Home » Preservation Breeder? PRESERVE THIS!!!

Preservation Breeder? PRESERVE THIS!!!

Most every breed of dog owes its very existence to the need of humankind to fulfill a specific purpose. Were it not for this stark fact we might be very happy with a single kind of dog (let’s say, a Labradoodle). Fact is, though, we’re a demanding sort, and throughout canine history we have always sought after the perfect dog for a given task. On the one hand, we worship “versatility” while at the same time taking an oath to perpetuate purposefully bred dogs. We’ve all heard the argument that “AKC” will eventually wreck the breed while at the same time we see dogs bred solely for their working or hunting ability that don’t even vaguely resemble the breed from which they sprang. Is there a middle ground?

Fact is, though, we’re a demanding sort, and throughout canine history we have always sought after the perfect dog for a given task.

Most every breeder gives lip service to knowledge of the tasks for which a breed was developed. More often than not, that knowledge is limited to conventional wisdom and a few meager sentences published in an article like this. Knowing the exact job description and exactly how that job is performed will take you a long way toward breeding individuals that are anatomically able to excel at their work while at the same time possessing those breed characteristics that will enable them to do it well. The only trick here is that the breeder must know the job intimately and the dog must have a genetic predisposition to do it. Without both factors, form will certainly follow lack of function and the original breed type will eventually be eroded or lost.

Many years ago I bred and hunted a pack of foxhounds. Not just any hounds, mind you, but Old English Foxhounds. Many of the Masters of Foxhounds and Huntsmen of that day were quick to criticize these throwbacks to another era. “Too slow,” said some. “No voice,” said others. “Too big,” and several other observations that are not fit to print in a publication of this stature. But despite this wretched abuse at the hands of my colleagues, there was always a line of bitches to be bred. Why? Quite simply because this strain of hounds has retained its breed type and character through actual and continuous work at its designated purpose for 400 years or more. One knows well in advance what the stud dog or brood bitch is likely to produce. Call it stamped breed type if you wish. You know what you’re getting and you can use that rock solid line to breed into other lines to produce exactly (more or less) a dog or hound that fulfills your exact needs. That stamped breed type includes the whole package; outstanding conformation necessary to do the job well and the hard-wired predisposition to get it done.

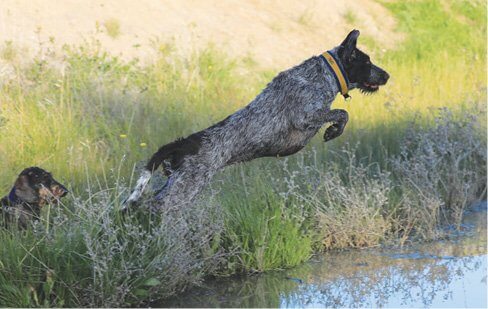

Despite the fact that most seminars and presentations begin with a statement that the breed “was originally bred for…” most ignore the fact that if you look hard enough you can still find outstanding examples of most breeds hard at work at their designated tasks even today. It is by spending some time with and observing the dog at work that one can understand the anatomical and temperamental attributes that it needs to get the job done in first class fashion.

Consider the English Foxhound as an example. The AKC standard says, “…straight stifles are preferred to those much bent as in a Greyhound.” Our training as conformation judges may lead us to seek out a dog or bitch with moderate rear angulation. Reasonable enough, but it is only through actually hunting with a pack of hounds that you can see the true effect of “moderate” angulation at the end of the day. Every hound moves well in the two or three counterclockwise trips around the ring, but it’s a different story at the end of a long, often cold, day of hunting that may cover fifteen miles. At the end of the day you call in your hounds and head home. There are often a few that don’t make it back and the hunt staff has to set out in a truck to pick them up. (These days it’s a bit easier to find them with GPS collars.) After a few weeks one notices that it is always the hounds with “moderate” rear angulation that require pick up. The ones that are straighter in the stifle have enough energy to go the distance and still come home at night. To be fair, there’s no way you are going to know this unless you’ve seen multiple dogs engaged in their vocation.

Or think of the Border Terrier. As versatile as the breed is today, at the outset it had but one purpose; extricating foxes from the rocky crags and crevice of the fells. Pay no attention to the art that you see with the little brown dogs trotting patiently behind hounds and horses. The standard was written to produce a terrier that could hunt with a reasonable amount of common sense and safety in a most inhospitable environment. The standard that was written for the breed contains the wording, “The body should be capable of being spanned by a man’s hands behind the shoulders.” Just a few words that seem somewhat irrelevant in the show ring, but to anyone who has hunted with a BT or even witnessed a real hunt, it’s really a matter of life and death. A dog that cannot be (easily) spanned is apt to get stuck underground and can block the passage of air in the tunnel, causing both the dog and its quarry to suffocate. Dig a ten feet deep hole at a feverish pace to rescue a brave terrier and you’ll soon be spanning every dog with which you come in contact and rejecting those that don’t fulfill the requirement.

