Home » Origins and History of the Xoloitzcuintli

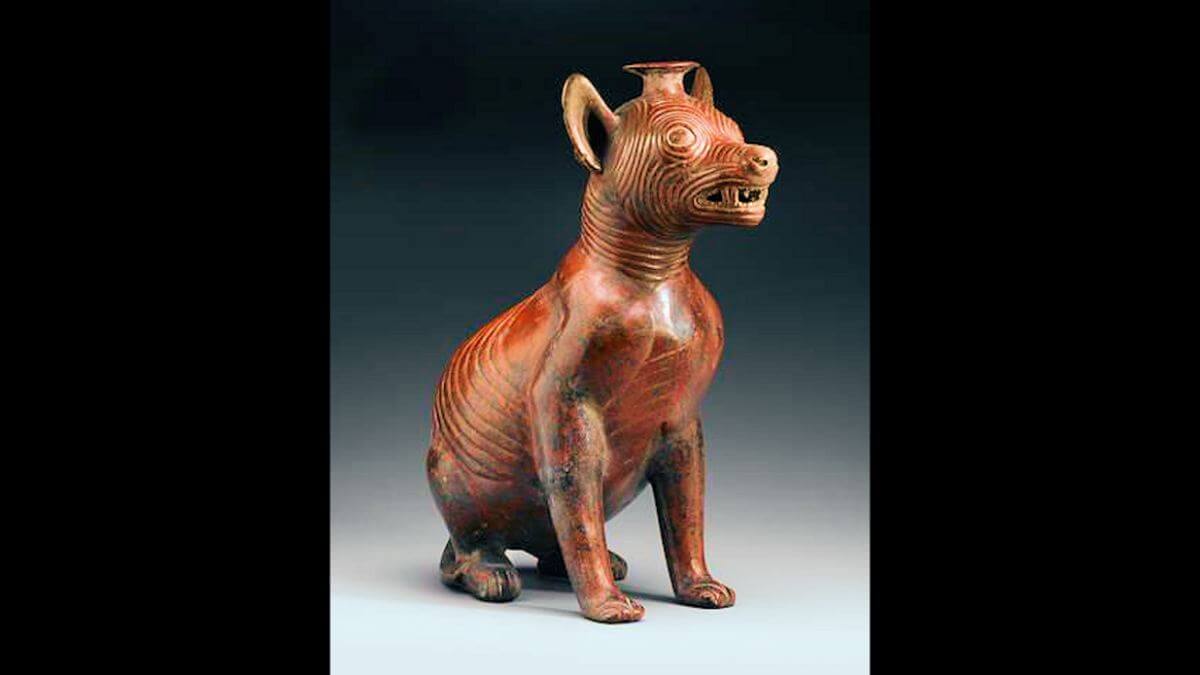

Clay Statues of Hairles Dogs have been found in the thousands in burial sites in Mexico. Highly collectible, these ancient artifacts illustrate the extraordinary importance that this dog held in ancient society. Columbus mentioned encountering strange hairless dogs in his 1492 New World journals.

The next account of the Xoloitzcuintle (“Mexican Hairless Dog”) is by the European Glover M. Allen in his Dogs of the American Aborigines, 1920, and seems to be that of Francisco Hernandez, (1514-1578):

“A dog of medium size, rather heavily built, and long bodied in proportion to its height; ears large and erect; tail thick, drooping or carried nearly straight behind; hair nearly absent except for a few coarse vibrissae and generally a sparse coating on the tail, particularly near the tip sometimes a tuft on the crown.”

“The first and largest of these American dogs is called Xoloitzcuintli. He is often three cubits long (18 inches); and what is remarkable, he is totally destitute of hair, and only covered with a soft, close skin marked with yellow and spots.”

The Xoloitzcuintli is now known to be one of the world’s oldest and rarest breeds, with statues identical to the hairless variety dating back over 3,000 years. These clay and ceramic effigies have been found in tombs of the Mayan, Colima, and Aztec Indians. Xolos were considered sacred dogs by the Aztecs (and also Toltecs, Mayans, and some other groups) because they believed the dogs were needed by their masters’ souls to help them safely through the underworld, and also, they were useful companion animals. According to Aztec mythology, the god of lightning and death, Xolotl, made the Xoloitzcuintle from a sliver of the Bone of Life from which all mankind was made. Xolotl gave this gift to man with the instruction to guard it with his life. In exchange, it would guide man through the dangers of Mictlan, the World of Death, toward the Evening Star in the Heavens. The Aztecs deeply revered the Xolo and believed the breed to have mystical healing abilities.

