdeen with British Airways. Flight schedules were not fitting nicely and I had to book a night in Prestwick. But this offered a way to climatize a little, though the weather was still good for September. I was only wondering if it would also be good enough in Shetland.

The climate in Shetland is not the sunniest, and the weather can easily ruin your whole trip. Winters can be harsh, mainly due to the winds that make the temperature feel a lot worse than it is, in fact. In reality, temperatures are rather moderate. Winters are rarely very cold, and summers are never very hot either. This is thanks to the milder influence of Gulf Streams. Anyway, you have to be prepared for every possible scenario, whether you go in summer or winter. The islands can be very foggy, sometimes for days in a row. And if there is no fog, most of the time this is thanks to the winds, which can blow you off the cliffs if you are not careful. But in general, the climate is much milder than certain people tend to believe, with an average of 2°C [35°F] in winter and 14°C [57°F] in summer. Locals say that you can have four seasons in one day.

Luck traveled with me and it all looked very promising when I arrived with a small propeller-operated aircraft at the airport of Sumburgh. It was sunny, and the contrast of the green rolling hills with the dark blue ocean (edged with foaming waves like lace bordering a royal blue robe) was all topped with a blue sky with bright white dots formed by the clouds. It was 4 p.m. and it would stay clear significantly longer than in Belgium, as the islands are situated as high as Bergen in Norway. I had booked a hotel for a night in “The Inn on the Hill” in Whiteness. This hotel is situated between Sumburgh and the capital, Lerwick, and its pub proved a popular meeting place for the locals from far around. While checking in, the hotel manager, who was also the barkeeper, inquired about the intentions of my visit to the islands, and I told him about my plans to search for the last breeders of the Shetland Sheepdog. He looked at me as if he’d never heard about a local breed named after the islands. I also asked him about the possibility to see the Northern Lights that could be seen from September on, if you were lucky. Some of the customers frowned at me and told me that they never saw it. But the manager contradicted them and claimed to have witnessed it a few times, but it was a matter of luck. After dinner, I mixed it up a little with some locals who were shooting pool, when suddenly the manager called me and asked me to come outside. “Sir, you wanted to see the Northern Lights, no? Well, come and see outside.” My heart bounced with enthusiasm. “I was taking some crates of beer out of my trunk and looked up to the sky and there it was,” he said, obviously sharing the same enthusiasm as me. I looked up to the sky as all the other locals followed me out too in disbelieve… and a minute later, we were all breathless and silent, overwhelmed by the spooky spectacle above our heads. Like endless stage curtains, the lights moved fluently, rolling like waves from green to yellow and to blue. The hotel manager closed down all the lights inside and outside on the parking lot, and the only thing we were missing was a Peer Gynt symphony playing in the background. This is one of the experiences that follows you for the rest of your days, like meeting whales or a group of elephants, or discovering a huge waterfall in a jungle. I felt so lucky that on my very first night on the islands I was experiencing something the majority of people would envy me for.

The next day, still excited about what I’d witnessed the previous night, I took off towards Baltasound on the island Unst, the highest situated island of the Shetlands. I was welcomed by my hosts, the Laird and his wife, and David and Jennifer Edmondston and their dog in their manor, Bunnest House, which looked even more promising than it appeared on the Internet. It was not the most strategic place to discover the islands, but it certainly offered the best way to experience them. The house was located near a bay, and it was rather misty when I arrived. After the customary introductions, I was shown my room. Apparently, the owners were descendants of a noble family with a tradition of exploring nature. On the walls of the stairway to the rooms were heads of tigers and antelopes, and on the floor was the skin and head of a bear. The walls of one of the rooms were completely decorated with prints, cut out from old magazines from the late 19th century. The bed, furniture, and bathroom were also in the very same style, as if I was thrown back into time. It was all very promising. It was the former children’s room that I was in, and the prints on the walls showed many lovely old pictures of children with dogs, the ones you could find on old tin biscuit boxes.

