Home » Form Follows Function: Toes Up!

In a previous article on the foot of the dog, I wrote about the adage: “No hoof, no horse,” common in the 18th century in North America, which speaks to how important the feet are to an animal. A lame horse is useless to its owner. The same can be applied to the dog: “No foot, no dog.” I first heard the phrase used to describe a dog when judging an ARBA show in the late 1990s. A fellow judge, whom I greatly admired, chastised me for placing a hound in the Group with faulty feet. His comments led to a great discussion and the beginning of a good friendship. The feet are the foundation on which the dog is “built.” Just as the foundation of a building must be solid, so must the feet of the dog be correct for its breed.

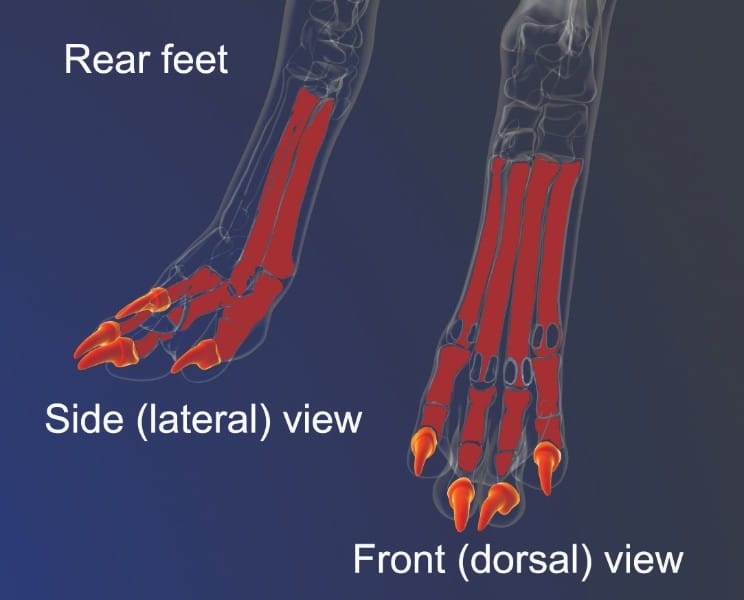

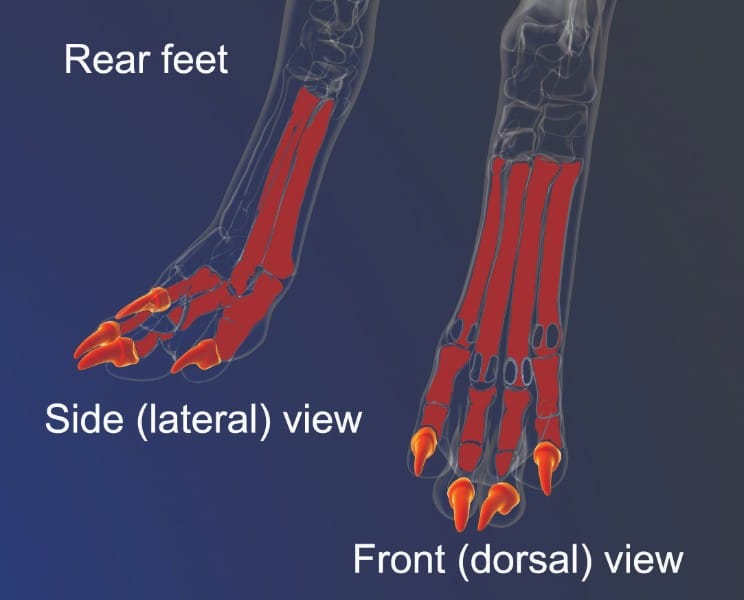

Dogs are digitigrade animals; this means that the weight-bearing surface of their limbs is their digit (toe). The canine phalanges are, thus, very important. They are virtually identical in their structure in the hindlimb and forelimb. The main differences are that in the forelimb we have metacarpals and the metacarpophalangeal joint, and the hindlimb equivalents are the metatarsals and the metatarsophalangeal joint.

