Home » The Bedlington Terrier’s Vocation | The Key to Preserving Type

The Bedlington Terrier’s Vocation | Most current judges’ education seminars begin with the words “The [trivet hound] was originally bred for…” thus implying that the breed is no longer used for the purpose for which it was developed. In many instances, this is not the case at all and there are numerous breeds where dogs are hard at work today in the vocation of their ancestors. It’s not about versatility… all dogs are wonderfully versatile. It’s about preserving true breed type through success in the work for which the breed was intended. The truly passionate (and possibly deranged) conformation judge will seek out opportunities to work with, or at least observe working examples of, the breed. As good as our various performance tests are, they cannot simulate the challenges or requirements of actual work.

In days gone by, many breed standards contained a “Scale of Points” which somewhat dictated the relative importance of various structural attributes. This has disappeared from most breed standards, leaving the breeder or judge to set his or her own structural (and temperamental) priorities. Time spent studying a breed at real work will necessarily alter your conformation priorities. Getting some working experience, even briefly, draws your attention to the qualities needed to get the job done. You’ll look at the breed differently if you truly understand what it needs in its toolbox to get the job done.

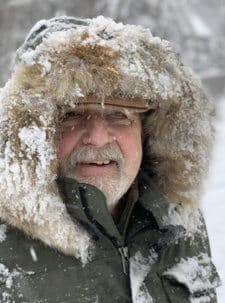

A singular example of this is the Bedlington Terrier. To this day, the “Beddy” is used for hunting in its native UK, the US, and Serbia, to name a few countries. The social media sites for actual working Bedlington have more than 2,000 subscribers, more, in fact, than the conformation sites. It’s a trulyuseful dog for varied quarry around the globe. But the Beddy’s roots are firmly planted in Northumberland where they were developed and where they are often worked today for sport and, in some cases, as a source of income for their owners. If your calendar is too full to get to Northumberland (or even New Jersey where we offer to take judges hunting) I’m hopeful that this article will show you a side of today’s Bedlington Terrier that will assist you in setting your own structural priorities for the breed.

The Bedlington Terrier was specifically designed to hunt the fields and fells of England, and those hills have changed little in the 300-plus years since the breed first emerged. The country is steep, sometimes precipitous and largely open. Today as then, the quarry is largely rabbit (by British law), but in other countries, red and gray fox, groundhog, raccoon, badger (which is legal on the continent), raccoon dog, and wild boar are the current quarry. Even in Britain, fox may be bolted to the gun with the aid of a terrier under certain circumstances.

To understand the Bedlington, one has to understand that the breed is first, foremost, and universally a solo hunting Terrier. It was not developed by Dukes in scarlet on horseback, but rather by laborers, tradesmen, and miners for whom the dog was (and is) an additional source of income. Not all hunting with Beddys was (or… ahem… is) totally within the law. To call the breed a poacher’s dog would be totally disrespectful, but you do need to be aware of some of the breed’s characteristics that make it equally well-qualified for “dancing in the dark” or winning in the show ring.

A barking dog is not an attribute for illegal hunting. Bedlingtons are quiet and dignified… until things get real. They tend to attack without warning, and the strength and ferocity of their grip is legendary. Once attached, they will not release their quarry, which makes them problematic for some types of hunting such as rats, wild boar or the neighbor’s cat. For this reason they are NEVER sparred. Not ever. (Legend has it, though, that after the hunt there were dog fights behind the local pub wherein significant funds changed hands. Just another reason for the

incredible bite.)

Most early Bedlington hunters could only afford to keep a single dog. The breed standard recognizes that constraint by setting a preferred size range, (although it doesn’t specify by whom it is preferred). For a dog to bolt fox from dens in the unforgiving rock of the fells (or the stony fields of New England, for that matter) one wants a smaller dog, 16 inches or less, with the flat-ribbed, deep and compressible chest that enables the Beddy to get into and out of the small dens of the fox andgroundhog. A bigger dog is better-suited as a courser or a lurcher. The very wise folk who developed the breed left you an out: “Only where comparative superiority of a specimen outside these ranges clearly justifies it, should greater latitude be taken.” Big dog/small dog, both have their uses. Relative size should never be the major factor in your decisions.