Need more? How about the long, low Dachshund? It was and is used extensively as a hole dog on varying sizes of game. Like the standards for many, if not most, breeds, the Dachshund’s standard prescribes, “Rear pasterns – Short and strong, perpendicular to the second thigh bone.” Short hocksare the norm, but in the Dachshund they take on added importance. Unlike many terriers, the Dachshund hunts underground with a “lunge and retreat” movement. This type of work is particularly effective in getting the quarry to bolt or, if that doesn’t happen, keeping the Dachshund safe(er) while it holds the critter in place waiting for the diggers. Those short and strong rear pasterns are what enable the Dachshund to quickly shift into reverse, backing out of harm’s way. (You don’t spend nearly as much on vet bills for a Dachshund as you do a hard terrier.)

The list of these performance-related priorities is as long and varied as there are breeds. If you have a dog that was bred for a purpose there are always anatomical characteristics that are necessary in its job. For most of us, the importance of a few individual words or phrases contained in a lengthy standard are given a lower priority unless one has an in-depth knowledge of how the dog works and how that particular attribute comes into play in getting the job done. As a breeder (and as a judge) one needs to know that the individual dog can perform the tasks for which it is designed and, of equal import, has the innate desire to perform that work. This creates two hurdles for all of us to clear. First is to breed a dog that CAN do the job and at the same time WILL do the job. You need the hard-wired work ethic in addition to physical tools of the trade, and you need a means to prove that the dogs you breed carry that work ethic forward.

As “dog show people” or “AKC breeders” we take a great deal of criticism for what some see as ruination of a breed because of emphasis on appearance at the expense of function. They’re right. But it works both ways. Many of the folks who hunt or work their dogs breed exclusively for a single performance-related characteristic at the expense of the physical equipment needed to produce that performance. It would be great if we could meet in the middle, but that is only going to happen through mutual education. We need each other! This is true in some breeds more than others.

What we’re saying here is that unless we are breeding dogs that can and will do the exact job intended for the breed, we are falling short of producing the purposefully bred dog. The only way you’re going to know whether or not your stock measures up is to give all (or most) of your stock the chance to prove themselves at the work contemplated by the standard. It’s not as difficult as it sounds.

Some years ago, the late Dorothy O. Hutchinson (Rose Farm’s Dachshunds) grudgingly sold me a Miniature Wirehair Dachshund. Dee, like her mother before her, was the consummate breeder and a popular judge. Because she knew it would be used for hunting, which she abhorred, it took years for me to get the dog. Rose Farm’s Range Rover was a late bloomer and for the first four years of his life he just took up space. Of course, I kept Dee fully updated on Ranger’s lack of accomplishment. Still, at four years old, Ranger’s light went on and he became a very competent hole dog and hunter and, in fact, sired some dogs even greater than himself. At one point he passed the natural den test offered by the German parent club, the DTK. To my surprise, Dee adopted this win as her own, and all of her advertising from that point forward boasted the fact that the Rose Farm’s dogs could indeed fulfill their actual purpose. She knew it made them whole.

Real preservation breeding requires that the original work ethic of the breed be preserved one hundred percent and, to the extent possible, that unique temperament be tested and confirmed as often as possible. You seldom get the chance to evaluate it in the show ring and need to seek out other means of proving out the true working temperament in your stock. While you are most welcome to join me chasing rats through New York City, dispatching marauding fox on poultry farms, or tracking feral boar across Texas, you don’t have to get wet or dirty to gain firsthand knowledge of your breed’s primary function.

Where there’s a will, there’s a way, and in many breeds there are tests and simulations readily available to prove out your dogs’ instincts. In many parts of the world, a bench championship requires the successful completion of a working test if there is one available for that breed. It’s not real work, of course, and no test or simulation can replicate the real working conditions, but a working test or trial will at least confirm that a given dog has the innate desire and ability to perform its primary function. Moreover, the little title on the end assures those who buy or breed that your dogs carry forward the ability, both physical and mental, to fulfill their (original) purpose. Purposefully bred, right? Preserve this!

Preservation Breeder? PRESERVE THIS!!!

By Richard Reynolds