Indeed, the dog owes its name to the Aztecs, who named the breed after Xolotl. This root word was then co-joined with the word for dog, “itzcuintli,” to form the name Xoloitzcuintli (pronounced show-low-eet-squint-lee). For the Aztecs as well as several other pre-Columbian civilizations, the Xolo dog possessed not just healing properties for the physical body but also for the spirit. There were actual dogs buried alongside their caretakers, and statues of these dogs were placed in tombs to ritualistically serve the same purpose. The famous “Colima dog statues” are the premier examples of this.

Always prized for their loyalty, companionship, and intelligence, Xolos are also credited with curative and mystical powers. Because they were believed to be favored by the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, sacrifices of the dogs were sometimes dedicated to him. At one time, Xolos were prevalent throughout Mexico and large portions of Central and South America. Most likely, early forerunners of the Xolo originated as spontaneous hairless mutations of indigenous New World dogs. Hairlessness may have offered a survival advantage in these tropical regions. Indigenous peoples of these areas valued the Xolos for their loyalty, companionship, and intelligence, as well as their curative and mystical powers. In poor, rural areas, Xolos were eaten when other food was not available.

We include the following excerpts as being from a primary and important source.

“A Guide to Mexican Mammals and Reptiles”

by N. Pelham Wright, F.Z.S. (Published in 1965 in Mexico)

“…there are two types, or breeds, of Dog that have evolved in Mexico and are to be regarded as typically Mexican. It so happens, moreover, that neither is fully understood, and that a considerable amount of nonsense has been written about both.”

“…the other is the Xoloitzcuintli, an animal without hair on its body that in hardly any way resembles the chihuahueno. Seemingly, there is confusion with respect to not only the names of these animals, but also their origin and history…”

“…The second Dog–more important and much more typical of Mexico–is called xoloitzcuintli, sometimes now abbreviated to Sholo… Together with other undefined types of Dogs, the sholo was the first domestic animal in North America. Its forebears, already with some unexplained biological tendency toward nudity, must have accompanied early man from Eastern Asia across the Bering Straits. Its nearest relative is another form of naked Dog formerly known in Manchuria, and possibly still present there. Zoologists like Brehm complicated the issue of its classification by giving it Latin names such as Canis caribbaeus, in Yucatan, as though it were a natural, wild species, whereas it was never a wild animal but merely an unconventional form of Canis domesticus.”

“More recently, zoologists have stated categorically that there has been no wild canine in America which could have been the progenitor of any domestic Dog. This is tantamount to saying that all Dogs found with American Indians when the Europeans arrived must have been descendants of those brought from Asia by prehistoric immigrants. There is a wealth of evidence that, before the Conquest, the Indians in Mexico held the sholo in great esteem; that it had a religious significance, was used medicinally, and even eaten; and that efforts were made, with the help of a depilatory unguent, the recipe for which has been lost, to maintain its nude state. The Nahuatl name xoloitzcuintli means ‘he who snatches his food with teeth sharp as obsidian (i.e., Dog), and who is the representative of the god Xolotl.’ This deity was the god of twins and monsters, being himself the twin brother of Quetzalcoatl, god of life and civilization.”

“The animal’s ancient religious role is illustrated by the belief, widespread even today amongst certain rural groups in Mexico, that the dead need to be ferried across at least one subterranean infernal river, before their souls can reach ‘the promised land.’ Only black Dogs were thought to be able to do this, and to save their masters from the fiendish crocodiles encountered on the journey. Therefore, the Dog of the deceased was killed and buried with him. The sholo, normally black or at least dark gray, can be assumed to have been the type of black Dog favored for this ferrying operation.”

“Medicinally, the sholo’s value is logical in the extreme. Certain simple ailments can be alleviated by the use of a hot-water bottle. The hot, naked—and consequently flealess—body of a xoloitzcuintli makes a fine substitute and, even today, countrywomen in Sinaloa, when they feel indisposed, go to bed with a sholo to warm their stomachs. Among older people in the Balsas River Valley, state of Guerrero, it is believed that possession of such a Dog protects them from colds and other ailments.”

“Early Spanish historians reported that dog flesh was relished by the Indians, who considered it a great delicacy. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, for one, mentioned hairless Dogs among the innumerable exotic food items the conquerors found for sale in the fabulous marketplace of Tlatelolco. It is even recorded that, in the 16th century, many Spaniards acquired a taste for dog flesh. The sholo is usually called pelon mexicano in popular parlance. The Mexican Kennel Club finally adopted the present name, in complex circumstances… It is not identical with the animal called Mexican Hairless in the United States, which was probably never an established breed, but a creature of unstable form, bearing little resemblance to the traditional xoloitzcuintli.”

“…I have had correspondence with a geneticist which undoubtedly has a bearing on this animal’s curious characteristics, even though further study of the matter may indicate some local deviation from the law concerning hairlessness that has been expounded by certain geneticists.”