I was asked to be on time downstairs for dinner. As the Shetland Islands, and certainly the more remote places, don’t have restaurants at every corner, I wisely had chosen to rent a room all-in, and this proved to be a wise decision. The lady of the house was an excellent cook. After dinner, I had a lovely and entertaining evening around the old fireplace, talking with them along with another couple of residents about my plans for the coming days.

Hermaness National Nature Reserve was high on my list, and the Edmonstons offered to bring me to the entrance and stressed to me to be on time for dinner in the evening. The reserve was a project of my host’s forefather, Dr. L. Edmondston, a botanist who started to protect the Skuas (called Bronxies here), which were as good as extinct. This was back in 1831. Nowadays, around 100,000 seabirds are nesting here. It is now managed by the Scottish Natural Heritage, but the reserve is still the property of my host. I planned to go back walking, no need for them to come and pick me up. The reserve itself reveals a lot of the terrain that is common on these islands. Peat is omnipresent here. Grasslands on rocks are intersected by numerous little streams that sometimes, suddenly, disappear underground and reemerge often hundreds of meters away. If you wander around here without knowing the terrain, you can unknowingly end up in real danger and fall in an earth hole, right into such an underground stream. Those gaps can sometimes be deep too, and fatal for small dogs. Our small Shelties would probably take no such chance, and I start to doubt if the little companions, like we know them today, would make it here. As a working breed, I seriously have my doubts.

From west to east coasts, none of the islands are wider than 16km [9 miles] and it did not take very long before I ended up at the western cliffs of the reserve, the northernmost point of the UK. This stunning coastline offers spectacular cliffs where thousands of seabirds are nesting. Unfortunately, the cute and funny-looking Puffins were already gone. At a certain point, the cliffs were cut downwards, and I was treated to an enormous spectacle; thousands of Gannets were nesting, flying on and off to feed the chicks that were almost ready to fly out to the sea. The Hermaness Reserve hosts around 12,000 of these birds. I know how dangerous these places can be, but I could not help but go as near as was safe to the edge, taking my time to take some stunning pictures and enjoy the numerous birds sailing right in front of me, 170 meters [557 feet] high above the sea, including the spectacular flight of Skuas, the largest predatory gulls, attempting to steal away the catch of other Gulls and Gannets. Proof again that this is no place to bring around a pet Sheltie; not just for the cliffs, but also for the Skuas that would not hesitate to attack them, dive-bombing them, claws and beak open, if the dogs should wander near the nests hidden in the grass. It was such a fascinating sight that I forgot about the hour, and I suddenly realized that I had to hurry to be on time for dinner in the guesthouse. Suddenly, I started to realize that distances are very relative. Darkness started to fall and there was nobody to ask for the direction, or even a house or phone around. Mobile phones were not common then, and if so, it was not certain that there was any reach. Suddenly, a car stopped and the other guests of the home stepped out. My guests were very worried and had started a search. If they would not have found me, a search and rescue team would have been formed to look for me. I was very embarrassed to have caused all this trouble.

The next day, they took me to a place where there would be a chance to see sea otters in real life. It was a spot without cliffs, but instead, a small, golden sand beach. I say a “golden beach” and this it really was. Two giant rocks of silicate stood aside from the beach. They were losing flakes of silicate in the sand and these reflected their oily-colored shades. Mixed with the sand around, it looked like the beach was covered all over in golden glitter; a brilliant sight. The beach was covered all over with paw prints, ending in a hole nearby. Clearly, they were paw prints from a sea otter family, but unfortunately, no otters to be seen. I was then brought to another place for a nice walk along an elliptical bay. The starting point was at an old abandoned graveyard facing towards the sea. What an amazing last resting place, probably the most beautiful spot to be buried. I checked the names as far as they were readable, and it was fascinating to find out that it was merely people from around 1900 and somewhat later. But what surprised me most was that the average age of their death was very high, almost as high as nowadays, and this was unusual for that time. It’s probably proof that the harsh life on the islands was not necessarily life-shortening.

Walking along the cliffs, I met some cormorants. And while looking out over the water, I suddenly spotted a few porpoises. A little further, I heard the blowing of a whistle, and when I looked up, I saw a man on the hills, directing his Border Collie to collect the sheep that were all around. The dog was running high speed, and it was dawning on me again that this would not be the work for a Shetland Sheepdog. Fog surprised me again, suddenly, but this time I was right on time at the meeting point to be picked up again by my hosts.