The feet serve as a base of support for the dog, as a cushion to absorb shock, provide traction to start movement, and as a brake to stop. Each of the toes (digits/phalanx bones) is supported by a pad composed of thick layers of fat and connective tissue covered with several layers of skin forming a thick, horny skin. This thick skin makes it possible for the dog to comfortably work over many types of terrain, from abrasive to slick and slippery, which also varies greatly in temperature. The pads serve as a weight-bearing, shock-absorbing cushion and aid in traction.

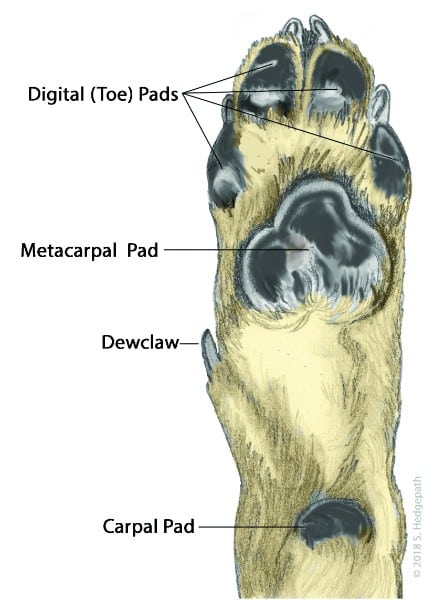

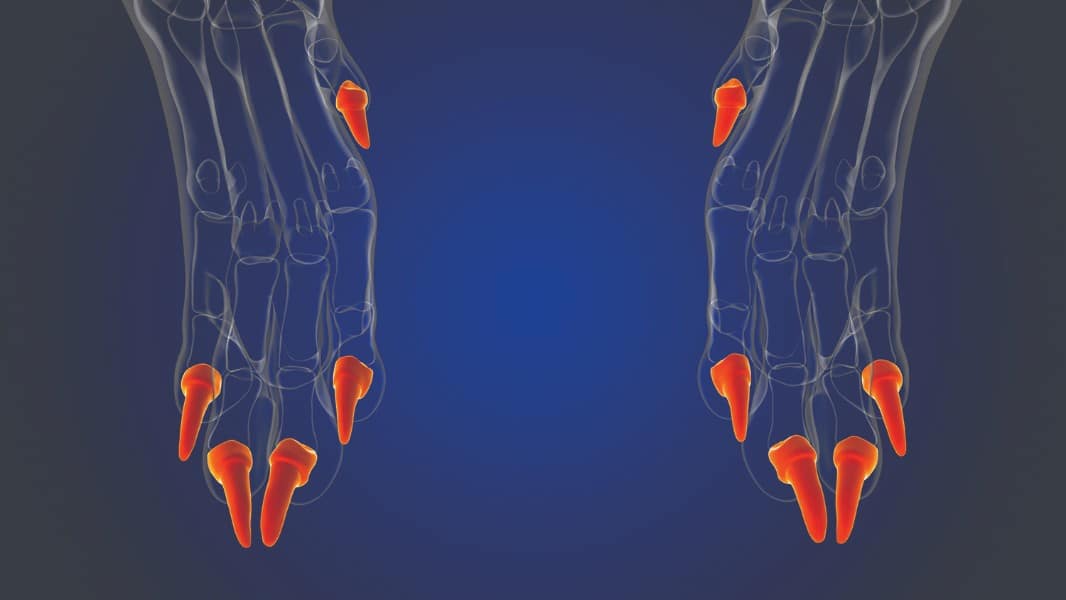

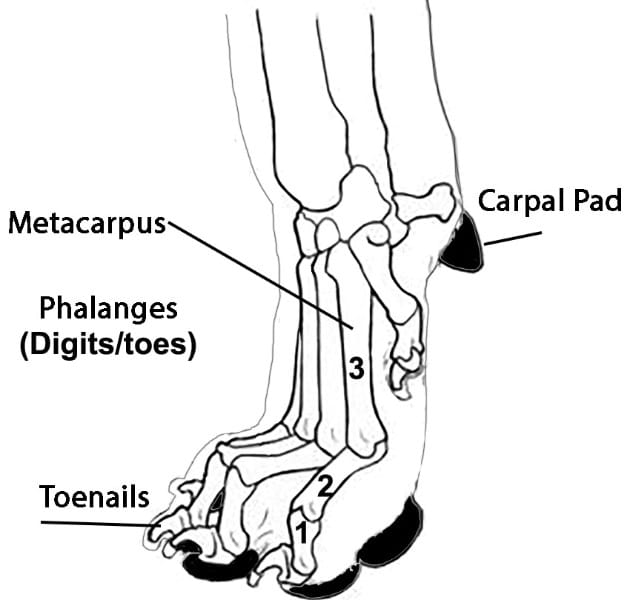

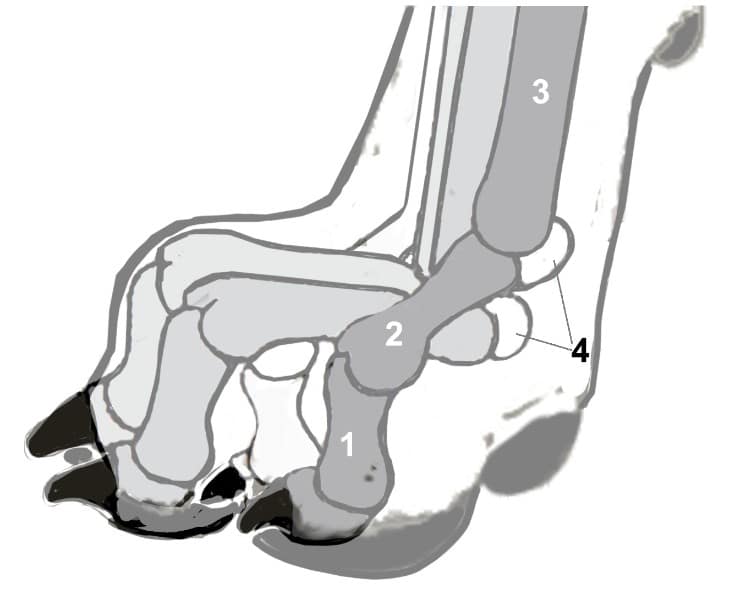

The anatomy of the canine foot is composed of the toes, which have three bones, and the pasterns plus their pads, the dewclaw (no pads), and the carpal pad (Figure 1). The foot (both front and rear) has four functional toes, each containing three bones. These three bones are the toenails or distal phalanx (Figure 2), the middle phalanx (toe) bone (Figure 3), and the proximal phalanx (toe) bone (Figure 4). Each toe has a pad. The dewclaw, if not removed, differs from the other four in that it only contains two bones. The pastern contains the four metacarpal bones (Figure 5).

[wonderplugin_3dcarousel id=69]

The toenails are composed of keratin, enabling the dog to grip the ground and scratch (both the ground and themselves) and help maintain a grip on something they are chewing. The average dog has four functional toes (digits) and may be born with a fifth toe called the dewclaw, located on the inner side of the pastern on the front leg, and is considered to have lost most or all of its original function. Dewclaws may also be found on the rear legs. Several breeds require dewclaws on some or all of the legs, but on the average dog, they are usually removed, especially if they have no contact with the ground.

Next comes the metacarpal bones in the foot, commonly called the pastern (Figure 6). These bones, similar to the human palm, join the pastern joint (carpus joint) with the toes (digits) of the dog. Four metacarpal bones (five, if the dewclaw is not removed) lead to one of the toes. Of the four, the outer bones (leading to the two outside toes) are shorter than the inner ones (leading to the two center toes). These metacarpal bones relate to the palm of the human hand—between the wrist and the fingers. The breeder must understand that the dog walks only on the toes/digits of his foot (Figure 6).

The carpal pads are found on the front feet further up the foot near the wrist or pastern joint. They are of the same structure as the pads under the toes. The carpal pad (Figure 1) comes into play on steep or slippery surfaces by helping the dog to retain its balance, and is also sometimes referred to as the “stopper pad,” working as a brake. This pad also supports the crouching/crawling dog (think Border Collie approaching livestock) as it moves over rough terrain.

The metacarpal pads on the front feet (metatarsal on the rear) are the largest pads on the dog’s foot and are located behind the pads of the toes. As with the toe pads, the metacarpal (forepaw) and metatarsal or plantar (rear paw) pads provide shock absorption and traction.

Please note that the construction of the rear feet may be smaller than the front feet, depending on the breed.