“In brief, the law is that there is a dominant gene for hairlessness, and that all hairless dogs have one, as well as a counterpart gene, for a normal coat.”

“Litters from hairless matings allegedly consist of 25 percent with normal coats (homozygous), 50 percent hairless (heterozygous), and 25 percent still-born, the latter having inherited the dominant gene from both parents. It is stated that selective breeding cannot change these proportions, with the result that it will, clearly, never be possible to regard hairless dogs as genetically stable, for “throwbacks” with normal coats will persist forever…”

“…only a conscientious long-term study of the matter appears likely to determine whether or not the xoloitzcuintli constitutes an exception to the law.” (N. B. recent scientific studies have confirmed that the double dominant hairless gene (HH) is, in fact, embryolethel, or deadly. All species, i.e., hairless mice, moles, cats, etc. appear to be thus affected.)

“In 1955 I was invited by the Mexican Kennel Club to take steps to preserve the sholo which, it was suspected, was threatened with near extinction. At that time, only one Dog that was felt to conform to type was registered with the Club. Now, ten years later, more than 70 specimens are registered. A detailed standard for the breed was evolved and published.”

“Elsewhere I have reported on an expedition to a certain village in a tropical area of Guerrero which brought back to the capital the first good specimens for breeding purposes. Later, I returned to the village for more animals, and the majority of the registered sholos living today, at least those belonging to Dog fanciers, are descendants of the specimens I obtained from the Balsas River Valley in the 1950s.”

“The xoloitzcuintli is, indeed, a very unusual Dog, unique in many ways. It has three physical peculiarities that no biologist has yet explained: an almost invariable absence of teeth between the foremost molars and the incisors; a body temperature several degrees higher than that of an ordinary Dog; and the trait of sweating through the skin, particularly on the underpart of the body, rather than through the tongue, by panting after exertion, as other Dogs.”

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, the breed population in its native lands dwindled and was kept alive only by secluded Indian tribes in remote parts of Mexico and South America. The breed did not receive any official notice in Mexico until the 1950s. The FCM (Federación Canófila Mexicana), founded in 1940, was not prepared to declare the Xolo an official purebred at that time.

According to breed historian Norman Pelham Wright, author of The Enigma of the Xoloitzcuintli, Xolos first began to turn up at Mexican dog shows in the late 1940s. While it was recognized that these were indigenous specimens of a native breed, interest in them was minimal at that time. Reliable information was scarce and, with no national breed club, no Breed Standard existed by which to judge them.

Within a decade, however, the FCM realized the breed would be extinct if drastic action were not taken to save it. This led to the widely publicized “Xolo Expedition of 1954.” With the official sanction of FCM, Wright and the British Chihuahua expert Hilary Harmer, along with the Archduchess Felix of Austria, better known as the Countess Lascelle de Premio Real, and a team of other Mexican and British dog authorities set off to discover if any purebred Xolos still existed in remote areas of Mexico.

Eventually, Wright located and brought back sufficient numbers of good Xolos and it was these dogs that formed the foundation of Mexico’s program to revive the breed. A committee headed by Wright authored the first official Standard for the breed. The Xoloitzcuintli breed was first registered in Mexico in 1955. When on May 1, 1956, the “Standard” for the breed was adopted, the Xolo was finally recognized in its native land and is now the designated “Official Dog of Mexico.” With Mexico a member of the FCI, this gained the Xoloitzcuintle worldwide recognition, too.

In 1997, the Xolo was recorded in the AKC Foundation Stock Service for rare breeds. In January of 2011, the Xoloitzcuintli, an ancient canine molded by environment and function, joined his fellow primitive pariahs, the Basenji, the Canaan Dog, the Ibizan Hound, and the Pharoah Hound, among others, in the AKC Conformation show ring to compete with full recognition. In the US, all three sizes and both coats are now judged together as one breed in the Non-Sporting Group.

The Xoloitzcuintli is currently registered by the Canadian Kennel Club in the Non-Sporting Group for the Standard and Miniature, and in the Toy Group for the Toy Xolo.

In the FCI, the Xoloitzcuintli is judged in Group 5, Spitz and Primitive Types, recognizing their ancient origins.

The Xoloitzcuintli was actually first registered with the American Kennel Club (AKC) from 1887-1959 as the “Mexican Hairless” breed, but was dropped due to insufficient numbers of dogs being bred and registered. The photo with the “Mexican Hairless” chapter from the AKC 1935 Toy Dogs book should make it completely clear that this breed was IN NO WAY a true Xoloitzcuintli, simply a hairless Chihuahua.

On the following page are photos of Xoloitzcuintli that were present at the Xoloitzcuintli Club of America’s 24th Annual National Specialty, October 24, 2010, in Las Vegas, Nevada. This was the XCA’s last National before it became part of the AKC.