Home » The Dachshund’s Vocation: Why It Matters in the Conformation Ring

The shortest interview for additional breeds in AKC history occurred about forty-some years ago when the Field Rep (they weren’t “Executives” yet) looked me square in the eye and asked me, “What is the country of origin and the original purpose of the Scottish Deerhound?” I was younger and somewhat headstrong, and in retrospect, my immediate exit may have been unwise. I would ask your indulgence, then, reading through this rather lengthy article, when indeed the title might seem obvious. The Dachshund breed is difficult to judge, in any case, and downright impossible if you don’t have priorities based on the anatomical tools the breed needs to do its job.

We all know that “Dachshund” in German means “Badger Dog,” and we all have a general concept of what a badger looks like. Just to confuse things, you’ve also heard of the German “Teckel” which everyone knows is essentially the same thing as a Dachshund. Or is it? Few of us have ever worked a Dachshund on a badger, or for that matter, dug to a Dachshund at all. The process isn’t at all what it seems and several articles recently published by Conformation “authorities” in the Breed ring have it a bit wrong. Let’s take a look at the original job description for the Dachshund and how the Breed Standard relates to getting the job done.

While many breeds were purposely designed to share physical attributes with their quarry (think of the size, spanning, and pelting in the Border Terrier), this is untrue of the Dachshund. The European badger (Meles meles) can weigh in excess of 37 pounds. That cute little white-striped face contains a set of 18 teeth arranged in a fashion similar to canids. The claws too are a tool of defense, with five on each foot used both for digging and fighting. Badgers (once known as brocks) tend to live in underground mazes of tunnels (known as setts) which may comprise several hundred feet in length and depths up to twenty feet or more. When their numbers were plentiful in Europe, particularly in the UK, those tunnels formed a considerable detriment to agriculture, and as the population increased, so too did the damage a clan of them could do to even the hardiest crops. Badgers, like foxes, are omnivores and will eat almost anything. For the good they may do in ridding an area of smaller vermin, the damage inflicted to crops of fruit, wheat, corn, even birds’ eggs can be devasting. Add to that an often-unpleasant disposition (reported to be worse than some dog show judges) and you have the raison d’être for the Dachshund breed.

In recent years, we’ve found there’s not much that a Dachshund can’t do. They are extremely versatile, and one of my favorite dogs has 45 (yep, I counted them) various titles after his name. Everything from Obedience to Fast CAT to Scent Work and Agility, all things far removed from badger hunting. What really counts, though, is the “Dual Champion” in front of his name. That’s earned by scent trailing rabbits which, of course, is a form of hunting. Standard Dachshunds excel at blood trailing and have enabled the recovery of thousands of wounded game. None of this, however, is what the breed was designed for; they just serve to make a good dog better. The Breed Standard was written for dogs that go to ground, and the ability to perform that function should be uppermost in the Conformation judge’s mind. (Experience has shown that a dog that is game enough for Field Trials or Earthdog will most generally be temperamentally suited for hole work.)

The Breed Standards, both AKC and FCI, are written to describe a dog that can perform its primary function most efficiently and with at least a modest degree of safety for the dog itself. Going to ground for badger is not a means to a longer lifespan. The dangers are multiple and the conformation of the Dachshund is intended to increase its ability to work effectively and minimize the likelihood of injury or death, which even today is all too common. The modern-day versatility of the breed in all its variations has little relevance to the Standards. The Dachshund is, first, last, and always, a hole dog and should be built and judged as such.

A “hole dog,” in the vernacular of those of us who play in the dirt, is one that will “mark” a hole (or burrow, sett, warren, den, or whatever), indicating that its owner is currently at home, and then enter the earth and work its way right up to the quarry. Initially, the primary purpose is to let the hunter know exactly where, underground, the quarry is located and then to either hold the quarry in one place until it can be dug, or in the alternative, cause the quarry to bolt from another entrance. In the real world, the quarry is most often backed up into a dead-end tunnel and held in position while the dog “works” the quarry by growling, barking, biting, etc. It is not the Dachshund’s primary mission to kill the quarry or to drag it from the den. One of the amazing attributes of the Dachshund breed is its ability to get the job done without getting injured itself. It happens, but not all that often.

