Home » Measuring Progress: Make a Lasting Impression

In the sport of dogs, there are many ways to gauge success. Rating systems and records are the most obvious means, as are titles that appear before and after a dog’s registered name. But before any dog can climb to the top of the heap, it must be able to make a good first – and lasting – impression.

Making an impression in the show ring, one that can be sustained for two and a half minutes and throughout a lengthy career, requires a dog and handler team that is instantly and continuously memorable. By standing out in a positive way—again and again and again—goals can be met and records may be broken. And although first impressions are essential, a successful campaign requires the development of genuine connections that leave an enduring mark in the minds (and hearts) of many, many judges.

As anyone who’s ever shown a dog successfully knows, first impressions are made through the use of hands that are steady, a voice that’s quiet, and body language that’s all but invisible. Also essential is a physical appearance that’s clean and neat. In the dog game, this is true for both exhibitors and their dogs as evidenced by the focus that’s given to grooming techniques and stylish show clothes. Appearance in the ring matters, and more than a few mediocre animals have achieved enviable records over the years owing to their remarkable presentation by skillful handlers who understand the importance of making a good impression. For all the purported emphasis on the evaluation of breeding stock, some judges remain easily swayed by a pretty picture and a dramatic performance.

To understand how impressions are made, it can be helpful to consider how visitors respond to artwork hanging on a museum wall. (Like dog show judges, museum goers have strong opinions.) For example, modern art can trigger emotions like confusion, frustration, and even anger. “My grandchild could paint that!” people will state emphatically. Antiquities, however, like those found in the British Museum, the State Hermitage, and the Musée du Louvre, are generally viewed with appreciation and enormous respect. The same is true of religious frescoes and altarpieces of the Italian Renaissance, though the works of Botticelli and da Vinci are equally revered for their cultural significance and spiritual inspiration as much as for their artistic appeal.

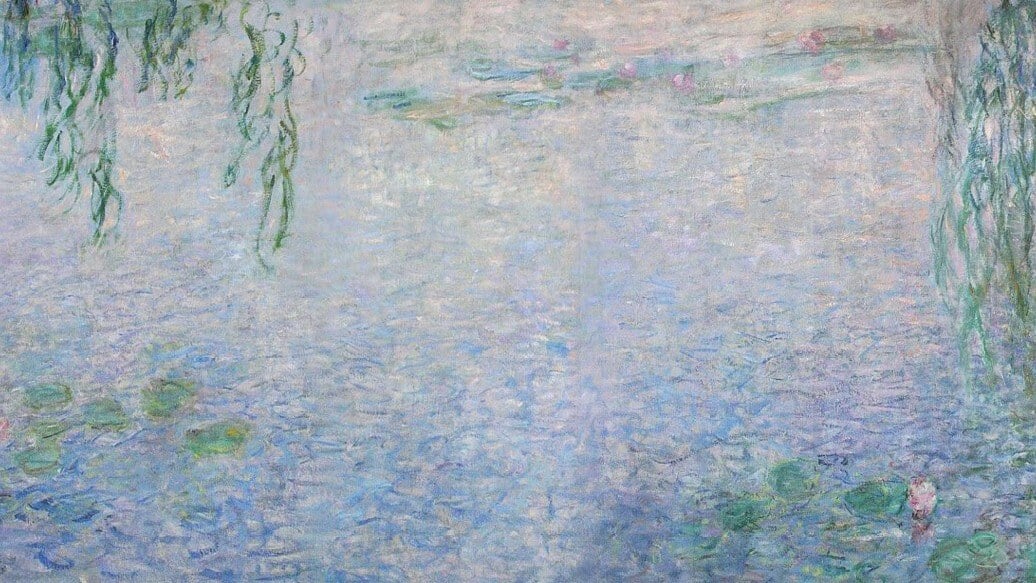

Impressions, favorable and otherwise, can be made wherever art installations exist, and perhaps no period is more universally embraced than the 19th century movement popularized by Renoir, Pizarro, Cézanne, and Monet – Impressionism. To appreciate the works of these and other Impressionist painters doesn’t require a great deal of intellectual thought, really. (They’re the pretty show dogs of any public-facing or private art collection.) Characterized by visible brushstrokes and an emphasis on the transformative power of natural light, these plein air compositions naturally elicit positive (and even affectionate) responses. Like a top-winning show dog, they make a good impression.

The works of Claude Monet, in particular, are especially moving. The paintings he created in his garden at Giverny in Normandy, France, are among his more impressive works. In particular, his 1899 waterlily series can have a transformative effect on viewers, as the serenity they evoke may be instantly felt. For many, the positive feelings can last a lifetime. And though widely accepted today, the paintings were initially criticized for being poorly defined and unfinished. Some critics even referred to their lack of realism as a mere “impression.” Public opinion, however, quickly raised their profile and paved the way for every art movement that followed, from Art Nouveau (Klimt) and Surrealism (Dalí) to Abstract Expressionism (Pollock) and Pop Art (Warhol).

What may be of interest to purebred dog fanciers is the fact that Monet didn’t simply paint what he saw. Like preservation breeders who create families of living, breathing works of art, his garden was his own vibrant creation. Giverny was developed in his mind alone and manifested with a singular vision. By virtue of Monet’s imagination and his sheer will, a vacant plot of land was transformed to become his muse. When he diverted water from an arm of the Epte River to establish a pond, water lilies became as precious as diamonds—or pedigreed dogs. Their likenesses, immortalized over the span of thirty years on approximately 250 canvases, have captured the hearts of millions for more than a century. And like the exceptional show dogs produced by modern masters through the years, they’ve left a lasting impression that endures to the present day.