Home » A Closer Look At The Canine Front

As in all things “dog,” the correct shoulder assembly varies from breed to breed. This variation depends upon the tasks the different breeds were developed to perform.

In a quick review, every dog has the same number and kinds of bones. What varies are the length of the bones and the angles at which they join, which differ from breed to breed—and also from dog to dog within each breed. Bones are the building blocks of structure. Bones are classified according to shape and function. One of the functions of the skeletal structure of the dog is to supply a sufficient area for the attachment of muscles. This is especially important with the shoulder assembly!

Smooth muscles account for approximately one-third to one-half the total body weight. Ligaments hold bones together while tendons attach muscle to bone. Tendons are considered to be a part of the muscle structure, ligaments are not.

Since 60-75% of the weight of the dog is concentrated on the front (due to the head and neck), the front assembly of the dog is of vital importance to the function of the dog as a whole. Most of this weight is flexibly carried by the forelimbs, using muscles and tendons ONLY.

The shoulder assembly is a complex interaction of bone, muscle and connective tissue, which includes the tendons and ligaments. I do not want to get into the controversy of the degree of angulation required in many standards; angles vary from breed to breed. As many have demonstrated with radiography, the true angulation of many (if not most) breeds isn’t the 45-degree layback or the 90-degree angle formed with the juncture of the shoulder blade to the upper arm—but this is what we have to work with—and I cannot change the terminology.

What I believe we need to do is leave the measuring devices at home so that we can train our eye to see the balance in the standing dog, and [learn] how to apply that to movement. What we should all have in common (no matter the breed) is the goal to produce a dog that can acquit its duties with the least amount of energy.

The German Shorthaired Pointer Standard states: “Forequarters: The shoulders are sloping, movable, and well covered with muscle. The shoulder blades lie flat and are well laid back nearing a 45 degree angle. The upper arm (the bones between the shoulder and elbow joint) is as long as possible, standing away somewhat from the trunk so that the straight and closely muscled legs, when viewed from the front, appear to be parallel.”

The fore assembly of the dog is far more than just the shoulder blade (scapula), but it is this oddly shaped bone that serves as the foundation of the fore assembly. The bones of the skeleton form the armature—around and upon which the form of the dog develops. In my 50 years as a breeder (and also in my tenure as a conformation judge), I have come to the conclusion that the correct shoulder assembly for any dog breed is the hardest to come by and the easiest to lose.

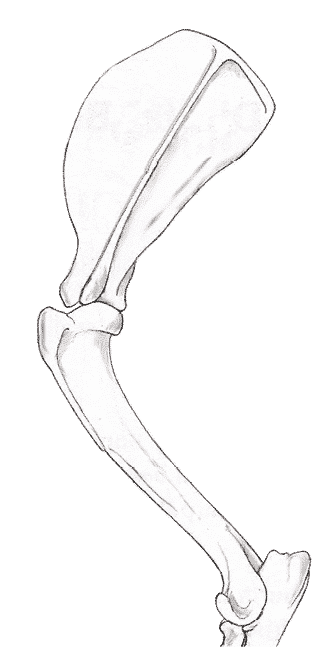

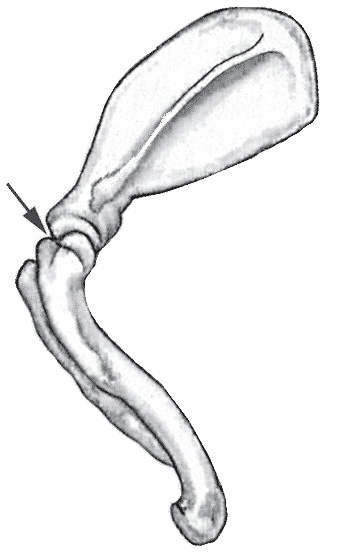

The shoulder blade articulates with the upper arm via a shallow ball and socket joint. This angulation provides lever action in which the muscles exert force, allowing them to change their position thus producing movement of the leg, which in turn propels the dog forward. (See Figure 3.)

The physical landmarks of the angulation of the shoulder to the upper arm that can be palpated on physical examination are:

The space between B and C where the shoulder blade articulates with the upper arm is an easily felt notch on physical examination.

The shoulder blade (scapula) is the major point of attachment of the forequarters to the body (thorax) of the dog. The form of the shoulder blade never ceases to amaze me. The bone is flat on the back (dorsal) side (see Figure 4, B) and is fastened to the trunk via an attachment made of muscles, rather than a bony joint. This allows for the scapula to rotate with the movement of the upper arm (humerus) so that it can move smoothly across the rib cage.

The raised bony “spine” (see Figures 4 and 5, A) protrudes upward from the front surface of the bone allowing for even more muscle attachment. This spine of the shoulder blade is one of the major “landmarks” for physical examination. The ligaments joining the bones are labeled “D” in Figure 4 and “B” in Figure 5.

The shoulder blade is attached to the neck (cervical vertebrae) and ribs (thorax) by muscles beneath the blade (dorsally) on the flat side of the shoulder blade—and above from the spine of the shoulder blade (see figure 6). Muscle “A” rotates the shoulder blade, “B” extends the forearm and “C” straightens the elbow.

This muscular attachment of the fore assembly to the body not only attaches the two areas one to the other, it also supports the weight of the trunk and its muscle groups, and serves to advance and retract the leg as well as move the neck. You need not learn all of the names and functions of each of the muscles in the canine body, but you do need to have an understanding that it is muscles that move the bones. The upper, larger edge of the shoulder blade is placed slightly below the spines of the spinal (vertebral) column (see Figure 7).

The shoulder blade has no joint connection with the upper chest and spine, but lies between and is fused to flat muscle attached at the 3rd–9th vertebrae. Ideally, the highest part of the shoulder blade lies just below the level of the first through fourth vertebrae with the spine of the shoulder blade (scapula) pointing to the highest part of the blade.

In the majority of breeds, the upper arm is the largest bone in the fore assembly and, even though most breed standards call for an upper arm length as long as the shoulder blade, it is, for most breeds, actually longer than the shoulder blade. This is because the “point of the shoulder” usually referred to in measuring body length is actually the upper end of the upper arm (humerus) (see Figure 8).

The articulation of the shoulder blade with the upper arm forms the shoulder joint. This “spheroid” (ball and socket) joint allows for a very wide range of motion so that the dog can change directions quickly and easily. It is at this shoulder joint that the leverage is applied by the force of the muscles to change the position of the bones, allowing movement of the leg. The properly articulated bones of the shoulder and upper arm also serve to increase the area for the muscles to attach the entire front assembly to the trunk of the dog; and the more fit the muscles, the stronger and more flexible the dog is, which allows for more supple movement (see Figure 6).

This article will be continued in the next issue.

As always, if you have any comments or questions or would like to schedule a seminar, contact me via email—jimanie@welshcorgi.com.

A Closer Look At The Canine Front – From the October 2020 Issue of Showsight Magazine.

By Stephanie Hedgepath