Home » Judging the Pointer

This article was originally published in Showsight Magazine, July 2013 issue.

Among all sporting dogs, the Pointer has achieved a place in history through the paintings of some of our most renowned artists, who depicted a dog of beauty and intensity working afield on upland game. Over the span of several centuries, volumes have been dedicated to his abilities in the field. The root of his origins is often debated among aficionados of sporting dogs. Was he a companion on hunting trips with the Egyptians 3000 years ago, etched in carvings on the tomb of Thebes? Did he stem from Spain with the influx of the Spanish pointer brought by troops into France and England in the 1600s? Is he, perhaps, just a jumble of genes through a bunch of disparate crosses from bloodhound to foxhound and ancient spaniel that produced, by luck of the cross, the breed we see today? There is considerable evidence in the bibliography to support an affirmative answer to the first two questions, and a resounding refutation of the last one. My advice, should you hold interest in the modern Pointer, is to read these historical accounts and weigh their evidence and the arguments in support of their positions carefully. In the final analysis, you be the judge.

The purpose of this article is to provide judges, who are at the forefront in the evaluation of the Pointer, a practical guide to ensure the evaluation of breeding stock is accomplished at its highest level of excellence. You should begin by reading the AKC Pointer standard, read it carefully, and read it often. Review the American Pointer Club Illustrated Standard. It is important to the evaluation process to translate the words of the standard into a mental image of the ideal specimen. Our responsibility as judges is to evaluate breeding stock with respect to the breed’s ideal. Among breed standards, the Pointer standard is not the most difficult to understand. In fact, it presents a very moderate view of a finely hewn sporting dog ready and willing to work afield. The connotations of what is stated in the standard relevant to the breed’s form and function, I detail in this article. I include several references to the Pointer’s field capabilities to draw a tight coupling between form and function.

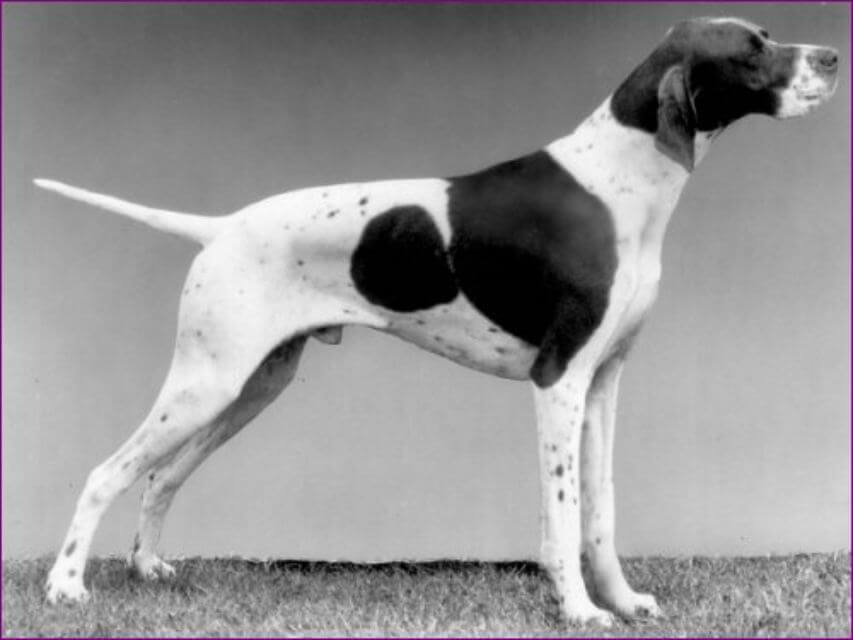

While attending the AKC Sporting Dog presentations last August, practically every breed presenter provided the audience with five key attributes of their breed that ensured thorough evaluation of breeding stock. For the Pointer, the five attributes that establish his true type are the head, front, feet, rear, and tail. They are placed in the order you judge a dog. The two attributes unique to the Pointer are his head and tail. To paraphrase William Arkwright, for a certificate of his heritage apply to the head, for a certificate of his blueblood apply to his tail.

Head (see Figures 1a, b, and c): I use the terms ‘classic dish’ as reference to the heads we find in paintings and older breed references that called for a concave nasal bone, which brings the nostrils to a point higher than the base of the stop, as in Figure 1a. Parallel planes are exhibited by the dog in Figure 1b. The nostrils should be large with considerable expanse as in Figure 1c. The stop should be pronounced with a rounded eye and proper placement to complement their dark brown color and intensity. The skull should be flat with a well-defined Occiput, and only as broad as the length of the muzzle from stop to nose.