Dachshunds may be underground for extended periods of time. In my own case, that was an uninterrupted 72 hours. A dog that barks loudly when it has located quarry is much preferred to a less vocal worker. It is for this reason that even the smallest of Dachshunds usually has a bark that sounds very much like a bigger dog. In days of yore, hunters had to be able to hear the dog to find it. They stuck their head in the hole, inserted a hose as a listening tube, or even listened for vibrations using an iron digging bar inserted at various places along the tunnel. These days we attach a tiny locator collar with a ULF radio transmitter to the Dachshund’s collar in order to determine with pinpoint accuracy where the dog is working.

Using the radio receiver, we can also tell if the dog and quarry are moving, or if the dog has accomplished its goal of backing up the quarry. Once the hole dog and quarry are stationary, digging begins in earnest. If we’ve gotten it right, the hole is sunk so that it opens between the Dachshund and its quarry. The Dachshund is then generally removed through this “stovepipe” and a terrier put down to do the heavy lifting.

Once the stovepipe has been sunk and the dog removed, the quarry is humanely dispatched, frequently with the use of badger tongs, or more recently, a catch pole. If we don’t have orders from the landowner to dispatch vermin, it may be relocated to a more suitable location.

It is not the Dachshund’s role to seriously engage the quarry, although that sometimes happens. Rather, it holds the quarry at bay or forces it to bolt out the back door to the waiting lurcher, purse net, or hunter. A Dachshund almost never dispatches its quarry. Perhaps for this reason the breed is relentless and effective. In the US, the Miniature Dachshund (at 11 lbs or less) can move through the smaller spring tunnels of woodchucks, while at the same time having the will and stamina to work raccoon and fox in larger holes. Standard Dachshunds can work the permanent dens of fox, raccoon, and badger, and can occasionally work groundhog dens later in the fall when those holes have been enlarged to accommodate the extra weight of hibernation.

The Dachshund’s particular style of hunting makes it a highly desirable hole dog. That style is derived in part from training and experience, but even more from its genetics. It is not the “in your face” style of the terrier, but rather a controlled (but relentless) charge and parry motion that is ideal for holding or bolting. In many cases the dog will work for an hour or more, underground. This back and forth working style is the bane of AKC Earthdog judges. Those rules require that the dog work for the most part within 12 inches of the quarry. The coming and going of many Dachshunds leads to their failure to qualify in the tests but is an expected part of their innate hunting style.

You’ve probably noticed, too, that Dachshunds come in sizes (as well as coats). Those sizes are directly related to the size of the quarry which they are asked to hunt. In FCI, there are three sizes: the Standard, the Zwerg, and the Kaninchen. While in the US we still divide the sizes by weight, the FCI, quite recently and at the request of the German parent club, revised their Standard to use measurement of the girth at the chest as the determining factor. In working reality, this has much more relevance than weight. It really does determine which size Dachshund you want to use against a specific quarry:

Standard Dachshund:

Males: over 37 cm (14.56 in) – up to 47 cm. (18.5 in)

Females: over 35 cm (13.75 in) – up to 45 cm. (17.71 in)

Miniature Dachshund:

Males: over 32 cm (12.6 in) – up to 37 cm (14.56 in)

Females: over 30cm (11.8 in) – up to 35 cm (13.75 in)

Rabbit Dachshund:

Males: 27 cm (10.6 in) – up to 32 cm (12.6 in)

Females: 25 cm (9.8 in) – up to 30 cm (11.8 in)

Adhering to these measurements virtually eliminates the exaggerated keel that we see so often in the US and helps to ensure the thorax “appears oval and extends downward to the mid-point of the forearm.” A larger, exaggerated thorax is a detriment to the dog’s ability to work even a larger tunnel. A leading cause of death in earth-working Dachshunds (and terriers too) is suffocation resulting from their own body blocking the air supply while they are facing the quarry. A dog of the proper size, with a proper keel and a forechest that is not exaggerated, and of sufficient leg length is more apt to be able to move backwards and forwards in the earth (as is the Dachshund’s style of hunting) and maintain an air flow. Maintaining the Standard (and not overdoing it) really is a matter of life and death.