The morning of my last day in Unst threatened to end, literally, into a misty cloud. But Mrs. Edmondston advised me to walk to a tiny reserve nearby… where a flower bloomed, unique in the world. I quickly found it. But not being a botanist, I did not know what to look for as there were many sorts of beautiful, tiny flowers all over. As the area was no larger than a football field, I stepped over the fence and continued for a walk. Mist and cliffs are never a good combination, and I was aware of the danger. My senses were on edge. Not far from the fence that I’d climbed over, I heard the sound of the sea, and so I slowed down my pace and approached carefully until the sight cleared in front of me and I found out that I was very near to the edge of a cliff. Curious to see how high I was, I layed down on my belly. At least 50 to 100 meters [164 to 328 feet] below me, three seals were lazily lying on a flat rock that stood out of the sea. Fascinating! A few photos later, I was on my way again along the edge of the cliffs. They were going down, but it was easy walking and the weather seemed to clear up a little. At some point, it felt like I was being watched, but I waved away the thought until I looked into the sea and spotted the head of a seal in the water, following me with prying eyes. How funny was that?! Suddenly, he was gone, and so I proceeded with my walk. Not far away, he was back, his piercing eyes pointed at me. He dove again, only to reappear a little further, but this time he must have called for his friends as I saw not one pair of eyes following my steps, but three! They followed like this for almost a kilometer long. What a lovely meeting!

The following morning, I had to head for my next place to stay and I had to be on time for the ferry. Once on the boat, I was looking for some change to pay for the transit. A nice man told me to say to the ferryman that I was with him in his car and I’d offered to come along with him by car as far as I needed. So, no need to pay for the ferry, as the tariff for a car includes its passengers. It was a rather long drive. Suddenly, he asked me if I already found traces of the Shetland Sheepdog. I was surprised by this and wondered how he could know about my intention to visit Shetland. “We met at the hotel… the Northern Lights… remember?” he asked. “I was there when you arrived, and in Shetland we don’t easily forget!” And from one moment to another, the long way didn’t seem so long anymore. He dropped me at my next B&B, about 10 minutes’ drive from his place on the Isle of Walls.

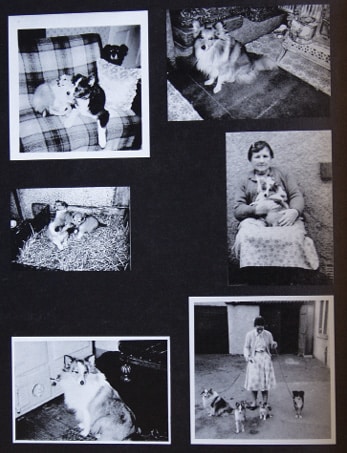

Mrs. Catherine Jamieson ran not just a B&B, but, with the help of the tourist office, I found out that she was the only breeder of Shelties left on the islands. My arrival was immediately reported by a little oversized Sheltie, or was it a rather small-sized Rough Collie? Anyway, the welcome was warm, the place very nice, but modern this time, and I was her only guest at the moment. I was late in the short summer season, as I was told. We immediately started to chat about the dogs, and she showed a lot of very interesting photos and very old postcards. She participated regularly in the annual small dog show, held as part of the Agricultural Fair.