My reason for this review of the correct composition of the canine foot is that I am concerned about a fault I have noticed in the foot with which I was unfamiliar. Over the past several years, I have noticed when judging that I see more and more dogs in several different breeds (mostly in Golden Retrievers, Australian Shepherds, German Shepherd Dogs, and Standard Poodles) with the toes of their feet pointing upward so that you can see the pads. I first noticed it on the rear feet, and then it started appearing on the front feet as well. This fault needs to be eradicated.

During my research, I have found only two references concerning this abnormality. The first was during conversations with Pat Hastings, who referred me to her book, Structure in Action, The Makings of a Durable Dog, co-authored with Wendy E. Wallace and Erin Ann Rouse. The other comments were found in Canine Form Follows Function, Separating Fact from Fiction by Jeanne Joy Hartnagle-Taylor.

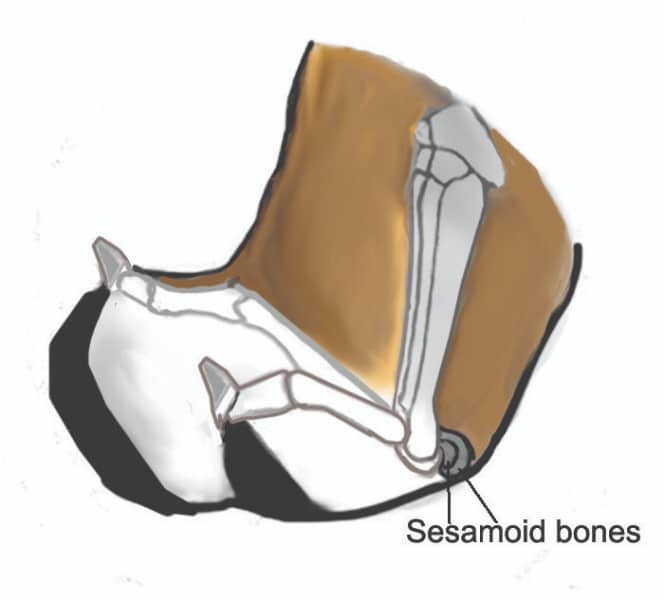

“When the heart-shaped heel or plantar pads are thin and poorly developed, and the ligaments are lax, it allows the heel to roll backward. The four smaller digital pads tip upward, shifting the dog’s weight on the digital sesamoid bones rather than upon the pads. The sesamoids create mechanical leverage and assist with weight-bearing for tendons. Consequently, the dog’s ability to absorb impact and resist tensile and compressive forces produced during muscle contractions is greatly reduced. It also exposes the webbing to injury. This is a severe fault since dogs need sound feet to accomplish their inherited tasks.”

“Rolling Off Pads. Dogs are meant to walk on the pads of their feet and the pads cushion the foot, helping to absorb the concussion of motion. A dog should never roll off of its pads to where the pads show from the front of the foot. However, rolling off pads is becoming a common problem in Golden Retrievers, Samoyeds, Australian Shepherds, and several other breeds. It is caused by connective tissue that is too loose or too long. At one time, we only saw this problem in the rear feet, but now it is also shows in the front feet.”

I have found all of this to be true, especially the fact that it is no longer seen only in the back feet but also in the front feet. This abnormality will eventually cause a breakdown in the metacarpophalangeal joint (Figure 8) at the junction of the #2 phalanx bone and #3 metacarpal bone, where the sesamoid bones (#4) are embedded. It is the same on the rear foot.

“The sesamoid bones are present near freely moving joints. They are usually formed in tendons, but they may be developed in the ligamentous tissue over which tendons pass. They usually possess only one articular surface, which glides on a flat or convex surface. Their chief function is to protect tendons where the greatest friction is developed.”

I hope breeders will pay closer attention to eradicating this fault before it becomes even more entrenched in their breed.

As she was the first one I asked about this abnormality of the canine foot, I cannot help to think of the significant loss to the fancy with the passing of Pat Hastings. Pat was always open to any discussion concerning the dog. If she did not readily know the answer to a question, she would keep looking until she found it. Even if we did not agree on a subject, we were always open to hearing the opinion of the other. I will sorely miss our discussions.

For any questions or comments, please contact me via email: jimanie@welshcorgi.com