The Dachshund is an achondroplastic breed, which is a fancy term for short-legged dwarfism. It requires the proper “wraparound front” described in the Standard. There is no other way the dog can function. None at all! It provides the freedom of movement necessary for the dog to both move and dig underground with the highest degree of safety possible. The slightest suggestion of a straight front detracts from both ability and safety. (A draft law published in Germany, February 2024, would prohibit breeding dogs with “skeletal anomalies.” This is actually contrary to the health and safety of the Dachshund and evidence of the misunderstanding of the breed.)

No dog digs by pushing dirt to the side. Think about it. It’s a narrow tunnel to begin with and there is no room at all at the side. The dog digs, pushing dirt and debris under it with the front legs while pushing that same dirt behind it with the rear. It can then move forward, propelling itself into the space it has created. It does not rest on an exaggerated keel whilst flapping its arms like a seal in the ocean. To accomplish this, it uses its paws and both front and rear legs, along with its teeth, to remove roots or other obstacles.

The most common problem encountered in hunting Dachshunds to ground is their getting stuck underground in a tunnel. A dog that is too heavy or too large is more apt to get stuck than one with a reasonable girth and leg length. If the dog is stuck and mute, you’re going to dig a lot of holes to rescue them. When mass of the dog blocks the tunnel in its entirety, the air supply is limited and both dog and quarry may suffocate from lack of oxygen. That’s a heck of a motivation for fast digging. In my own case, I had two dogs stuck for three days in the rotten root of a hickory tree about eight feet underground while we worked feverishly to locate them. Being Miniatures, they had enough space around them to get air.

The FCI (and Deutcher Teckelklub 1888 e.V.) Standard also mandates “a ground clearance of about one third of the height at the withers.” That’s a useful proportion. The AKC version specifies the thorax and keel “extends downward to the mid-point of the forearm.” Either way we’re looking for adequate ground clearance that isn’t found in many of the Conformation dogs today. Quite often one hears that a “Teckel” can be identified by longer legs. The legs aren’t any longer, the thorax is less exaggerated.

In addition to its forequarters, the Dachshund at work makes very good use of its teeth. The AKC Standard requires only a scissors bite, or alternatively, a level bite, although it does stipulate “powerful canines.” The FCI Standard goes a step further and makes poorly placed canines a disqualification: “Disqualifying Fault: Faulty positioning of the lower canines.” And it requires, “canines exactly fitting into each other.” (FCI Breed Standard No. 148)

Lower canines that do not easily clear the upper palate are basically useless for work and present a serious health hazard to the dog itself. I’ve learned this the hard way, and unfortunately, we are seeing more and more of this in the Breed ring. A dog can easily meet the AKC Standard while being subject to disqualification under the FCI version. From a purely functional standpoint, one cannot tolerate misplaced lower canines.

Watching a Dachshund work, even from above, which is our usual vantage point, it’s obvious that the rear legs are as useful and of equal importance to the front assembly. The AKC Standard defines the pasterns as “Rear pasterns – Short and strong, perpendicular to the second thigh bone.” The length of the rear pastern is of paramount importance to the Dachshund at work. It must have a full range of motion (not sickle-hocked) in order to move the dirt. Even more important, the short rear pastern is what enables the Dachshund to shift into reverse, backing up rapidly to avoid the lunging and attack of its quarry. Regardless of the size of the dog, a comparatively short rear pastern is an important (maybe the MOST important) anatomical asset in enabling the “lunge and parry” style of work that is deeply instilled in the breed. Simply put, a longer rear pastern can be a severe handicap to the Dachshund in its work.

In days of yore, the AKC Breed Standards contained a Scale of Points that attempted to set priorities in judging the various breeds. Thankfully, most of these have been removed, since a judge’s priorities in the Breed ring on a given day are very much dependent on the entry they have to work with.

So, now that we’ve talked about the job description of the Dachshund (it’s not historical, it’s right now, present-day real), let’s look at some options for conformation priorities:

There’s work for big dogs and little dogs, so size is only critical in determining how big a hole you are going to put the dog in. At a year, under our current system, a Miniature should weigh 11 pounds or less. Hopefully that will give you a girth of about 14.5 inches or less. Do not be afraid to call for the scales. Use them. It could be a matter of life or death.