Along with its overall size, the Bedlington uses lateral flexibility to navigate tight quarters both above and below ground. “Muscular and markedly flexible,” reads the standard. Properly bred, the dog can be neatly folded in half. Often, this is the difference between injury or death and escape from a dangerous situation. Bending the dog is to confirm its flexibility and is standard practice at working terrier shows, but we don’t do it in the conformation ring. Sometimes you can see an indication when it makes its turn on the down and back or when it licks its… well, you know. Not easy to test, but still very important.

The brown hare and its primary predator, the red fox, can achieve speeds up to 48 miles per hour. Both are potential quarry for the Beddy (neither is often hunted with Pugs). For their part, Beddys can achieve speeds upward of 35 miles per hour, BUT, they can sustain that speed for up to three miles. The ability to reach that speed and the endurance to maintain it are the product of a “good natural arch over the loin” and “stifles well angulated.” The arch is moderate; the angulation is not. The arch is nowhere near as pronounced as today’s excellent groomers would like to have you believe. It doesn’t need to be. To be fair, most of today’s dogs actually have a proper degree of arch, which is accentuated by the grooming process. You might want to take a few seconds and peer through that perfect groom to see how much arch is there. Too much of a good thing will have an adverse effect on endurance and spoil the efficiency of the lever action. A roached back and extreme rear angulation will hinder both drive at the trot and the ability to collect its rear at the gallop, actually slowing the dog down.

The AKC and FCI standards both make reference to a “definite tuck up of the underline.” One hopes that the tuck up is not overly pronounced, commensurate with the natural arch, and is the result of superb conditioning rather than the groomer’s artistry.

Many hunting breeds require a tight, round, compact foot. That doesn’t serve the Beddy’s vocation. Instead, we have “Long hare feet with thick, well-closed-up, smooth pads.” Climb and grip rocks, dig to China, sure footing at the gallop. Those long feet are most important almost anywhere the Bedlington hunts. Many Terriers are brought up to the hole and put in to do their work. Not so of the Bedlington who must often cover ground to locate the quarry, then pursue and dispatch it.

We’ve all heard that “Head of Lamb—Heart of Lion” axiom. What you haven’t heard is “The Bite of a Nile Crocodile.” While most hunting dogs find and work their quarry to be dispatched by the gun of the hunter, Beddys, sighthounds (and formerly foxhounds) are often required to bring down their prey. This requires some pretty formidable dentition together with the habit of never (ever) loosening their grip. The key to that punishing bite is “Lower canines clasp the outer surface of the upper gum just in front of the upper canines. Upper premolars and molars lie outside those of the lower jaw.” Any other configuration will have serious consequences to the health of the dog. (Fun fact for conformation judges: Quickly checking placement of the lower canines assures you that there is not a weak underjaw.) This just might be the single most important attribute of the breed.

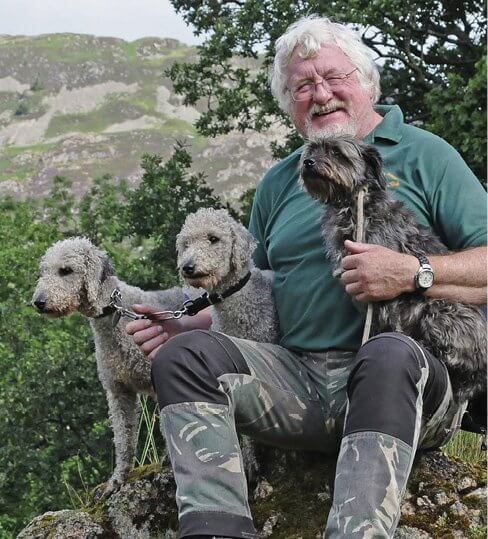

Now if you’re wondering about the tassels on the ears, the exaggerated topknot or the clean-shaven tail, I can only tell you that they’re not much use in hunting. Most Bedlingtons “in work” don’t have these attributes and don’t seem to miss them at all. Still, if you look carefully at the field-bred Bedlingtons, you can see that the conformation standard is as much in evidence in the working hunter as it is in the show champion. Since you, as a judge, have the privilege of setting your own structural priorities, it’s my hope you will consider the most important tools of the Bedlington’s job right up there at the top.

Of course, it’s a dog show, but the best-groomed exhibit may not be the best equipped to do its job. Many of today’s hardest working Bedlingtons are bred from the still-preserved working/conformation lines that made the breed a success. Thanks for helping us preserve the real dog!

The Bedlington Terrier’s Vocation – The Key to Preserving Type

By Richard L. Reynolds