Home » Closer Look at the Humerus (Upper Arm) of a Dog

Form Follows Function – Closer Look at the Humerus (Upper Arm) of a Dog

The forequarter of the dog is responsible for both the steering and braking ability of the animal. It lifts the center of gravity as the dog moves forward, acting somewhat similarly to the pole of the athlete participating in the pole vault. It is also a stabilizing force that opposes lateral displacement and enables the dog to turn on a dime. While the rear propels the dog forward, the forequarter also adds propulsion forward through the gripping action of the front foot on the ground, which pulls the dog forward somewhat while at the same time serving to stabilize the forequarters to allow the driving force of the hindquarters to propel the dog forward over the front assembly (pole vault). The scapula is attached to the thorax by fibrous connective tissue; no fixed joint attaches the forequarters to the thorax (body) of the dog.

While the rear propels the dog forward, the forequarter also adds propulsion forward through the gripping action of the front foot on the ground, which pulls the dog forward somewhat while at the same time serving to stabilize the forequarters to allow the driving force of the hindquarters to propel the dog forward over the front assembly…

In any discussion concerning the dog’s forequarters, much of the emphasis is placed on the scapula (shoulder blade). The positioning on the chest and the degree of layback and proper layon of the scapula does much to determine the forward reach of the canine front leg.

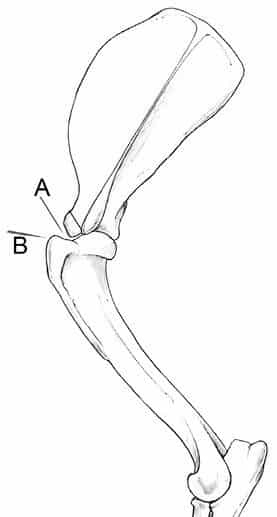

The humerus (upper arm) is often commented upon concerning its articulation with the scapula to form the shoulder joint. This shallow ball and socket joint can move in any direction, which is why the forelegs may move laterally (winging, paddling, etc.), mainly to waste time when the rear drive exceeds the front reach of the dog. The shoulder joint primarily functions in inflection (bending or drawing the parts together) and extension (the straightening of the limbs). This junction forms the point of the shoulder. (See Figure 2A.) The landmark felt when determining the point of the shoulder (Figure 2B) is the upper point of the humerus.

The primary function of the humerus is to support the body and provide some force in propelling the dog forward, and it also serves to provide balance to the dog. In most breeds, the humerus is approximately equal in length to the scapula; the major exceptions are found in the achondroplastic (dwarf) breeds.

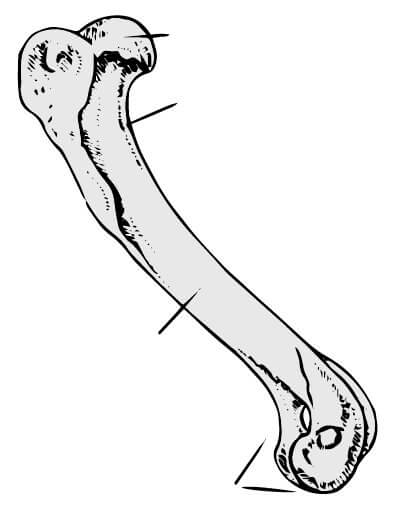

Many breed standards call for a 90-degree angle of the humerus’ body with the scapula’s spine when the dog is in a normal standing position. Given the landmarks that are most readily discernable by someone without access to an x-ray machine, this is a reasonably accurate way to determine angulation, depending upon which “landmarks” one is using. You can find a great explanation of how to estimate the forequarter angle on pages 98 & 99 of Claudia Orlandi’s book, Practical Canine Anatomy & Movement, which I highly recommend to those who want more in-depth knowledge on the subject. The humerus divides into three sections: the head, neck, and body. (See Figure 3.)

The body or shaft of the humerus is a long, slightly S-shaped bone that enlarges as it nears the junction of the elbow joint. The humerus bone ends as a condyle joint at the elbow. A condyle is shaped somewhat like a pulley, with a deep notch in the center into which the ridge of the upper portion in the ulna bone of the forearm fits to form the most stable portion of the elbow joint.

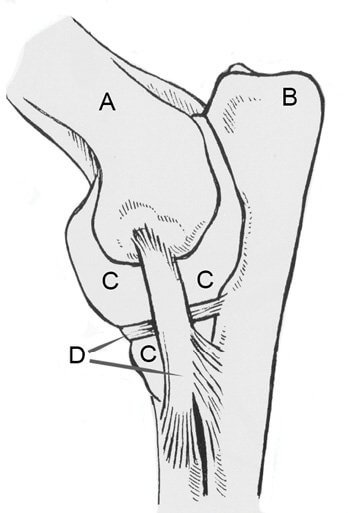

The elbow is a hinge joint. Therefore, when the forelimb is vertical, the joint is in complete surface contact and can be considered “locked” in place. When the limb is partially extended and when it is retracted, a loosening of the joint occurs. When the elbow is completely extended, the point of the elbow (olecranon) fits into a matching channel of the humerus, providing rigidity for the column of bones. Interestingly, this hinge type of action generally allows the lower limb to swing only in the direction it is pointed. (See Figure 4.)

Determining the length of the humerus (upper arm) is vital when seeking the angulation of the scapula to the humerus. If the layback of the scapula is correct and the humerus is either too long or too short, the reach and the amount of leg lift (as well as the head carriage of the dog) can be affected. A dog with a short upper arm can lack forechest because the front assembly is placed too far forward, thus shortening the dog’s forward reach. There is a definite lack of support under the deepest part of the chest when the upper arm is short, and therefore, there is little “return” of the upper arm to position the elbow and the foreleg under the heaviest part of the chest. Legs placed too far forward put more stress on the muscles and bones of the forequarter. A short upper arm also hampers the ability of the leg to incline under the body toward the centerline of the dog when the dog is in motion.

A shortened upper arm can result in a dog that moves wide when coming toward you and rolls from side to side when seen from the side at a trot. This rolling or lateral movement (lateral displacement) in a moving dog wastes energy and wears the dog out. It may well eventually lead to a breakdown in the dog to the point it can no longer fulfill the job for which it was developed. Less often seen is a humerus that is too long, but this too causes changes in the prosternum and affects both the placement of the neck and the head carriage. “Too much” is as bad as “too little.” Anatomy is a fascinating science, and it always amazes me how every part of the dog must be in balance with the whole animal for everything to work flawlessly. We all know, however, that there is no perfection in nature and that every Best in Show dog has at least one fault. Our duty as breeders is to always strive for the “ideal” set forward by our breed standards. By doing this, we are doing all that we can to preserve our beloved breeds for future generations to love and be loved by these marvelous creatures we call dogs.

Please address any questions or comments to me via email: jimanie@welshcorgi.com.

Form Follows Function – Closer Look at the Humerus (Upper Arm) of a Dog

By Stephanie Seabrook Hedgepath