Home » Stretching the Truth

Recently, I watched a YouTube video of Usain Bolt, the fastest man in the world, performing a warm-up routine. A trainer took each of his legs and put the hip and knee joints into flexion for about one second. Then Usain Bolt did some dynamic stretching, including normal running and running with high knees for short distances, and some sudden accelerations from a stopped position. A little walking around, and he was ready to go! In the comments section were many submissions like “I thought we weren’t supposed to stretch!” and “But he’s only stretching for a few seconds!” and so on.

Whether or not to stretch, and if so, how and for how long, is a huge controversy in human sports medicine. Since there are no published articles on the effects of either static or dynamic stretching in the dog, we rely on the literature about stretching in humans and apply those findings to dogs. As a result, the same controversy exists in the dog world.

There are numerous articles that say that stretching helps to improve human athletic performance. And there are just as many that say it doesn’t and might even reduce performance. There are numerous articles that say that stretching helps to prevent injuries. And there are just as many that say it doesn’t. You can see why the subject is so contentious.

As for dogs, they often stretch themselves, usually with a nice, long play-bow when they awaken, so it must be helpful, right? I wish it were that easy…

Luckily, there are two published meta-analyses that have addressed the effects of stretching in human athletes. A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis that combines the results of multiple scientific studies that address the same question to use pooled data to establish a consensus. It is considered the highest form of scientific evidence. The two meta-analyses come to the same conclusions, so only the more recent one is discussed here.

The meta-analysis by Behm et al, 2016 examined 125 published studies to determine whether and how static and dynamic stretching affected performance and injury prevention in sports activities that took place shortly thereafter.

They described two main types of stretches:

Only 12 of the 125 studies examined this question, and those covered a wide variety of types and duration of stretches, as well as various performance activities. Overall, these studies suggested a 54% risk reduction in acute muscle injuries associated with static stretching, but it is possible that was because of the reduction in performance. The study could not evaluate whether static stretching reduced the risk of chronic, overuse injuries, which are the ones we encounter most often in our active dogs.

No studies examined this question.

Summarizing the findings, it seems that, in humans, static stretching reduces performance but also reduces the risk of acute muscle injuries, and dynamic stretching creates a tiny increase in performance.

Do these data apply to our active dogs? Well, that one is easy! Let’s look back at the definition of static stretching: it involves “lengthening a muscle until either a stretch sensation or the point of discomfort is felt.” Since we are completely unable to discern when our dogs are feeling a “stretch sensation,” and given the fact that most dogs hide pain until it is severe, we also cannot determine when our dogs reach “the point of discomfort.”

For those reasons, static stretching is inappropriate for dogs. If you wish, you can do dynamic stretching, in which your dog initiates the action itself, but it is unlikely to improve your dog’s performance significantly.

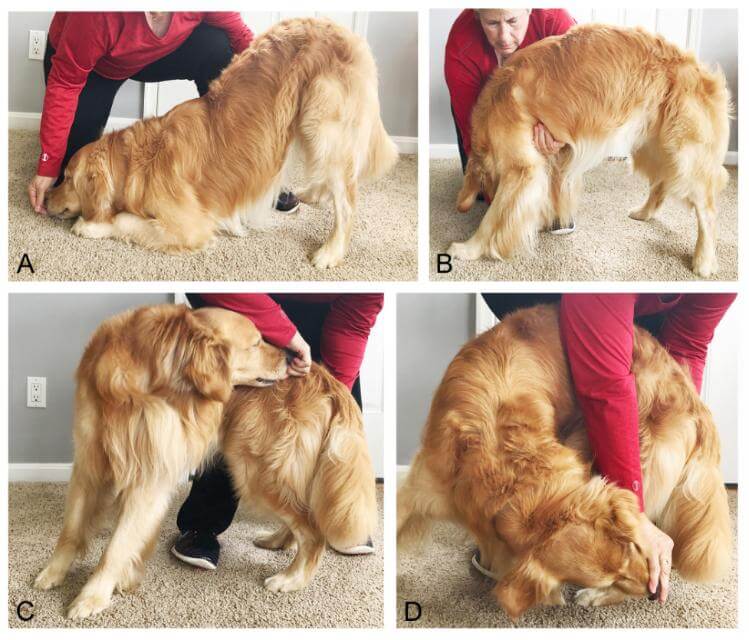

The play bow is a good example of dynamic stretching for the front limbs and the spine. You can train your dog to initiate a play bow on its own by rewarding when those natural stretches occur, or you can lure your dog into a play bow as shown in Figure 2.

Dynamic stretches are best done after the dog is slightly warmed up, so a good warm-up for your dog might consist of: