Home » Measuring Proportions and Finding Landmarks | Part 3

The last article pointed out the landmarks of the dog’s neck, prosternum, chest, and shoulder assembly. We will now look at how to determine landmarks of the topline, underline, and rear assembly. Please note that the dogs used as our models are not “show” dogs but beloved pets. Getting them to stand for exam was rather amusing at times.

Immediately after you check the layback of the scapula and the angle of the front assembly, it is a simple thing to check the breadth of the dog’s rib cage and spring of rib. To do this, stand beside the dog with both hands’ palms down and thumbs close together at the tips. Place a hand on either side of the spine with the fingers laid along the rib cage, pointing down. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

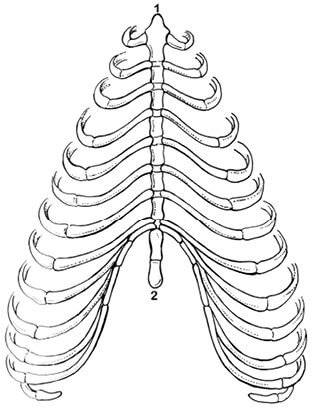

From this position, you have the hands placed on either side of the dog and can quickly feel how the ribs “spring” out from the spinal column, and then curve down and inward to attach to the sternum (breastbone) underneath the dog. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

In most breeds, the ribs flatten out somewhat behind the elbows so that the shoulder blade can rotate smoothly, back and forth, across the dog’s rib cage. A dog with too rounded ribs or with muscles that bulge and push the shoulder blade out (loaded shoulders) will cause a displacement of the elbow and a break in the column of support from the top of the shoulder to the foot.

The shape of the chest varies according to the function of the breed. Some breeds, such as the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, call for a more rounded ribcage. (“Rib cage barrel round and deep.”) Most call for an oval shape, but vary in the width of the chest. Examples are the Whippet (“Brisket very deep, reaching as nearly as possible to the point of the elbow. Ribs well sprung but with no suggestion of barrel shape.”) and the Lakeland Terrier (“The moderately narrow oval chest is deep, extending to the elbows. The ribs are well sprung and moderately rounded off the vertebrae.”) and the Rottweiler. (“The chest is roomy, broad and deep, reaching to elbow, with well pronounced forechest and well sprung, oval ribs.”)

A dog with a flattened rib cage is often called “slab-sided” and lacks spring of rib. On physical examination, your hands tend to go out from the spinal column only a short distance, and also tend to mostly go straight down instead of having an arch outward and then gently reaching back under the dog toward the sternum. A slab-sided rib cage inhibits the bellows motion vital to the expansion and contraction of the dog’s rib cage. (Remember that the ribs connect at the spine, and all but the last four ribs also connect at the bottom to the sternum or breastbone.)

The sternum may or may not protrude beyond the point of the shoulder (See Prosternum, Figure 5.1.) From that point, the sternum curves down and back between the dog’s front legs, toward the dog’s rear. (See Figure 5.2.) It is essential to ascertian where the sternum ends underneath the body (Figure 5.2) by physical examination. The sternum ends at the Xiphoid process (Figure 5.2), an important landmark to identify as it helps you to understand just how long (or short) the dog’s chest maybe. I know of no breed standard that considers a flat-ribbed (slab-sided) chest to be a virtue, as it would inhibit the dog’s ability to breathe.

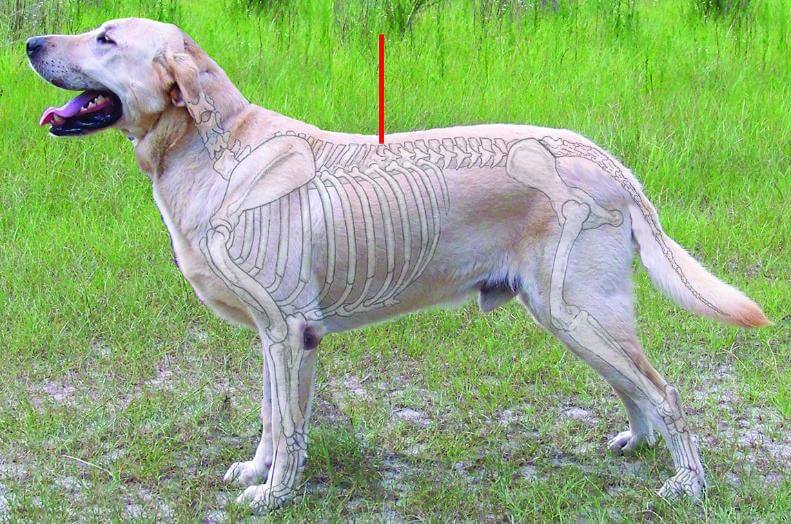

After checking rib spring and elbow position, next, run your hand along the dog’s back from the withers to the set-on of the tail. There is not much to feel when palpating the spine, mainly because much muscling is covering the bones. You might feel a slight “nick” (indicated by a vertical line on Figure 6) which is a landmark to designate where the direction of the vertebrae changes mid-back, but this is often difficult to find on a well-muscled dog. It is still a good idea to feel along the back of thedog to note any dips or bumps that can indicate the condition and muscle development of the dog. In very few breeds do you want to feel each of the vertebrae individually.