A proper achondroplastic “wraparound” front is absolutely necessary. With anything else the dog can’t dig.

An exaggerated keel and/or thorax is both a danger and a hinderance. The Standard specifies, “extends downward to the mid-point of the forearm.” Anything that exceeds that proportion, even a little bit, is a danger to itself.

I have not, for obvious reasons, discussed the backline of the Dachshund. Suffice it to say that anything other than a ramrod straight back line, perhaps with a slight rise over the loin, should be seriously faulted. Most would hesitate to work a dog with either a saggy topline or an inappropriate rise.

Although their positioning is not directly mentioned in the AKC Standard, the lower canine teeth must fit properly with the uppers and must clear the upper palate itself. Misplacement is a disqualification under FCI rules and should be seriously faulted here. The canine teeth are the tools that count!

Although they comprise only one short sentence in the Standard, the (short) rear pasterns are vitally important to the Dachshund’s ability to dig, move, and escape danger. To the working dog, they are equally, if not more, important as the forelegs. There are various tricks of the trade for gauging the length of the rear pasterns, but the easiest is to compare the height of the rear pastern to the elbow. It’s an approximation, but you get the idea.

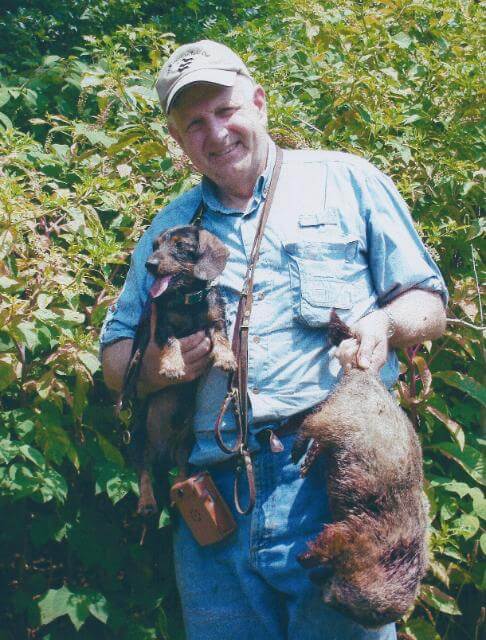

The Dachshund’s work ethic is to “work” the quarry using a lunge and retreat method to cause the quarry to remain in one place within the den, or in the alternative, to bolt from a rear entrance. In the photo above, Huey, a homebred from Rose Farm lines, worked this large woodchuck in the earth for almost two hours before causing it to bolt to the waiting lurcher. (You can see the radio transmitter on his collar and the brown receiver on my belt.)

Anke Masters photo

The Dachshund was and is bred to hunt its quarry deep in the earth. The “Badger Dog” today is still engaged in the active hunting of not only badger but a variety of quarry from rats and rabbits to fox, raccoon, and even wild boar. It’s conformation, though, directly addresses its use as an earthdog.

The Dachshund’s prime quarry is the badger. The animal is a formidable opponent, with teeth and claws that are both tools and weapons of defense. Badgers can weigh up to 40 lbs, although most are smaller. A badger sett is both long and deep, and can cause considerable damage to agriculture. The photos above are the American badger (Taxidea taxus). A Dachshund that adheres closely to the Breed Standard in both conformation and temperament is well equipped to deal with badgers, whether European or American. Badgers are a protected species in the UK and Canada, but are hunted in the US and Europe. photo credit Mikael Males and Holly Kuchera

“Short and strong” rear pasterns (in all varieties) as demanded by the AKC Standard are of prime importance. They enable the dog to move dirt under itself while at the same time enabling it to “shift into reverse” and escape attack by the quarry. The lunge and retreat working style of the Dachshund is vital to its effectiveness and safety. Julia Szer photo

Lower canine teeth that do not fit closely into the upper canines and that do not clear the upper palate are a disqualification under the FCI Standard for the Dachshund. This placement leads to a poor grip in hunting, but more importantly, is almost sure to cause problems with infection of the upper palate, the tooth, and the lower jaw. The condition is often corrected by removal of the misplaced teeth. Usually the misplaced canines are also the sign of a weak underjaw. The top photo shows proper placement of the canines.