The next day, I’d planned to hike around and discover the area. There were no restrictions to trespass the prairies and fields, provided you don’t leave any waste and you close the gates behind you. It was a lovely day and I wandered through the fields that were nothing like the steep hills and peat, pit-covered heather on Unst. There were many abandoned roofless cottages and barns around and I stumbled upon a carcass of a sheep, and a skull. I had to admit that this area would be more suited for a Sheltie, though it could never work as fast as a Border Collie. But on the other hand, these Shelties were a lot bigger than show-bred Shelties. Later in the evening, Mrs. Jamieson showed me some more photos, and on one of them, there was a more Border-Collie-like Sheltie, black and tan, that had won a medal. Mrs. Jamieson knew about the purpose of my trip, as I’d spoken to her on the phone when I booked my stay, and as a nice surprise, she had invited a few friends of hers who also owned Shelties, bred by her. When the bell rang and Mrs. Jamieson opened the door, a vivid conversation started not only among the ladies but also among the dogs. The house was full from one second to another. Unfortunately, the friend who was invited was speaking the local dialect, and even when she tried to speak proper English, or Scottish, it was very hard to understand a word. My recordings were undecipherable. Fortunately, Mrs.Jamieson later explained to me what the discussion was all about. According to her friend, the “Shetland Sheepdog” was the working dog, not the Sheltie as we know him now. The first dogs were the Shetland Collie, a type smaller than the Scottish Collie but larger than the Shetland Sheepdog, as we know it now. They could work fast, herding the sheep and bringing them into the farm. However, they had a shorter coat, one that was very water-resistant. Mrs. Jamieson was trying to convince her that the Sheltie, as a breed, is now called “Shetland Sheepdog,” hence the confusing discussion. And maybe she was right. The working dogs that I saw in the fields were all Border-Collie-like, far from the small Sheltie that we know from the shows. This became more clear to me later on my journey.

The next day, Mrs. Jamieson arranged for me to visit her parent’s farm where the sheep would be ear-marked that day. A black Border Collie was already very busy collecting the sheep according to his master’s commands, and not long after that, they were safely behind the fences while the dog kept focus on them like no other breed can focus on sheep. A chocolate-colored Border was also around, but obviously, he was older and no longer nervous—but still fit for the job. And there was a Sheltie around too, but he seemed more interested in herding the chicken instead of the sheep, as if he knew that herding the sheep was not his task. And suddenly, I realized the advantage of keeping a smaller, less nervous dog to keep an eye on the farm; killing vermin, barking when necessary, herding the chickens, pigs, and sheep on the farm, and being company to the family and the children, all while the larger “Shetland (Border) Collie” was the dog for the big and fast work in the prairies. It’s something you often saw on farms in the old days; a big dog outside, often chained, and a small companion dog inside the house.

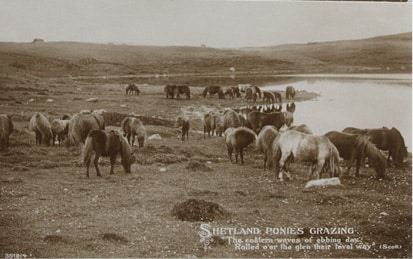

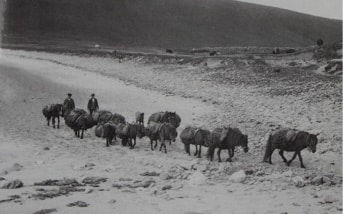

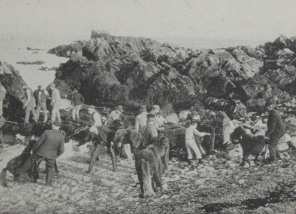

Mrs. Jamieson told me that the small Shelties you see nowadays were never typical. They have always been a bit larger. She showed me some old photos that she’d dug up from the drawer of her cupboard. “See how the Shetland Ponies were shipped to Scotland?” she asked. She showed me a photo of several ponies in a large rowboat, and one pony being pushed by the locals to step into the boat to be taken to a larger ship waiting further in the sea. The ponies didn’t look like the Shetland Ponies as we see them now; they were larger, but smaller than the Icelandic horse. “That’s the way they were transported to Scotland to work in the mines, pulling the wagons,” she said. “They had to be small, and the smallest types were most wanted. That’s why the farmers started to breed a smaller type too, and those are the ones that became popular and that we know now. The owners of the mines, mostly Scottish Lords, came over in the summer with their families, and those cute little ponies were, of course, the children’s favorites. And the poor farmers quickly learned how to earn a little extra money, breeding for small ponies.”