The spine includes the neck (cervical), body (thoracic), and loin (lumbar) vertebrae. (See Figure 6.) There are 13 thoracic vertebrae that provide support and a place for the attachment of the ribs, and many projections and planes at which the various muscles of the neck and back attach to the spine. The first nine thoracic vertebrae are considered the “withers” of the dog and are the point at which the highest point of the scapula is joined to the ribcage. The spine as a whole (starting at the neck) forms a very gentle “S” from the head to the tail—with the easily felt landmarks of the first several higher, longer thoracic vertebrae pointing toward the rear of the dog.

The last four thoracic vertebrae are more or less flat, forming the dog’s mid-back, and are relatively level. These four vertebrae also serve to carry ribs, but like the lumbar vertebrae (which do not attach to the rib cage) they allow for freer up-and-down movement. Next come the seven lumbar vertebrae that support and protect the abdominal organs, support the pelvis, and enable power transmission from the rear assembly to the rest of the dog. Unlike the thoracic vertebrae, the lumbar vertebrae point toward the head of the dog. The sacral vertebrae group attaches on either side to the pelvis, forming a firm union through which the forces generated from the hindquarters are transmitted to the spinal column.

In addition to feeling along the topline, you should also continue to the croup, to determine the set-on of the tail. (See Figure 7.) The croup is formed by the three fused sacral vertebrae and the first several tail (coccygeal) vertebrae, and together these form a slightly curved area that is easily felt. A dog with a high tail set will have a relatively flat croup, and the curve of the croup is more accentuated the lower the set-on of the tail.

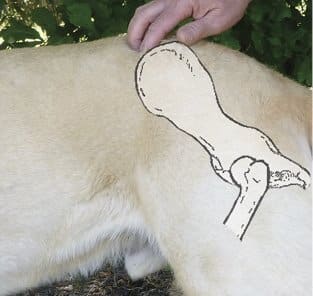

Next, we will check the length of the loin. It is relatively easy to find the landmark of the last floating rib on the side of the dog. (See Figure 8.)

From that point, you only have to slide your thumb over on the dog’s side to find the end of the loin, which stops at the beginning of the hindquarters; another fairly easily found landmark. (See Figure 9.)

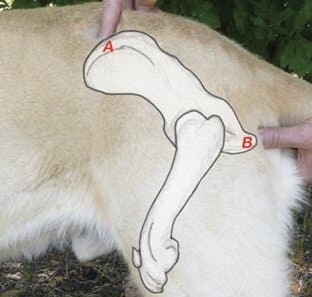

The next step is to ascertain the angle of the pelvis, which is harder to palpate than the much easierto feel spine of the scapula. Gently palpate down the spine until you can feel the landmark of the ridge of the pelvis. You may be able to feel along the side of the pelvis (ilium) up to our next landmark, the highest point of the pelvic bone (iliac crest). (See Figures 10 & 11.) By gentle palpation of this area, you will have a good idea of where the top of the bone is located.

To determine the angle at which the pelvic bone is set, you must try to locate the next landmark, the pin bone (ischial tuberosity). The pin bone landmark is easily palpated, except perhaps on a very well-muscled dog. It is one of the more important landmarks that can help us determine structure without radiographic examination of the rear assembly of the dog. (See Figures 12 & 13.)

The average dog’s pelvis angle is at 30 degrees to the ground. The slope of the pelvis determines the follow-through or backward extension of the hindfoot and the length of forward reach of the hind legs under the dog’s body. The angle of the croup determines the set-on of the tail. (See Figures 14 & 15.)

On a short-coated breed, the bend of stifle is easily seen. To determine the turn (bend) of stifle on a coated breed, run your hand down the forward edge of the leg from the top of the leg past the stifle, down to the junction with the hock. The hock is at the upper end of the rear pastern, between the hock joint and the foot.

The final determination to be made concerning the dog’s outline is the underline. In a short-coated breed, the depth of chest and its position relative to the elbow is easy to determine by visual exam. The elbow is a very easily found landmark in just about any breed. In a coated breed, however, youhave to use the palm of your flattened hand to move back the coat to see the position of the bottom of the chest (brisket or sternum) in relation to the elbow. (See Figure 16.) Most breed standards call for the elbow and the brisket to be at the same level. (See Figure 17.)

On a dwarf breed, the elbow naturally has to be positioned above the brisket, but the brisket should not be so low as to encroach upon the pastern area. (See Figure 18.) On this long-coated Pembroke (called a “fluffy” in the standard), the elbow is definitely above the brisket. (See Figure 19.)

If you have any questions or comments, or to schedule a seminar, you may contact me at jimanie@welshcorgi.com.

To purchase a copy of the DVD, “Structure and Movement in the Pembroke Welsh Corgi,” go to https://www.welshcorgi.com/DVD.html.

Measuring Proportions and Finding Landmarks – Part 3: Topline, Underline & Rear Assembly

By Stephanie Seabrook Hedgepath