To understand Pointer symmetry, it is important to understand several relative ratios that aid our subjective evaluation. Relative ratios have a tendency to get exaggerated if left unchecked, but the standard pulls us back to reality with the statement that the head should give the impression of length. Short-muzzled, rounded back skulls are not acceptable in the breed standard. The ear is triangular in shape, somewhat pointed at the tip, and thin in leather, carried at eye level or higher when excited. The ear should reach no further than to the lower jaw. A scissors or level bite is acceptable.

Front assembly: There is an old saying, ‘should he toe in he is out; should he toe out he is in.’ Toeing out is usually associated with young stock. They often grow out of this tendency by the time they reach 12-15 months of age. However, toeing in is often associated with problems in the humerus, rib spring, and front angulation. Proper muscle development and conditioning should be examined. (Refer to Figure 2 for a proper front view.) The width of the forechest is only as wide as is necessary to support a proper shoulder. (Refer to Figure 3 for a proper front assembly side view.) You must train your eye to visualize the layback of the scapula (remember to follow its mid-rib), and the angle formed with respect to the humerus or upper arm.

Most breed authorities concur with the observation the optimal angle of the scapula is 45 degrees, and the humerus should meet the scapula to form an angle of 90 degrees. In the ring, you often do not see these optimal angles. However, the elbow should set directly under a vertical line drawn from the point of the withers to the front pad. The front assembly is the most significant load-bearing structure in the Pointer. There should exist little doubt, the front is the most important structure of the dog’s skeleton. Refer to McDowell Lyon and Edward Gilbert for more critical analyses of dog structure. Both texts explore in detail the structural aspects and establish an excellent rationale for a proper Pointer front assembly and angulation.

Feet are oval, more to the hare in shape, never cat-footed; it is faulted in this breed. The Pointer foot is premier in its ability for work afield. The toes are well arched and accompanied by strong pads. In the field, a quick burst of speed, followed by abrupt turns, and pulling up abruptly to freeze in a statuesque point, hinge on a proper foot to support this action. We see a similar shaped foot in several hound breeds such as the Saluki, Afghan Hound, Greyhound, and Whippet. All these dogs are built for speed and quick turns. The pasterns should be finer in bone and slant slightly. The pastern serves as an additional shock absorption structure. Short, thick upright pasterns are to be avoided in this breed.

Tail carried level with the back, may be slightly elevated above the top line in the AKC standard, and lashed from side to side. It is thick at the root with the third caudal vertebra somewhat enlarged, then tapering to a fine point. Its length has been the object of considerable debate, but it should reach no further than to the hock. This is consistent with many sporting dog standards. Historically, the tail has been likened to a wasp or bee sting; however, the standard calls for neither.

In fact, historically, the documentation in many paintings illustrates a lovely pump handle tail, which follows a lazy S-curve. One cannot lose sight of the artistic works of Maud Earl, Deportes, Oudry, Blinks, Osthaus, and others, who documented the Pointer from the 17th century onward. The quality of the Pointer tail is one of the breed’s most important attributes, and exciting to watch its action when the Pointer is working on game. In the show ring, a tail should lash in small arcs. This is characteristic of the ideal tail action.

Rear assembly of the Pointer provides powerful propelling action with well-developed thighs. The upper thigh should not be weedy and overly refined. The hocks are short and strong, i.e., well let down. The Pointer rear angulation should balance with the front angulation. A well-angulated rear does not mean overly angulated. The standard calls for decided angulation as evidence of power and endurance. The judge should look for balance that supports proper reach and drive. Straight fronts and rears are to be avoided in the breed.

The five key attributes composed of head, front, feet, rear, and tail were presented. I proceed to add some additional details to the five key attributes. Soundness and temperament help round out the key components of the breed. As previously noted, the two attributes that speak to breed type are the head and tail, more than any other attribute of the breed. Selective breeding, to ensure good specimen replication, is paramount to guarantee long-term success for this breed’s type. The Pointer’s symmetry is a series of graceful curves. The curve comprised from the occiput, down the neck that should fit smoothly into the shoulders, across the short back and moderate length loin to finish at the tail should form a smooth curve. The underline curve begins at the point of the elbow that meets the brisket, follows on to the tuck-up, and flows across the thigh, upper thigh, and finishes at well-let-down hocks.