Mrs. Jamieson arranged a meeting for me on my very last day, right on my way to the airport. Her Shetland Sheepdog, was the first to welcome me when I rang the doorbell. According to British habits, tea was served. (Indeed, we were still in the UK.) Mrs. Irvine had already collected several items that she thought would draw my attention. Her Sheltie was smaller than the ones from Mrs. Jamieson, and more the type we see at shows over here. “I imported my Sheltie back from Scotland as there are no breeders here any longer,” Mrs. Irvine noted. “Mrs. Jamieson stopped breeding them too. So, my only remaining option, if I would like to get one, is to import one from abroad. They are a national heritage, and especially as my ancestors formed the Shetland Sheepdog as a breed as we know it now, I wanted to get on with the family tradition. But the ancestors of my dog go back to old breeding on the Shetland Islands.”

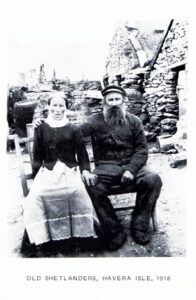

According to her, Scotland had more input in the breed than the Shetland Islands, when the lords (Lairds) from Scotland, who owned and exploited mines in Scotland and owned most of the land in Shetland, came over to spend the summer on the islands, around 1800, and brought their ladies and children along. On visiting the farms as landlords, they were often surprised by a summer litter of Shetland-Collie puppies, and like with the ponies, the smallest dogs were usually favorites to be picked out as summer pets for the children and taken back to Scotland. Once more, the smart farmers saw new opportunities to earn a little extra. The smaller they bred them, the better chance to sell

them for a good price, but probably, they were not very uniform as a breed. And once back in Scotland, they were probably crossed with the Rough Collies, hence new colors and the outlook of a miniature Collie. This makes sense. She showed me the first show trophies of the Shetland Sheepdog Club and an original printed copy of the first breed standard. Her grandfather was one of the founding members of the Shetland Collie club as it was called in 1908 when the club was founded. The photo of the dog in front of the carriage was the old type of Shetland Sheepdog, owned by Agnes Leask around 1940. (See black & white photo above.) The grandfather of this dog was a Shetland Collie and the grandmother was a Border Collie. The skull is broader and the nose shorter. An interesting detail is that Blue Merles were not recognized in Shetland.

After a quick photoshoot of her dog, it was time to leave the islands. On the plane back home, I recollected what I’d learned on this journey. The information was rather confusing. The original Shetland Sheepdog, or Shetland Collie, was probably a dog resembling the Border Collie more than he resembled the Scottish Collie, with varieties in size, the larger ones for working in the fields, the smaller ones kept on the farms, serving several purposes. It never mattered to a farmer how a dog looked. He only needed to be of use on the farm. That was his only reason to be kept alive in places and times when spoiling food was never a habit. The breed was fixed in Scotland by crossing the smallest examples, often brought to Scotland as pets for the families of Scottish landlords, with the Rough Collies from Scotland, hence the resemblance and colors and longer coats. The Shelties, or the small, original Shetland-Sheepdogs, were not meant to work outside the farms, at least not for collecting the sheep, because they were, in general, not adapted to the terrain, which is covered with pools and swamps, and intersected with numerous streams, often going underground with deep and dangerous potholes. And the islands are almost everywhere bordered by dangerous cliffs.

I might be wrong, of course, but I strongly believe that I am very close to how it went. I often hear the comments on the breed, when presented by the speakers in the main rings, that as everything on these islands is small due to the harsh winters and frequent storms, the Shetland Sheepdog, is small too, like the Shetland Ponies. Ridiculous! On the contrary, the winters are rather mild due to the warm Gulf Stream near the islands, and the winds… what do they have to do with it?! If so, why then are there no miniature rabbits and hares, or seabirds, or whatever other animals? Our modern Sheltie is just a fashion product of a local working farm dog, a breed shaped into a cute, intelligent, practical, and popular family dog with all the basic instincts specific to the Collie, but no longer adapted to the original hard work.

This adventurous quest for the origins of the Shetland Sheepdog dates back to September 2002. I have no idea if the people mentioned in this article are still alive, which I hope, or if now there are new local breeders on the islands.

I have fantastic memories of this trip and of the islands, and I can heartily recommend them.

Photos courtesy of Karl Donvil.