The curves represent an excellent test to assess how everything fits together, i.e., the Pointer’s overall image is reflected in these curves, the curves of symmetry. The Pointer should stand over ground: he is not a square dog. Relative ratios come into play again. From the point of shoulder to point of ischium it is slightly longer than height at the withers. The optimal inclination of the pelvis should be 30 degrees. The bone is oval and built for speed, never round as in the foxhound. The topline of the pointer should show a slight rise from the sacral vertebrae to the withers. It must not be flat, slack, or too long, as these traits will impede proper locomotion. The characteristic sporting dog formula of a short back and moderate length loin fits the Pointer’s conformation as well.

Soundness, in this article, references the merging of form and function. The Pointer should be moved on a loose lead to allow his head to come over his center of gravity. You should place equal emphasis on the up-and-back as well as movement in a circle. At the trot in the show ring, the head will come forward and slightly down when moved on a loose lead. The gait should be smooth and effortless, with feet traveling in low arcs for efficiency. Viewing movement from the side, a proper front assembly will permit the front foot to extend out as far as a vertical line through the tip of the muzzle. Feet and legs should move in unison, not crossing, paddling, winging, side-winding, pounding, or anything akin to hackney action. The latter is to be faulted. The pointer will tend to single track at the trot. This is an efficient and effective way to move and cover ground. In the field, the pointer moves rapidly with front legs and rear moving in unison like a hinge supported by a strong back, capable of considerable speed. The pointer is a very fast-running breed, well-muscled and athletic.

Temperament embodies the Pointer’s mental ability to demonstrate confidence and congenial behavior. He is very alert in all situations and keenly interested in anything that has wings. The Pointer is easily trained for work in the show ring and responds favorably to consistent training regimens. The socialization factor should begin at an early age, as the Pointer does not fare well if brought to dog shows with little or no prior experience. Young dogs are often a bit unruly, but judges should be patient to allow the handlers to bring out the best from their younger exhibits. International standards vary to some extent from the AKC standard. If you judge outside the US, you should be aware of the differences that may exist in the breed standards.

Some standards have size variations and emphasize the classic dish head. Most standard variations outside the US are associated with size limitations. I found the Italian standard to be most committed to relative ratios. The English standard provides for the tri-color: black & white with tan markings. In the AKC standard, the color is irrelevant, with a single comment that a good pointer cannot be a bad color. I have seen one liver tri-colored pointer in 48 years. Additional breed comments are detailed in the work of Solero8 and, to some extent, in Lola McDonald Daly’s book4. Solero’s book is written in Italian, and the illustrations are excellent. Enos Phillips2 has portraits of tri-colored Pointers in his book that date back several centuries. In breed seminars, I am often asked to answer the question of why there is such a disparity between the field pointer and show pointer.

The disparity is especially evident in the US. The answer lies in understanding the balance of form and function. With rare exception, those dedicated to field trials in the US emphasized the functional aspects of the breed at the expense of optimal structure. The field pointer evolved as a smaller aberration of the breed, with broader cathedral fronts and barrel ribs, shorter legs, and flagpole tails. The tail, designed perhaps by happenstance to illustrate some arcane association with desire and intensity, came in vogue as early as the mid-1930s. The late Robert Wehle6, whose pointers were a great success in field trials, created his own standard of the breed, which called for the vertical tail. A photograph of a pointer skeleton with the vertical tail appears in the book. The AKC pointers are excellent gundogs, where form and function have been emphasized without exempting the dog of its natural ability to hunt upland game. Different venues of competition have driven some to emphasize certain breed attributes over others. Hence, we have the divergence in breed type.

The standard exemplifies the importance of judging the entire animal, as a smooth, balanced dog is more desired. The formula I provided encapsulates the entire animal perspective in the evaluation of breeding stock. Several years ago, I had an opportunity to chat briefly with Ed Gilbert. I presented his book for an autograph. What Ed wrote are words I value: ‘Read, think and be challenged.’ This is practical advice for judges and breeders alike. Ongoing education is crucial to success as a breed evaluator. I find ringside observation of sporting dogs to be a valuable learning experience. Informal discussions with your peers at judges’ seminars are of additional value. I should add an additional observation—evaluation of breeding stock must begin with careful evaluation conducted by breeders whose intent is to present the pointer in the show ring or compete in the field.

The best years of the modern pointer lie ahead, with dedicated breeders and judges working together to ensure the breed’s quality remains intact. In reference to dog breeders, Robert Wehle6 said, ‘The dog breeders of today, then, are merely temporary custodians of the breeds that were handed down to us from the last generation of breeders and which we, in turn, shall hand on to the next generation.’ It is incumbent upon judges and breeders to ensure the preservation of the Pointer’s valuable and ancient heritage.